Has Henry Reynolds signed on as the latest 'Sorcerer's Apprentice' to learn some 'creative writing' skills?

From our research in a previous blog-post, we did discover that historian Henry Reynolds appeared to be quite willing to misleadingly photo-crop an image to suit a particular, anti-colonial narrative, see here.

However, in following his long career, we did at least think that he maintained a level of professionalism by accurately quoting from good quality primary and secondary sources, when he cited them in his works. But now we are not so sure.

This realisation is a big disappointment to amateurs like us at Dark Emu Exposed, as we always thought that this multi-award winning historian, and former Associate Professor, was properly trained and educated ‘in the art of historiography.’ We thought his ability to delve deep into the primary archives and locate and determine the facts, then sift the evidence, was reliable, even impeccable. Although, we might not agree with his final interpretations and conclusions, at least we needn’t have any doubts about the veracity of the facts and evidence he presented to us. Or so we thought.

In his recently published book, Truth-Telling - History Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement however, he refers to the discredited book, Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe, as if it is a credible source (ibid., p54).

More worryingly, he appears also to have adopted some of Bruce Pascoe’s ‘selective editing’ techniques, which greatly diminish his professional standing, in our opinion.

Has Henry Reynolds been influenced by the ‘sorcery’ of Bruce Pascoe’s, best-selling, history re-writing skills? Is Henry Reynolds now engaging in a little, ‘invention of a false past’ himself by adopting some ‘selective quoting’ and ‘out of context’ historiography?

We indeed think so, and to illustrate our point, consider the following examples.

1.- The ‘Secret Instructions Conspiracy’

To our mind, Henry Reynolds is a purveyor of what we call, ‘The Secret Instructions Conspiracy’, which aims to convince Australians that,

‘If only Captain Cook had just done his bloody job properly and followed the Secret Instructions given to him by the British Admiralty, then Aboriginal people would be in a much better position today, possibly in charge of their own Sovereign Nation(s) with lucrative, rent-paying Treaties with the Commonwealth government and/or one or more of the State governments’.

In his book,Truth-Telling, Henry Reynolds in our opinion, misleads his readers by giving further life to this viral idea pathogen that Cook failed to follow his Secret Instructions, when he writes,

