How Photo-Cropping can Change the Narrative

This post is about how a photograph from 1901, showing ‘First Contact’, can be ‘cropped’ by different writers to slant the narrative to suit their own versions of our history. The facts and truth behind the photograph, why it was taken, and in what context, are deliberately overlooked and unacknowledged by these writers, who just want to appropriate the photograph for their own narrow purposes to show non-Aboriginal Australians in a bad light. Very Pascoesque!

1.The Tight Photo-Cropping of Charis Chang in 2019

Published in 2019 by Charis Chang in The Daily Enquirer

Journalist Charis Chang uses this heavily cropped photograph from 1901, under the by-line,

‘WOMEN PREYED ON BY 'ANY AND EVERY WHITE MAN'

in her sensationalist and highly slanted article on,

‘CRIME - Aussie History: Aboriginal women were preyed on’ - The Daily Examiner 27th Jan 2019

Charis Chang, journalist and writer

Ms Chang uses this photograph, with her caption,

‘An Aboriginal woman backs away from a white man holding a gun on Bentinck Island, Queensland in 1901…’ ,

to ‘prep’ the reader for her feminist, anti-colonial diatribe.

Her cropped image suggests a rough, colonial settler, with a gun, and lust in his thoughts, approaching a lone, diminutive and frightened Aboriginal woman and her child, backing away in fear. This sets the sexually exploitative tone of her article, which contains various statements such as :

“…colonisation and the brutal treatment Aboriginal people suffered, maybe it's not so easy to trust authorities that beat, killed and raped them.”

“…the shocking sexual violence that Aboriginal women suffered through.”

“…Aboriginal women were preyed on by any and every white man whose whim it was to have a piece of 'black velvet' wherever and whenever they pleased,"

“Random shootings and massacres of men, women and children were common.”

"These practices, common last century, continued into the first half of (the 1900s) in some parts of Australia…,"

Ms Chang attributes this photograph to the book, ‘North of Capricorn - The Untold Story of Australia’s North’ by Henry Reynolds.

So let us see how faithful Ms Chang has been to her reference source, Henry Reynolds.

