The Re-Imagining of Moreland

Introduction and Proposal

This post is about the 3 July 2022 decision by Moreland City Council to change the municipality’s name from “Moreland” to “Merri-bek”.

This decision was made because in November 2021 information was presented to Council by Elders from the Aboriginal Traditional Owner community and other community representatives, which allegedly showed that the name “Moreland” was derived from the name of a Jamaican slave estate allegedly operated by the ancestors of Dr Farquhar McCrae who settled in our municipality in 1839.

To verify these allegations, Council commissioned a report on the name “Moreland” by Dr James Lesh of Deakin University.

Dr Lesh presented his findings in April 2022 with the conclusions that although the,

‘name “Moreland”, used to designate the municipality, road, and train station, has associational and financial links to eighteenth- and nineteenth- century Caribbean slave plantations’, ‘no definitive historical documents exist explaining why in 1839 Farquhar McCrae selected “Moreland” for his Melbourne property…’ and ‘no historical record identifies Farquhar’s motivations or intentions for naming his colonial Melbourne property “Moreland”.

Thus, Dr Lesh was unable to find any firm documentary evidence that Dr Farquahr McCrae named his Melbourne property ‘Moreland’ after a Jamaican slave plantation.

Therefore, given this lack of firm evidence, and considering the very high cost that Moreland City ratepayers will have to bear to effect this name change, we propose that Moreland City Council should not proceed with the changing of the municipality’s name.

Instead, we propose a ‘re-imagining’ of the derivation of the word “Moreland”.

Given that the use of the name “Moreland” belongs to all residents and ratepayers, we can make the word mean whatever we want it to mean.

It seems to us that a way for the community to avoid division, and the multi-million dollar expense of removing the name ‘Moreland’ from the municipality, is to re-imagine that the word ‘Moreland’ was originally derived from the words ‘moor land’.

When the Scottish immigrant, Dr Farquhar McCrae settled in the Moonee Ponds area in 1839, he named his property ‘Moreland’. It is quite feasible that he was referencing the ‘moors’ and the rocky ‘land’ that characterised the landscape of his place of birth in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The original landscape of Moonee Ponds, Pascoe Vale, Glenroy and Brunswick was very similar to that of around Edinburgh - the grassy plains with volcanic rocky outcrops and occasional swampy creeks with underlying sand and clay beds, the landscape of Dr Farquhar McCrae’s birthplace.

As a society we own the words of our language and we can decide to change the meanings of some of those words over the years if we so decide. This ‘semantic change’ is a well known phenomenon and can lead to words acquiring additional or changed meanings (eg. ‘gay’ [lighthearted/joyous & homosexual], or ‘mouse’ [an animal & a computer accessory].

Most interestingly, some words undergo reappropriation, which is a cultural process by which a word that was previously used in a disparaging way is reclaimed in a positive way as a means of sociopolitical empowerment [eg. ‘queer’, or ‘Bogan’].

Our point here is that, as english-speakers, the rate-payers of Moreland own the use of the word ‘Moreland’ in their municipality - they can reappropriate ‘Moreland’ to mean whatever they want it to mean.

What we are proposing is that the we empower our community by rejecting the claims that our municipality is named after a Jamaican Slave plantation, but rather that ‘Moreland’ is a word derived from the beauty of our local landscape - the Country of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people.

One of the first Scottish settlers, Dr Farquhar McCrae was so moved by the similarity of the area to the ‘moors’ and ‘land’-scape of his place of birth in Edinburgh Scotland that he named his property ‘Moreland’.