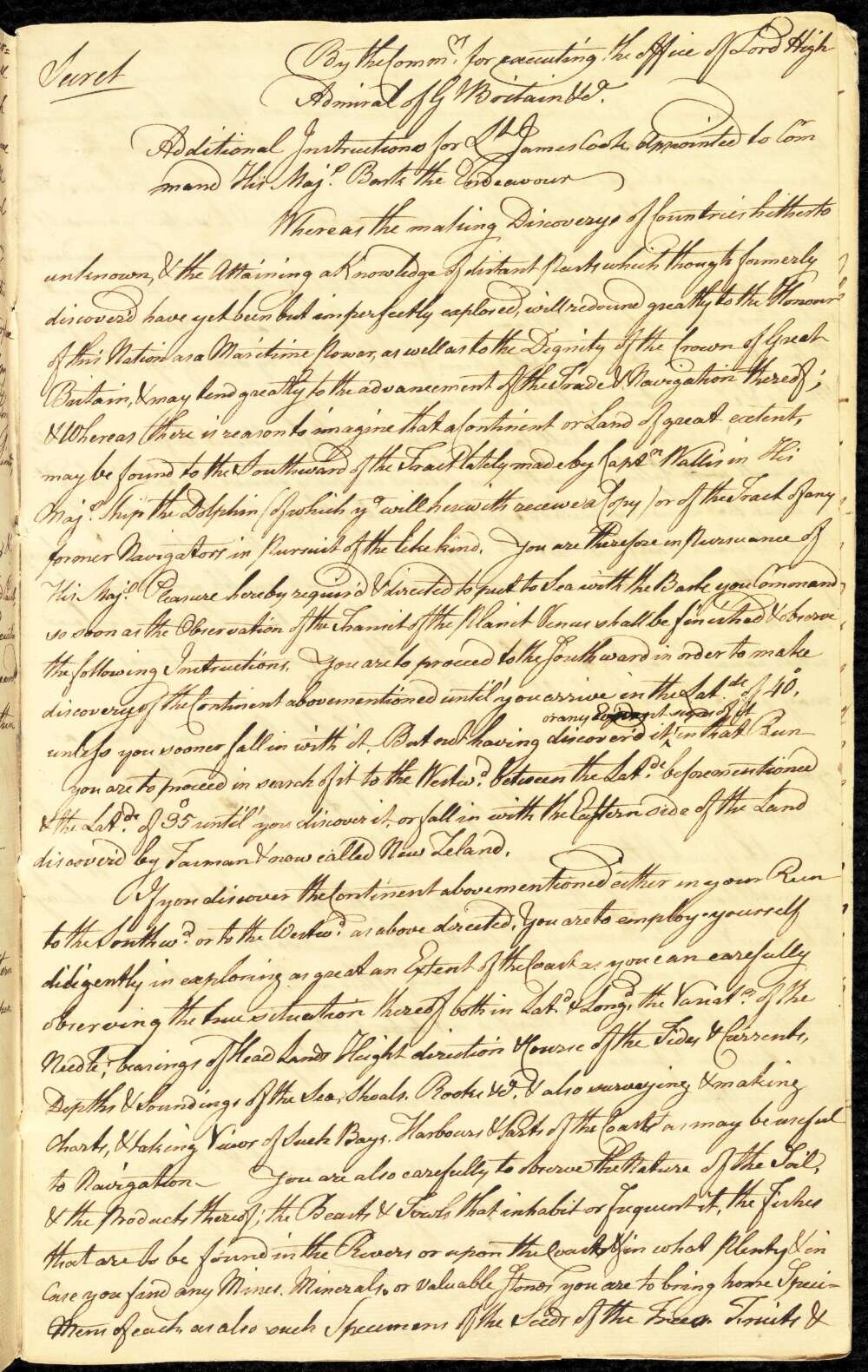

Fig. 1 - Cooks Secret Instructions of 30th of July 1768 for the Endeavour’s Voyage. - Scan Source

Fig. 2 - Read Transcript here with relevant text highlights

Source : Foundingdocs.gov.au

This brings us to an even more contested question. Did Cook's claim of possession [of the east coast of Australia] dispossess the resident Indigenous nations? Many commentators have believed that it did. Cook's secret instructions of 30 July 1768 are frequently referred to. They included the following injunction:

‘You are also with the consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the name of the King of Great Britain; or, if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for His Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.'

The two parts of these instructions are quite different. Many commentators have argued that Cook wilfully disobeyed the injunction to gain the consent of the natives. But he nowhere attempted to take possession of convenient situations with an eye on future settlement, which was not being considered at the time.

But the second part of the instructions opens up an array of problems. Did Cook wilfully behave as though eastern Australia was uninhabited when he knew full well that it wasn't? If so, it was a serious dereliction of duty with little basis in either international law at the time or widely accepted morality. - (ibid., p15 here) - [our emphasis].

We were at first stunned on realising that the famous historian Henry Reynolds was using Bruce Pascoe’s technique of ‘selective quoting’ from Cook’s Secret Instructions to push the narrative onto the reader that Cook was guilty of a dereliction of duty - a serious dereliction of duty if he wilfully behaved as though eastern Australia was ‘uninhabited’, or presumably, a casual dereliction of duty if he unthinkingly behaved as though eastern Australia was ‘uninhabited’.

Just pause for moment and consider what Reynolds, a man comfortably ensconced in his metropolitan armchair in 2021, is accusing the legendary James Cook of - an eighteenth century man of duty who went to sea as a teenager, who served the British Admiralty with dedication, distinction and fame, in war and exploration, until his murder while on duty, and who was roundly praised by all in the way he treated his seaman and carried out his scientific voyages.

Yes, Reynolds wants to lead his readers into believing that here was a man guilty of a dereliction of duty and of dubious morals!