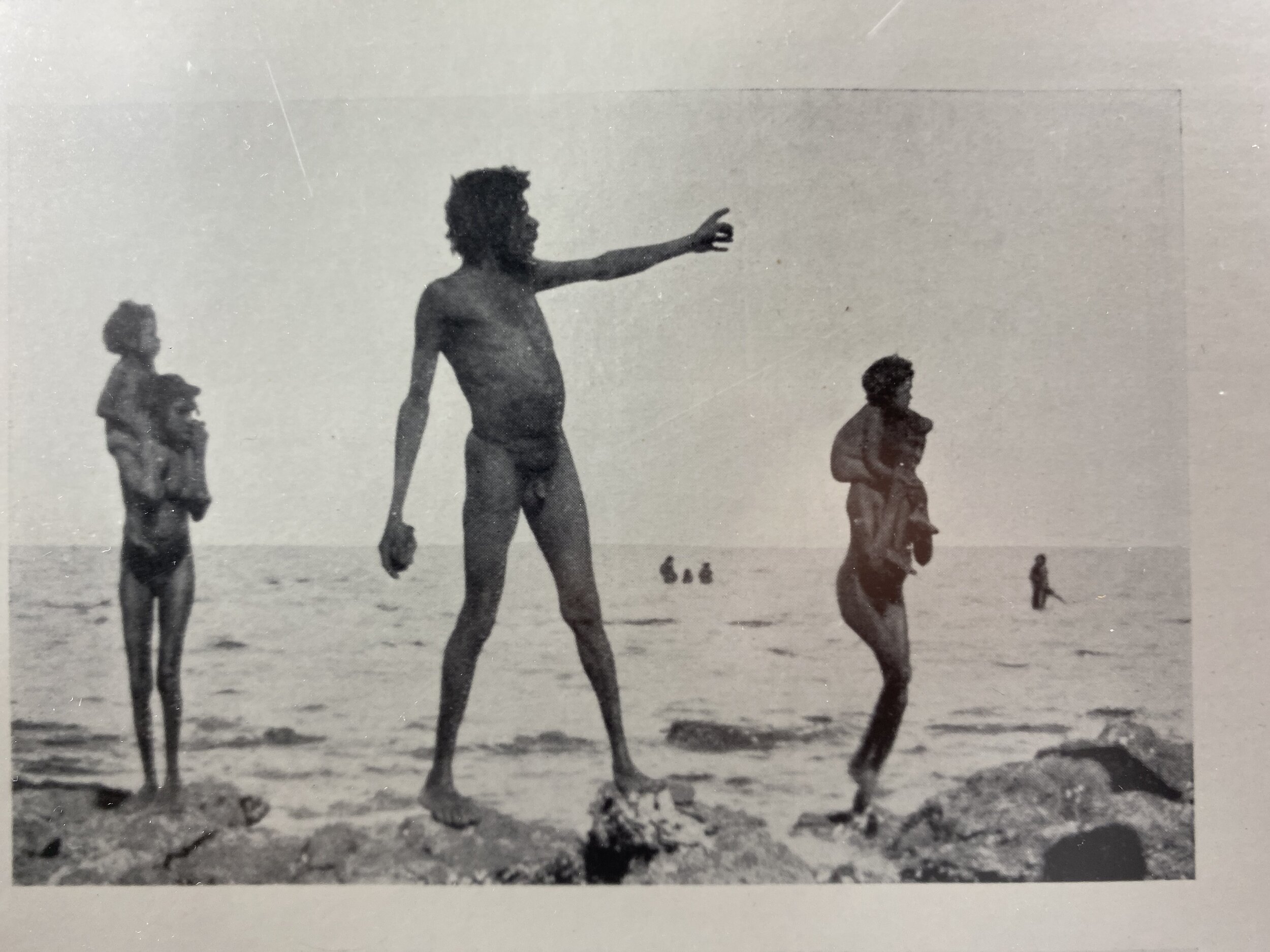

2.Henry Reynolds Opens the Curtain Slightly on his Photo-Cropped Version in 2003

Published in 2003, ‘North of Capricorn - The Untold Story of Australia’s North’ by Henry Reynolds, Allen & Unwin, page 2. No additional reference to the Bentinck Islanders occurs anywhere in Reynolds’ book.

Hmmm, we thinks Ms Chang has been rather selective and misleading. The 2003 image in Henry Reynolds’s book that Charis Chang says she referenced, is more expansive and clearly shows a second Aboriginal woman with her child, who indeed may even be smiling and laughing.

And how does Ms Chang know that the first Aboriginal woman is ‘backing away’? It appears to us that she might even be stepping forward with her right leg and extending her left hand to shake hands with the visitor.

Professor Henry Reynolds

Professor Reynolds’s caption reads :

‘Aborigines, Bentinck Island, 1901. A unique photograph of what may well have been the moment of first contact. The women and children have retreated to the water’s edge. The white man extends one hand in friendship but holds a rifle in the other, hidden behind his leg. - Source : John Oxley Library , 81-4-7 (23176).

So, Professor Reynolds’s caption suggests that the ‘white’ man is endeavouring to extend a, ‘hand in friendship’, but Ms Chang only sees, ‘an Aboriginal woman backing away’ in fear at being ‘preyed on by any and every white man’.

Nevertheless, Professor Reynolds still uses the photograph to hint at some sinister, back-ground motive by the ‘white’ man. The reader still senses that the encounter, however ‘friendly’, may end up being a sexually exploitative and potentially violent encounter between the Aboriginal women and the ‘coloniser’.

But wait - maybe there is more. What is that hint of a shape at the very left edge of the photograph published by Professor Reynolds?

Is the professor also doing some ‘photo-cropping’ of his own?

3.In the Pre-’Black Armband’ World of 1989, Henry Reynolds Shows the Full Photograph

Dispossession, by Henry Reynolds, Allen & Unwin, 1989, p 25.

Moving back in time to 1989, the curtain on this photograph can be drawn wider to the left, revealing more detail as to who was there on the reef, that day in 1901.

In his 1989 book, Dispossession, then Associate Professor Henry Reynolds published the complete photograph, with the caption:

Associate Professor Henry Reynolds

‘There are very few photographs of early contact with the Aborigines. This one is therefore unusually interesting. Taken on Bentinck Island in 1901 it may represent a first meeting at close quarters of white and black. The European extends a hand of friendship but keeps his gun ready for instant use. The women have picked up their children and retreated to the edge of the water. The one closest to the white man looks terrified. The one on the left hides her face in her hands’.

Once again, Henry Reynolds uses this photograph in his book to convey a ‘narrative’ to the reader, but without actually speaking about the Bentinck Islanders anywhere else in the text of his book.

He uses this as a photograph of a ‘white man' at First Contact extending ‘a hand of friendship’, but ‘keep[ing] his gun ready for instant use.’

Furthermore he says,

‘The women have picked up their children and retreated to the edge of the water. The one closest to the white man looks terrified. The one on the left hides her face in her hands’.

Maybe, maybe not. Reynolds doesn’t comment on the woman in the centre, who seems to smiling or even laughing. And what does, ‘hides her face in her hands mean?’ Maybe at the decisive moment she is waving flies away? Maybe she is just shy? Maybe she was scared of the camera?

And how does he know they have retreated to the waters edge? Maybe they emerged from the water to meet the visitors? In the far background one can see another member of the tribe who has not emerged from water, but stays far out on the reef away from the visitors.

But more importantly, what is the woman on the far left looking at? She is not looking at the ‘white man’, but instead is focused on something out of the frame, on the far left.