Discussion and Supporting Evidence

As we will explain below, there is no real, definitive evidence that Dr Farquhar McCrae himself ever stated that he named his property on the banks of the Moonee Ponds after a Jamaican slave plantation. Even the officially commissioned 2022 report by the Moreland City Council (Ref. 1 and here) into the origins of the name Moreland states that,

‘No definitive historical documents exist explaining why in 1839 Farquhar McCrae selected “Moreland” for his Melbourne property…’ (p6);

‘No historical record identifies Farquhar’s motivations or intentions for naming his colonial Melbourne property “Moreland” (p17), and

‘Calling his property “Moreland” …did not necessarily symbolise an affirmation of slavery by Farquhar.’ (p17)

We will provide evidence for our proposal in the following sections. We will also provide evidence as to why it is very unfair and indeed hypocritical to ‘associate’ Dr Farquhar McCrae himself and his property (and, by association, the ratepayers of Moreland) with a slave plantation that existed half-way around the world in Jamaica, 50 to 100 years before Dr Farquhar McCrae even arrived in Melbourne.

To accuse the community of Moreland today for perpetuating racism by the sole act of living in a place called ‘Moreland” is very unfair and hurtful to many members of our community.

To progress with the name change will, in our opinion, only create division and hurt within our peaceful community. Already community groups are appearing who feel that the name-change decison has been rushed without adequate consultation (see here and here).

A much better approach, in our opinion, is to erase any alleged stains of slavery associated with the name “Moreland” by undertaking a concerted community consultation process to campaign for a ‘re-imagining’ of the derivation of the word “Moreland”.

Our proposal is that we imagine that Dr Farquhar McCrae derived the named his property from the ‘moors’ and ‘land’ of his birthplace, Edinburgh in Scotland.