Then it dawned on us that maybe Henry Reynolds had done us, ‘average’ Australians, a favour. In the past, when an academic wrote a book, we ‘amateur history buffs,’ just read it and generally believed what we read because, well, it was written by a professional academic historian, who had spent years studying his craft and subject, so it must be true.

But now, when we read something that doesn’t look quite right, or if we are being told by ‘an expert’ to radically alter our understanding of our Australian history due to new ‘evidence’ (Note 1), we can just ‘go onto the internet’ and check the veracity of what is being foisted onto us.

So, let’s ‘goggle it’, and see if the highly acclaimed historian, Henry Reynolds is being totally straight with his readership.

The first thing we notice about Reynolds’ quote from Cook’s Secret Instructions is that he doesn’t seem to have gone to the primary source. Instead, he cites a secondary source, The Explorations of Captain James Cook, by A G Price (Angus & Robertson, 1958, p.19). We however, have gone to The Museum of Australian Democracy to download a photographic scan of the original hand-written instructions (see Fig. 1 above) and an official transcript (see Fig. 2). We have highlighted in yellow a number of the relevant passages in this transcript.

The reader will see firstly, that,

the Secret Instructions do not even mention New Holland, or its east coast; and

secondly, they are almost wholly concerned with instructing Cook to sail south after his observations of Venus (in Tahiti) and then eastwards, to New Zealand, in search of the fabled 'Great Southern Continent.’

Indeed, on the second page the Secret Instructions are explicit,

‘…the Object which you are always to have in View, the Discovery of the Southern Continent so often Mentioned’.

In the event that Cook found the Continent, he should chart its coasts, obtain information about its people, cultivate their friendship and alliance, and annex any convenient trading posts in the King's name. He was instructed to,

‘…with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the name of the King of Great Britain:’

or, if he found,

‘the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.’

These Secret Instructions are clearly referring to ‘the Country’ in question, that is, the ‘Southern Continent so often Mentioned’, the Great South Land, and they stop at New Zealand. They do not mention New Holland, or even ‘those portions of the coast-line of New Holland which had not been visited by the Dutch’ (Note 3). One of the most exciting exploration quests in Europe at that time was to be the first to discover the ‘often mentioned’ Southern Continent and that is probably why these instructions were ‘secret’ (Note 6). Britain did not want any other country, especially France, get wind of what Cook was really up to.

So it is totally misleading for Henry Reynolds to selectively quote from these Secret Instructions and conflate the specific instructions to Cook to take possession of the ‘Country’ (that is, the mythical ‘Southern Continent’) with the ‘consent of the natives’, with how Cook could take possession of other islands and lands that he might discover before he entered, or after he left, the search zone for the Southern Continent. Tellingly, the Secret Instructions specifically DO NOT tell Cook to obtain the ‘consent of the natives’ when he discovers and takes possession of ‘other’ islands, viz:

‘You will also observe with accuracy the Situation of such Islands as you may discover in the Course of your Voyage that have not hitherto been discover’d by any Europeans and take Possession for His Majesty.’

The east coast of New Holland falls into this category, and so Cook had no specific Secret Instructions regarding the obtaining of the ‘Consent of the Natives’ of the east coast of New Holland, prior to his taking possession. As the commander on the spot, he was authorised to exercise his duty as he saw fit to make decisions according to the Admiralty’s orders, and his understanding of International law and the morality of the times, which he did.

He did not formerly ‘take possession of New South Wales ‘with the Consent of the Natives’ because,

his instructions did not tell him to;

the Aborigines either failed to offer, or engage in, any treaty negotiations (the American Indians did);

the Aborigines failed to send a delegation of their chiefs, or invited the British into their ‘settlements’, to negotiate; (the Maori did);

the Aborigines failed to send any of their people voluntarily with Cook to meet the King (the Tahitians did);

the Aborigines did not live in permanent settlements, ‘cultivate the soil’ or show any signs of a ‘government’ (like the Maori did; and see Mabo’s (a cultivator) legal success; and the French attitude when colonising New Caledonia in 1853, as being the same as the British);

the Aborigines had no desire for any of the goods that Cook offered them - they simply looked at the gifts given to them and then discarded them. There was nothing of interest to the Aborigines that the British could offer under a Treaty in exchange for land or trading posts, and

the natives often totally ignored the presence of the British, or just ran away at the sight of the British visitors (Note 2).