Associate Professor Reynolds hasn’t given the reader any real detail or context for this photograph. He just uses it to support the narrative, in his book Dispossession, of the violent dispossession of Aboriginal people and their ‘brutal conquest’.

4.First Contact with the Kiaidilt in the 20th Century Leading to Their Eventual Rescue & ‘Coming-In’

Two of Roth’s party on the edge of reef. The Kaiadilt man on the right is Kalturingati walta, as identified by his son…Mrs. R.H. Wilson’s copy of this picture is labelled “Bentinck Island, June 1901”. Photo: J.F. Bailey; original negative in South Australian Museum - from Tindale, N. 1962

Kaiadilt men on the edge of the reef; in the background one is holding up a mass of debris. Central figure is Tarukingati warungalta, as identified by his son. Photo: J.F. Bailey 1901 - from Tindale, N. 1962

A group of timorous Bentinck Islanders as seen by W. Roth in 1901. The central Kaiadilt man is holding a tjilanganda or mariwu (crude biface stone implement) in his hand. Photo: J.F. Bailey 1901 - from Tindale, N. 1962

We have found some other photographs, taken at exactly the same time and place on Bentinck Island, as the photograph used and ‘cropped’ by Ms Chang and Professor Reynolds, which put their photograph into context.

Ms Chang and Professor Reynolds have ‘cropped’ their photograph to convey their narratives that our colonial history was nothing other than a clash between gun-totting, sexually aggressive ‘white’ men and fearful and exploited Aboriginal women.

Neither Ms Chang nor Professor Reynolds refer to the Aboriginal people in the photographs by their names, or even their tribal name, the Kiaidilt. They merely appropriate a photograph of some ‘Aboriginal women’ at First Contact and crop it to varying degrees to convey their version of a violent, sexually exploitative history of Australia.

The fact of the matter is that a series of photographs was taken in 1901 by an expedition to Bentinck Island, lead by Dr Walter Roth, Protector of Aborigines for North Queensland. He was accompanied by a party of Native Police, J. F. Bailey Director of the Botanic Gardens in Brisbane and Charles Hedley, a zoologist. Guns were carried by the expedition for security reasons, given that the Kiaidilt were known to be engaged in fearful inter-tribal spearings.

Nevertheless, the full set of photographs show scenes of an apparent friendly interaction.

Although ‘timorous’, the Aboriginal women that Ms Chang and Professor Reynolds say show, ‘fear’, ‘terror’ or ‘are hiding their face with their hands’, now look to be voluntarily engaging with their visitors. One of Roth’s party, holding his gun in clear view, appears to be playing with a woman’s child - this woman appears to be the one that Professor Reynolds says, ‘was hiding her face’.

And the gun-toting, potential ‘rapist of a whiteman’ in Ms Chang’s photograph, appears at the right-edge of the frame, in close and friendly proximity to the Aboriginal men, who are presumably the husbands of the women in the photographs. But in Ms Chang’s twisted, radical feminist world, where ‘all men are rapists’, the fact that he appears to be smoking she might perhaps claim as, ‘post-coitus’ evidence! Perhaps he really was the ‘white’ Colonial rapist, as Ms Chang would have us believe, and he did his foul deed when the photographer was not looking and now quietly enjoys a cigarette?

Ultimately, the majority of Kiaidilt ‘came-in’ during the late 1940’s due to the effects of a severe drought, inter-tribal fighting, disease and malnutrition, the combination of which threatened to wipe out the population. A massive tidal wave in 1948 forced the evacuation of the last of the Kiaidilt remaining on Bentinck Island to nearby Mornington Island, where they have remained ever since.

This is an example once again that Australia’s Colonial and Post-Federation Aboriginal history is not just about dispossession and massacres. There are many examples where Aboriginal people expressed their agency and decided to ‘come-in’ to join Australian society, to varying degrees, to suit themselves.

The moral to this story is that Australia’s history is nuanced, and behind every photograph put forward by the the Post-modern history revisionists, there is often another, more positive story.

That is not to claim that there were not indeed many appalling incidents of killings, massacres and rapes, predominantly against Aboriginal people by the settlers, but these incidents were not condoned officially by Government policy. The Authorities did their best to reduce the incidence, and severity, of any violence and severely punished transgressors. To always show non-Aboriginal Australians in such a negative light is plainly wrong. When presented with an ‘anti-colonial narrative’, readers need to be cautious and be willing to question and apply critical thinking as required.

References

Tindale, N.,- 1962 : Geographical Knowledge and some Population Changes of the Kaiadilt People of Bentinck Island, Queensland, Records of the South Australian Museum, VOL. XIV No 2. July 27th 1962

Below are the images in a larger format

Bentinck Island group, photographed on Roth Expedition 1901, from Graham-Stewart, M., Bitter Fruit -Australian Photographs to 1963, 2017