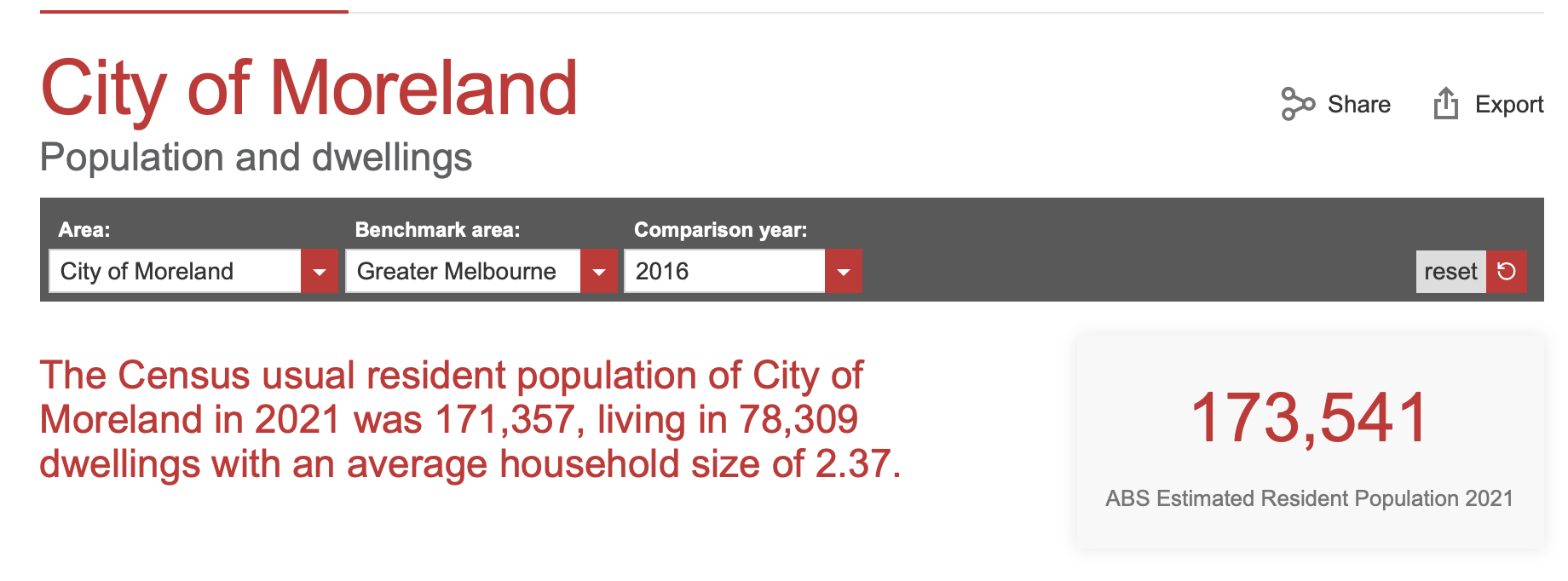

This would be a mature and inclusive community response that should satisfy all parties - Moreland would no longer be associated with the stain of slavery; the Council saves a large sum of ratepayers funds which can then be spent on more worthy community activities; and our colonial heritage and British descendants are respected. In the 2021 Census, 40% of Moreland’s residents identified as being of English, Irish or Scottish descent (See Note 2 below).

Background to the Call to Remove the name ‘Moreland’

The justification by the majority of the councillors within Moreland City Council to change our municipality name from Moreland is based on what these councillors believe are the alleged links between the name ‘Moreland’ and slavery, and the perceived dispossession of the municipality’s land from the traditional Aboriginal inhabitants, by Dr Farquhar McCrae, when he established his Moreland property.

Council believe that,

‘the name “Moreland”, used to designate the municipality, road, and train station, has associational and financial links to eighteenth- and nineteenth- century Caribbean slave plantations’. (Ref 1, p2)

As Moreland Mayor, Cr Mark Riley explains,

“We are shocked and deeply saddened to learn that 27 years ago, Moreland was named after a slave estate. The history behind the naming of this area is painful, uncomfortable and very wrong. It needs to be addressed.” (Source)

Additionally, Council stated that,

‘Information was presented to Council last week by Elders from the Traditional Owner community and other community representatives, showing that Moreland was named after land, between Moonee Ponds Creek to Sydney Road, that Farquhar McCrae acquired in 1839…The land in what is now called the Moreland local government area was sold to Farquhar McCrae without the permission of the traditional owners, who were suddenly dispossessed from their land’. (Ref 5 and here)

Although Council has approved the changing of the municipality’s name from Moreland to Merri-bek, there are dissenting voices amongst some ratepayer groups, who disagree with a number of aspects of this decision by Council namely,

the speed at which the decision has been taken, without they claim sufficient consultation with all the stakeholders in the municipality;

the undemocratic nature of the decision - Council did not allow all rate-payers to have a Yes/No vote on the name change. Ratepayers were only allowed a voluntary vote on the three new name options;

the potentially high cost of the name change to all the municipality’s signage, council stationary and other documentation, as well as the resources required to implement the change over several years. This high cost is particularly concerning given the high interest rate and increasingly inflationary economic times expected over the coming years that will put many households in Moreland, and subsequently our Council, under severe budgetary constraints (see here, here and here).

A Proposal for the Re-imagining the word ‘Moreland’

Our proposal to overcome the perceived negative links between the name Moreland and alleged slavery, and to avoid the high cost of the name change is to ‘re-imagine’ the definition of the word Moreland.

We also believe that it is divisive to the community to erase older colonial names and replace them with Aboriginal names. A much better approach, in our opinion, is to heavily preference, as much as practical, the choice of Aboriginal words for the naming of all new parks, streets, buildings and installations.

The community will be much more accepting of the ‘indigenisation’ of our society if they see it as being creative and adding to our shared community, rather than being destructive and negative by erasing the memory our non-Indigenous community and their history. A mature, successful community knows that it is much better to be creative and build things, rather than be destructive and pull-down things.

A perfect example for Council to show creative leadership is to not spend vast sums of ratepayers money changing the signage from Moreland to Merri-bek, but rather to invest these funds in showcasing the first Aboriginal inhabitants and their heritage in the proposed Moonee Ponds Reclamation Project.

This will be a much more positive way to assist in any ‘healing process’ that some members of our municipality’s Aboriginal residents are calling for.