What was Captain Cook to do?

Cook understood that his duty and moral obligations required him to chart as far as practicable the east coast of New Holland and, in the absence of finding a local sovereign power, or natives that had a civil polity that was capable of negotiating their consent, he was to claim the land for his Majesty as first discoverer and possessor.

To expect Cook to have done anything differently, under the circumstances in which he found himself and the Aborigines, is an impossibly unrealistic expectation.

Is Henry Reynolds saying that Cook was ‘derelict in his duty’ and ‘immoral’ because he failed to look 250 years into the future and comprehend that some Aboriginal people in 2021 would feel political justice was denied them, that day in 1770 on Possession Island, when Cook claimed the land for the King without their Aboriginal ancestors formal consent?

Is Henry Reynolds telling us that our society today is derelict in its duty and morals because we can’t see 250 years into the future to make sure we don’t pass laws today that some group in the year 2271 might feel has denied them justice?

What a ridiculous idea to blame Cook for the failings of some modern day Aboriginal people, who claim that they lack the political justice they deserve in 2021.

Fig 3. Some Aboriginal people present their Barunga Statement (Treaty proposal) to Prime Minister Bob Hawke in 1988. Why didn’t they do it in 1770 or 1788?

If we elaborate on Henry Reynolds’ thought bubble, we could just as easily say Aboriginal people were derelict in their duty in taking 200 years to get their act together in developing their claims for a Treaty, such as they finally did with their Barunga Statement of 1988.

Why did they present the Barunga Statement to Prime Minister Bob Hawke?

Why didn’t they present it to Captain Cook at the get go? Cook would have undoubtably seen this as a Treaty negotiation from an Aboriginal polity that was capable of negotiating, and he would have acted accordingly to negotiate a Treaty to cede some, or all, of the territory, before taking possession.

Using the finger-pointing reasoning of Henry Reynolds, why weren’t the Aboriginal Elders of 1770 guilty of a dereliction of their duty to their people by not looking into the future and realising that they needed to step up and take responsibility and negotiate a treaty with Cookie asap?

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars But in ourselves, that we are underlings.”

(Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene III, L. 140-141)

2.- The ‘Captain Cook Acted Immorally by Taking Possession’ Conspiracy

Henry Reynolds asks us in his book, Truth-Telling,

Did Cook wilfully behave as though eastern Australia was uninhabited when he knew full well that it wasn't? If so, it was a serious dereliction of duty with little basis in either international law at the time or widely accepted morality. The most pertinent illustration of contemporary standards can be found in the material presented to him by James Douglas, the 14th Earl of Morton, on behalf of the Royal Society, which had sponsored the voyage into the southern seas. Writing about the Indigenous people that the voyagers would encounter, Morton observed that they should be seen as ‘the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit' and that even conquest of 'such a people can give no just title'. - (ibid., p.15-16)

Here is another prime example of Henry Reynolds using the Pascoesque technique of ‘selective quoting’ to ‘slant the narrative’ so that gullible readers might easily be convinced that Cook ignored the ‘correct’ contemporary legal and moral advice, given by an aristocratic ‘sponsor’ of his voyage no less, when it came to dealing with the Aborigines. We also think that there a case to answer for by Henry Reynolds who, like Bruce Pascoe, appears to be ‘just making stuff up’ in some of his claims, as we will allege in our Example 3 below.

Reynolds wheels in this aristocrat (Note 4), the 14th Earl of Morton, as being a ‘pertinent illustration of contemporary standards’ of eighteenth century British legal and moral values, with regard to dealing with ‘natives’ in newly discovered lands.

The Earl is someone who, Reynolds seems to imply, should be listened to – he is authoritative and represents the ‘sponsor’ of Cook’s voyage, and his legal and moral views with regard to natives in newly discovered lands are of the highest contemporary standard. Or are they?

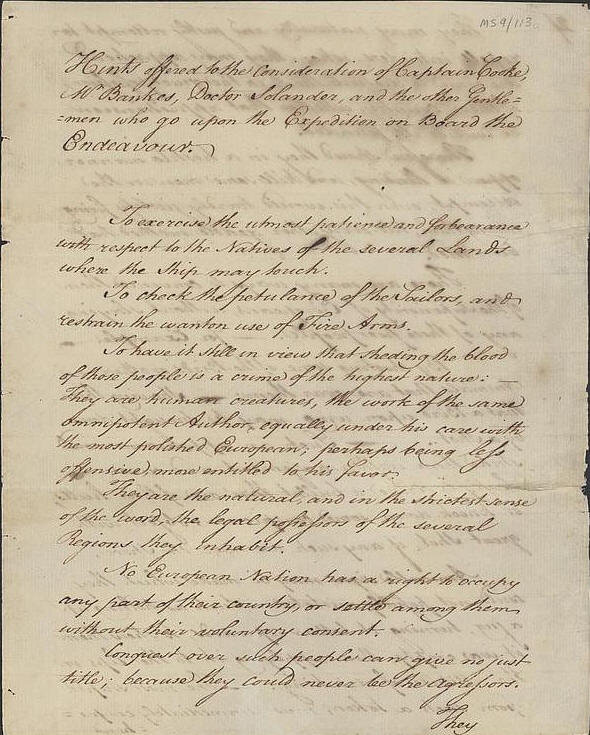

Reynolds only gives us two short snippets of ‘the material presented to him [Cook] by James Douglas, the 14th Earl of Morton, on behalf of the Royal Society’. We have tracked down the complete ‘material’, which we note, includes the following interesting points.

Rather than being ‘presented to Cook as being authoritative, it is described as being merely ‘hints’ and ends with a final paragraph that admits its content are ‘probably very incorrect’! Reynolds’ important ‘material’, just looks like one of those self-deprecating, timid emails newspaper editors of today get on a daily basis from well-meaning readers, offering mostly impractical or hackneyed advice!

Hints offered to the consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr Bankes, Doctor Solander, and the other Gentlemen who go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour…

… The foregoing hints, hastily put together; and probably very incorrect, are however humbly submitted to the consideration of Captain Cooke and the other Gentlemen,

by their hearty wellwisher and Most obedt Servant

MORTON Chiswick wednesday 7 I0th August I768.

[our emphasis. Full transcript with our highlights here from Beaglehole, J.C, (Ed.) The Journals of Captain James Cook, Vol I, 1955, Appendix II, p514-519]

[‘hints’ - noun, an indirect or covert suggestion or implication; a brief, helpful suggestion; a piece of advice; a very small or barely perceptible amount- Macquarie dictionary.]

Fig 4. Image of a page of Earl of Morton’s ‘hints’ to Captain Cook for his voyage on the Endeavour. Source : The Douglas Archives

So, Reynolds would have us believe that the ever professional Cook, whose direct line of command was to the British Admiralty and not to the Earl of Morton, was potentially guilting of,

‘a serious dereliction of duty’

because, Reynolds asserts, he failed to adequately take into account the hastily cobbled-together handwritten ‘hints’ of the aristocratic Earl?

A naval Captain could be court-martialled for a dereliction of duty that involved disobeying his commander’s direct order or written instructions. Is Henry Reynolds seriously expecting us to accept that the same would apply if a naval Captain failed to comply with a list of hints given to him by some well-wisher, who wasn’t even in the Navy?

Give us a break Henry!

One of the most disrespectful, and dangerous, aspects of the re-writing of our history by revisionist authors such as Bruce Pascoe and Henry Reynolds is their denunciation of our historical figures as,‘if they are living figures responsible for the many ills inflicted on the world today’ (Note 5).