Evidence Presented by Council for the Name Change

To support the name change, Council commissioned Dr James Lesh of Deakin University in 2021-22 to prepare a, ‘Report on the place name: Moreland’.

Dr Lesh undertook detailed historical research into Dr Farquhar McCrae and the name of his large property ‘Moreland’, which was established from 1839 on the land between Moonee Ponds Creek and Sydney Road, on either side of today’s Moreland Road.

Although Dr Lesh’s report was very detailed, and a credit to his academic skill given the very short time-frame that Council allocated to its completion, Dr Lesh makes a number of statements in the body of his report that seem to contradict the Executive Summary of the report that Council relied upon in coming to its decision to change the municipality’s name.

Dr Lesh’s report actually stated that,

‘No definitive historical documents exist explaining why in 1839 Farquhar McCrae selected “Moreland” for his Melbourne property…’ (Ref 1, p6, here).

‘No historical record identifies Farquhar’s motivations or intentions for naming his colonial Melbourne property “Moreland”. (Ref 1, p17).

‘Calling his property “Moreland” – more than a decade after slavery was abolished, by which time public opinion across the British Empire had firmly turned against slavery – did not necessarily symbolise an affirmation of slavery by Farquhar’ (Ref 1 p17).

‘As noted, Farquhar received only minimal financial benefit during his upbringing from his own family inheritance – tied to Moreland in Jamaica – and brought practically none of it to Australia with him. In contrast, Farquhar had the £6,000 from his uncle John Morison – his wife Agnes’ father – estate. Agnes’ paternal grandparents, the parents of John, were the notable individuals Sir Andrew Morison, Writer to the Signet, and Mary Herdman. A primary source of the Morison family wealth came from the Windsor Castle Estate in St David, Jamaica. (Ref 1, p17-18).

Dr Lesh could find no actual evidence - any letters, quotes or references by Dr Farquhar McCrae himself - that confirmed that McCrae in fact named his property in Melbourne after a slave property, which was located halfway around the world in Jamaica, that his grandfather Alexander McCrae is alleged to have owned before Farquhar McCrae was even born (see family tree birth/death dates in Ref 1, p21 - here).

One of the pillars of our progressive society in Australia is that with regard to human rights, the law and commerce, ‘the sins of the father are not the sins of the son.’ Without any real documentary evidence, it is very unfair to smear the reputation of Dr Farquhar McCrae and associate him with the ‘stain’ of slavery just because his grandfather may have been a slave-owner.

There has never been any Jamaican-style, legal chattel slavery in Australia and Dr Farquhar McCrae’s Moreland property was never a ‘slave’ enterprise - all its workers were ‘free’ men and women and employed under the norms and wages applicable to those times in colonial Australia.

It is therefore our conjecture in this article to imagine that Dr Farquhar McCrae himself was not thinking of any links that his family may have had to slave plantations in Jamaica when he named the beautiful country that stretched from the banks of the Moonee Ponds to Sydney Road.

There is no real Evidence that Dr Farquhar McCrae named Moreland after a Jamaican Slave Plantation

The conclusions we have quoted above, from Dr Lesh’s very detailed historical report, provide the residents of Moreland, we believe, with an opportunity to distance the municipality, from any alleged ‘stain of slavery’ that might be associated with any Moreland slave estate in Jamaica.

Despite much detailed historical research, Dr Lesh has been unable to provide the ratepayers of Moreland municipality with a document that proves that Dr Farquhar McCrae named his Moreland property after a Jamaican slave plantation. Without this real evidence it seems to many of us that it would be a drastic and very expensive exercise to replace all the ‘Moreland’ signage based on something that might not even be true.

In the world of the internet, massive numbers of historical documents are now easily accessible so it is surprising that no original document has actually been presented by Dr Lesh that proves Moreland was named by Dr Farquhar McCrae after a Jamaican slave plantation.

Instead, Dr Lesh relies on the following narrative to justify his ‘joining of the dots’ to ‘infer’ that Moreland was named by Farquhar McCrae after a slave plantation.

‘The most detailed account of the Moreland Estate in Jamaica comes from the McCrae family history recorded between the 1850s and 1880s in Melbourne by both Andrew Murison McCrae (1799–1874), Alexander’s grandson and Farquhar’s brother, and his wife Georgiana Gordon McCrae (1804–1890), held at the State Library of Victoria (henceforth ‘McCrae Records’). Much of this material appears to be in Georgiana’s handwriting, with occasional annotations from their son George Gordon McCrae.

The McCrae Records comprising family memoirs, oral accounts, and older transcribed records and correspondence…[and]…were recorded for private family purposes, rather than the public record, and appear to be less embellished than later material published by the family. Furthermore, the Records mention first-hand conversations with family members and the sighting of original documents, contributing to their reliability.’ (Ref 1, p6)

In other words, it appears that Dr Lesh is relying principally on oral family history accounts, as well as notes by Farquhar’s sister-in-law, Georgiana, written subject to ‘embellishment’ and some 100 years after the family’s ancestors were associated with the Moreland slave estate in Jamaica.

So, a ratepayer of Moreland needs to ask themselves, ‘would I undertake a multi-million dollar exercise of changing the name Moreland based on the hand-written notes of my sister-in-law who lived on the Mornington Peninsula and says she knows what happened in the family history 100 years ago in Jamaica?” Knowing my own sister-in-law, probably not.

Dr Lesh then goes on to say,

‘Place names are difficult to conclusively identify the origins of. Decision makers rarely record the rationale for their choices. No definitive historical documents exist explaining why in 1839 Farquhar McCrae selected “Moreland” for his Melbourne property or in 1994 “Moreland” was put forward as the leading candidate for the name of the new municipality.

Nevertheless, the role of the historian is to analyse and interpret the past, to make reasonable and replicable inferences, based on the records available to them. There are sufficient historical sources to conclude a link between the adoption of the name “Moreland” in Melbourne in 1839 and the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Jamaican slave plantation called the “Moreland Estate”. Farquhar McCrae was almost certainly aware of his family’s Jamaican colonial heritage. His immediate family recorded this heritage on paper in the midnineteenth century and later promoted this heritage in the twentieth century.’ (Ref 1, p6)

Thus, Dr Lesh appears to be saying here that he, as an historian, has read the McCrae papers, found it ‘difficult to conclusively identify the origins of’ the place name Moreland, but ‘nevertheless’ decided that there are ‘sufficient historical sources to conclude a link between…the name Moreland…and the Jamaican slave plantation…’ He seems to be admitting that he is using conjecture to ‘join-the-dots’ to come to perhaps a pre-determined conclusion.

Just How Reliable are the McCrae Family Papers?

Dr Lesh appears to have only published one transcript of a letter he found in the McCrae papers. This letter was written by Andrew McCrae, Alexander McCrae’s grandson. Andrew, who wrote this letter sometime between 50 and 100 years after his grandfather was alleged to have made his wealth in Jamaica, says the ‘informant’ he relied upon for the particulars was his “Uncle” John Christie, who was ‘on the most cousinly terms’ with Andrew’s father William - that is, the information was not even directly from his grandfather but rather is second-hand in nature only.

Dr Lesh, in spite of his very detailed report, has not be able to provide any actual, original document from the McCrae papers that categorically proves the link between Dr Farquhar McCrae’s use of the name Moreland and the Jamaican slave plantation.

To our knowledge, no peer-review of Dr Lesh’s report by suitably qualifed independent historian(s) has been undertaken. No indication has been provided as to whether any member(s) of the report’s Working Group had dissenting views to the report’s conclusions. As far as we know, the Working Group were possibly all in favour of the name change of Moreland from the outset.

To many of us, this appears to be a huge responsiblity to put on Dr Lesh and his single report, authored solely by himself.