In 2000, Professor Henry Reynolds presented a paper at a National Library of Australia conference, in which he said,

‘Historians are called upon to play a forensic role of uncovering and proclaiming the truth. Society expects much of them—at the very time that they are consumed by epistemological doubt and are not sure if they can find out what actually happened in the past. The irony was not lost on the American legal scholar, Mark Osiel, who wrote…

"Before there is any debate about who is morally or legally responsible for what, about which lessons must be learnt by whom to prevent the catastrophe’s recurrence, people want to know ‘the facts’.

It seems we at Dark Emu Exposed and Henry Reynolds with his newly published book, Truth-Telling, can’t agree on the facts and how morally and legally responsible Captain Cook is for the supposed ills of today’s Aboriginal Sovereignty activists.

So, let’s play a mind game.

Rather than take our emotions back 250 years to Cook’s time to argue about how concerned, and morally and legally bound, modern Australians should be due to what Cook did in 1770, let’s bring Cook himself and his actions forward into our time and put his spirit into our shoes and see how we would act under his ideas of duty, morals and laws. Let’s not judge Cook’s time with our eyes, let’s use Cook’s eyes to judge our times.

Would we make decisions that are dutiful, just, moral and capable of withstanding the judgement of our descendants 250 years into the future?

The mind game opens with,

It is July 19th 2013 and Captain Henry Reynolds*, commander of an Australian Navy frigate based in Darwin, is reciting to his crew the Acknowledgement to the Larrakia peoples and their Land and Waters, before heading out on humanitarian work rescuing overcrowded, and often sinking, refugee boats. These boats are entering into Australian waters from Indonesia and, for Captain Reynolds and his crew, it is a hectic time with an explosion in the numbers of refugees now coming and having to be rescued. Distressingly over the last month alone, Captain Reynolds and his crew have pulled dozens of the decaying bodies of dead refugees - men, women and children - from the sea, tragically drowned while trying to reach Australia.

Captain Reynolds usually finds some solace from the horrors of his job by reading before bed, the Journals of James Cook. But on this night he cannot concentrate because tommorrow he knows he will have some difficult choices to make. The discharge of his duties, his moral integrity and his ability to comply with International Law will be brought into question. For today, he has been informed that Prime Minister Rudd has announced a radical change to the refugee program, with the announcement that no refugees will be brought to Australia, but they instead will be sent to a third world country for processing and will never be settled in Australia.

Being a member of the Navy, Captain Reynolds knows that he is under duty to follow the orders, that will most surely flow down the chain of command, to ‘stop the boats’ or rescue the refugees from their sinking craft and take them by force, for surely they will not consent and may violently resist, to Port Moresby for ‘offshore processing'. Reynolds must uphold his duty to his crew and his commander and comply with all the confidential, secret instructions he will receive.

Also by his bedside, Captain Reynolds keeps a copy of ‘hints’ present to him by a friend, a Catholic bishop, who is rather an aristocratic sort of fellow Reynolds always thought, but well-meaning in his advice nevertheless. These ‘hints’ tell Reynolds that he is must, ‘with the consent of the refugees’ take them to the country that they wish to call home. They must be allowed to enter Australia. Captain Reynolds knows that in our times, this is a ‘widely accepted morality’ and some have even accused Australia of Torture in the United Nations. But Reynolds also knows that Australia, the country he swore an oath to serve, has an Internationally accepted, legal basis for claiming, ‘we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come’.

Captain Reynolds is torn between what to do. Will he do his duty to the Navy and the Commonwealth Government of Australia, who will require him to transport the refugees to PNG against their will, and risk that, in 250 years time, the descendants of these Afghan refugees, displaced by the war in Afghanistan, of which Australia was a part, will sue the Australian government for Inter-generational Torture and Human Rights Abuse? Or does he risk a charge of a serious dereliction of duty by upholding the ‘hints’ of the Bishops, the holders of our society’s ‘contemporary standards’ and hence, surely be court martialled for refusing to allow his ship to be used in the ‘offshore processing’ program?

Captain Reynolds reaches for his copy of the Endeavour’s Journal - what would Captain Cook do, he thinks?

Indeed, what would any of us do, Henry?

Man is neither angel nor brute, and the unfortunate thing is that he who would act the angel acts the brute.

- Montaigne, Of Experience, quoted from The Western Canon, H. Bloom, p.150

* - Not his real name

3. Is Henry Reynolds, like Bruce Pascoe, ‘Just Making Stuff Up’ ?

Henry Reynolds asks us in his book, Truth-Telling,

Did Cook wilfully behave as though eastern Australia was uninhabited when he knew full well that it wasn't? If so, it was a serious dereliction of duty with little basis in either international law at the time or widely accepted morality. The most pertinent illustration of contemporary standards can be found in the material presented to him by James Douglas, the 14th Earl of Morton, on behalf of the Royal Society, which had sponsored the voyage into the southern seas. - (ibid., p.15-16) [our emphasis].

Did they? Is Henry Reynolds correct in saying that the Royal Society sponsored Cook’s voyage in the Endeavour?

Or is Henry Reynolds ‘just making this up’, a la Pascoe, so as to add further weight in the readers eyes that here was that ‘rogue’ Cooky, taking the funds for his voyage from the highly moral Earl and the Royal Society, without any intention of adhering to the Royal Societies ‘hints’ as discussed above. What a dereliction of duty we hear Henry cry!

Well the grannies and grandads at Dark Emu Exposed have done some digging and we suspect that Henry Reynolds is just plain wrong. It doesn’t look like to us that the Royal Society coughed up the funds to financially ‘sponsor’ the Endeavour’s voyage at all. The references to the pertinent documents that we have uncovered show that the Royal Society was 'crying poor’, and so the King (and ultimately the poor taxpayer we suspect?) graciously granted the 4000 pounds requested by the Royal Society for their scientific expedition plus the cost of the ship which the Admiralty funded. All Cook ever got from the Royal Society it seems, was 120 pounds for the extra work he did as one of the Observers on the voyage.

We will let the reader decide, if Henry Reynolds is correct in saying that the Royal Society sponsored Cook’s voyage, by examining the relevant excerpts we have recovered from the ‘Calendar of Documents’ available in Beaglehole, J.C., The Journals of Captain James Cook, Hakluyt Soc., CUP, Vol 1, 1968, Appendix VI 602ff.

The Royal Society cries poor and requests funds, which it receives from the King - here

Relevant Minutes of the Royal Society explaining the same and appointing Cook as an Observer - here

The Admiralty pays for the Endeavour and its fit-out, and Cook dips into his own pocket for expenses that are reimbursed by the Admiralty (not the Royal Society) - here

Notes & Further Reading

Note 1 : “So while the [Uluru] Statement from the Heart urges Australia to come to terms with a radical new version of the nation’s history, it throws up an even more challenging interpretation of the law and in particular our understanding of the imposing question of sovereignty.” - Henry Reynolds, Truth-Telling (ibid., p.3).

Note 2 : “…as we approached the shore they [the Natives] all made off and left us in peacable posession [sic] of… the island…”

From Cook’s journal record of the landing on Possession Island, off the tip of Cape York, where the locals fled rather than stick around to negotiate a Treaty prior to Cook raising the flag and taking possession as first discoverers. See Beaglehole, J.C., The Journals of Captain James Cook, Hakluyt Soc., CUP, Vol 1, 1968, p387 below.

Note 3: Barton, G.B. History of NSW from the Records, Sydney, Charles Potter, Government Printer, 1889, Vol 1, pp. 177-178, cited from Note 6 below.

Note 4 : Reynolds uses an old writing technique to ‘slant the narrative’, when describing the views of his characters.

A ‘good guy’, with the right views he introduces as, ‘James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton’;

that is, in typical and likeable Aussie fashion - non-formal name first, followed by his title, which is required to place him in the historical context.

Compare this to how Reynolds describes one of the ‘bad guys’ in his book, only four pages later :

‘…the aristocratic president of the Royal Society, Joseph Banks…’;

that is, in a way to denigrate Banks’ standing amongst Reynolds’ egalitarian and sneering anti-Royal, republican Aussies.