In effect, Council is relying on the historical inferences drawn by one academic alone, employed on a short-term contract, to provide the justification for a multi-million dollar change to the municipality’s signage that will take years to complete. And all without serious community consultation.

Re-Imaging the name Moreland

We can’t change the past but we can decide how we engage with it today.

The proposal put forth in this article asks us to accept the historical fact that Dr Farquhar McCrae did establish a property which he called Moreland on the banks of Moonee Ponds Creek in 1839, but that there is no actual evidence or documentary proof that McCrae named this property after a Jamaican slave plantation.

Similarly no evidence has been found where Dr Farquhar McCrae himself records that he named his Moreland after a Jamaican slave plantation. All we apparently have are McCrae family stories, diaries, notes and historical heresay that appeared up to 100 years after grandfather Alexander McCrae was believed to have been associated with a slave plantation called Moreland in Jamaica.

We also know that Dr Farquhar McCrae’s father William had been disinherited, so no inheritance flowed from Farquhar’s grandfather to his son William or grandson Farquhar. Farquhar McCrae did not bring any funds to Australia that had been sourced from any Moreland slave plantation in Jamaica.

Thus, it seems perfectly reasonable for us of today to simply re-interpret or re-imagine the derivation of the word Moreland to suit the progressive narrative we wish for our municipality today - that is, we propose that ‘Moreland’ is a derivation of the ‘moor land’ of Dr Farquhar McCrae’s beloved place of birth, in the country-side around Edinburgh, Scotland.

This is an idea that Dr Lesh touched on his Moreland Name Report to Council. Dr Lesh also concedes that it might have been possible that Dr Farquhar McCrae named his Moreland Estate after a place in Scotland or in reference to the landscape in Scotland when he writes,

‘The [McCrae] family [in 1850-1880] also has no recorded links to any such place – Moreland, Moor Land, the Moors, or so forth – in Britain’. (Ref 1, p6)

What we are saying in our proposal is that, even if Dr Lesh could find no direct record in the McCrae papers that Dr Farquhar McCrae based his property name on the ‘moorlands’ and landscape of Scotland, Dr Lesh at least admits that Farquhar could have been so motivated - it was reasonably possible that Farquhar did in fact do this. That is why Dr Lesh specifically looked for this possibility in the McCrae family records.

In the next section we will discuss the landscape similarities between Dr Farquhar McCraes place of birth in Edinburgh, Scotland and his new home Moreland, on the banks of the Moonee Ponds.

Landscape Similarities between the Moor Lands of Scotland and Moreland in Melbourne

It is our proposition that the residents of Moreland could easily believe and justify that Dr Farquhar McCrae named his property after the ‘moors’ and ‘land’-scape of his birthplace, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Consider Figure 1 below, which is a photograph of a typical ‘moorland’ in Scotland. Then compare it to a 1930 view of the landscape along the valley of the Moonee Ponds Creek in Figure 2.

In many ways, these two views from opposite sides of the earth look similar - similar enough that perhaps a Scotsman might fondly notice the similarity.

Figure 2 - The view in 1930 Along the Valley of the Moonee Ponds Creek at Glenroy and wetlands, not far from Farquhar McCrae’s “Moreland” . Looks not unlike the adjacent ‘moorland’ in Scotland. (Source Broadmeadows Historical Society No. 172e, Org ID: G5_1)

We can’t be exactly sure what the landscape was like when McCrae first arrived in 1839, but most likely it consisted of grassy plains with few, if any, scattered trees, intersected by the creeks and swamps that constituted the Moonee Ponds.

These plains were possibly kept open and grassy by the fire-stick practices of the Aboriginal inhabitants and thus were considered prime gazing and farming lands by Farquahar McCrae.

From the Moreland City Council’s own website we are told the following about the municipality’s geology and landscape.