Never mind the fact that Douglas, as an Earl, was an aristocrat with a peerage, and of a very much higher rank than the landed gentry man, Joseph Banks Esq as he was during the time of Cook’s 1770 voyage of discovery.

Joseph Banks ‘was still styled “Joseph Banks Esq” when elected President to the Royal Society in November 1778. A couple of years later, believing the office deserved a higher rank, he took discrete steps to be entered on the Roll of Baronets. His wish was granted and, on 23 March 1781, after attending the King’s Friday levee, he emerged from St James’s Palace as Sir Joseph banks, the first and only Baronet of Revesby Abby in Lincolnshire’ (Note 8). Compared to the James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, Sir Joseph Banks had the relatively lowly, and non-peerage, title of Baronet.

Never mind the fact that both Douglas and Banks were ‘presidents of the Royal Society’, at the times relevant to when Reynolds cites them in his book.

- La plus belle des ruses du diable est de vous persuader qu'il n'existe pas.

(The devil's finest trick is to persuade you that he does not exist)

― Charles Baudelaire, Paris Spleen

Note 5 : A timely and insightful article on this topic appeared this week by Frank Furedi, in The Australian, Feb 13-14, 2021, from which we will borrow.

Note 6 : The British Admiralty appears to have been ‘paranoid’ about secrecy with regard to Cook’s voyage, specifically issuing an order to all ‘The Flag Officers, Captains and Commanders of his Majesty’s Ships and Vessels to whom this shall be exhibited.’ (see here)

Nevertheless, according to author, Margaret Cameron-Ash in her excellent book, ‘Lying for the Admiralty’, one wonders how secret they may have been when she writes,

‘Although these instructions were marked ‘secret’, they were largely reported in the London newspapers before Cook sailed.’ (ibid., p10)

[Ed Note: this book by Cameron-Ash is very worth buying as it provides credible answers to many of those questions that many Australians must have asked themselves over the years such as, ‘If Captain Cook was so good, why did he just land and describe Botany Bay, which is a complete ‘dud’ compared to the ‘finest harbour in the southern hemisphere’ a few klicks north? How could he miss Sydney Harbour so completely? (actually he didn’t, so read the book!). [Ditto his ‘botched’ charts for the entrance to Bass Strait, the Stewart Peninsula/Island in New Zealand, as well as other credible revelations.]

Note 7: The Trap of Accepting Critical Race Theory and Identity Politics as Being Valid.

Having an argument about whether Australia should have formal, so called, ‘Aboriginal Treaties’ and/or ‘Aboriginal Sovereignty’ is largely academic. The reality is that Aboriginal people already have Sovereignty, as Australians. They have an equal share of the United Nations recognised, Sovereign Nation of the Commonwealth of Australia. Australians who want to identify as Aboriginal are not discriminated against : they have full citizenship and voting rights; they can apply for an Australian passport; they can freely personalise their lifestyle to live anywhere on the spectrum, from a small community on Native Title lands with their ancient customs in remote Australia, right up to being fully integrated into our pluralist Australian society by living in the towns and cities of regional and metropolitan Australia.

Just because certain intellectuals and Aboriginal Political Elites bang-on about the historic injustices of a group of people identified by the colour of their skin or genetic history or ‘race’, who they say need ‘recognition’ as being ‘separate’, ‘special’, ‘oppressed’ and in need of costly Social Justice remedies or their own sovereignty, doesn’t mean the rest of us have to believe them.

Australians recognise that in our society today there are still problems that need to be fixed for some of our citizens and the reality is that we have been fixing them steadily, year by year, over the past 250 years. There is no need for Australia to engage on equal terms with a ‘racist’ ideology that seeks to undermine our wonderful Australian society by continually ‘inventing false pasts.’ Just flick through Henry’s new book and then consign it to the dustbin of activist history along with the others.

Note 8: Margaret Cameron-Ash in Beating France to Botany Bay, by Quadrant Books, 2021, p74, quoting Carter, H.B., Sir Joseph Banks, 1743-1820, (1988) p 176