‘Shaping Moreland’s Environment - This thematic history begins with the ancient geological landscape formed by volcanic activity and moves on to those who first lived in this part of the traditional Woiwurrung Country; the Wurundjeri-willam. Of particular significance are the two major waterways, Moonee Ponds Creek and Merri Creek which played an important role in Wurundjeri life. These creeks served as a link to the cultural past of present-day Wurundjeri people as they were traditionally important living areas, meeting and gathering places….’

‘Most of the municipality of Moreland ranges between the natural delineation created by Moonee Ponds and Merri Creeks, and intersects with the great lava plains formed by ancient volcanoes to the west and north that began in two major phases erupting millions of years ago. The flows created great beds of basalt, and as time progressed the rock weathered and broke down to create the plains of shallow soils, which typify much of Moreland and resulted in two distinctive resources of stone and clay being formed that would become significant to its post-colonial development. This flat, windswept open country supported sparsely wooded forest and grasslands that became distinctive of this area…’ (Ref 3, p24).

As Farquhar McCrae knew from his youth, Edinburgh possessed a similar landscape,

‘Within the city of Edinburgh, Scotland are the hilly remnants of a long-extinct volcano. On top of one of these hills is Arthur’s Seat, a rocky crag that towers 823 feet (251 m) above the city below. The hills and moors, cliIs and lochs, and marshes and bogs surrounding Arthurs Seat all form part of Holyrood Park’ (Ref 4, p1).

Indeed, another McCrae family farm, located across Port Phillip Bay on the Mornington Peninsula, was called Arthur’s Seat after the nearby mountain by the same name, which was named after the Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh (Ref 2 ).

Figures 3 and 5 below show typical geological formations on the rocky outcrop of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh Scotland, rock formations that Farquhar McCrae very likely knew of as a young man growing up in Edinburgh.

It is our proposal that he very well could have been reminded of this Scottish landscape, by the rocky outcrops along the Moonee Ponds Creek, and by the grassland landscape of his farm, when he arrived in 1839, as shown in Figures 4 and 6.

Figure 3 - This is 'Hutton's Section' of Salisbury Crags, Holyrood Park, Edinburgh, Scotland. Source

Figure 5 - Old photograph of people having a picnic on Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh, Scotland. Arthur's Seat is the main peak of the group of hills in Scotland which form most of Holyrood Park… situated in the centre of the city of Edinburgh, about 1 mile to the east of Edinburgh Castle. Source

As part of our project, we did various GoogleMap searches in the Edinburgh region for words such as ‘Moreland’, ‘Moor Land’ and ‘Morland’ with other word combinations.

A GoogleMap search of the words, ‘Moreland House Cleish Scotland’, located a property by that name north-east of Edinburgh as shown in Figure 7 below (top left corner). This shows that the name ‘Moreland’ might not have been unusual for a property in Scotland.

We have located a birth record that indicates that Farquhar McCrae was born in Currie in the country-side outside Edinburgh - bottom of Figure 7 Map (See here for his birth record).

The rocky volcanic outcrop of Arthur’s Seat is indicated in the map as being in central Edinburgh in the Figure 7 Map.

One wonders whether the painting by Farquhar’s sister-in-law, Gerogina McCrae of her property on the Mornington Peninsula with the Australian Arthur’s Seat towering in the background, is not reminiscent of the view Farquhar might have had of the Scottish Arthurs’s seat when viewed from his birthplace at Currie (See Figure 8).

Also interestingly is a nearby town called Aberlady, which is described as being a place of ‘Moorland, farmland and brickworks’. This has strong parallels to the landscape in which Dr Farquhar McCrae establish his Moreland property - an area of moorland, farmland and the massive future brickworks in our Brunswick (Figure 10).

Figure 7 - Landmarks around Edinburgh in Scotland relevant to Dr Farquhar McCrae - his birth place in Scotland at Currie (some say it may have been near Leith); Arthur’s Seat, the name of his brother’s farm on the Mornington Peninsula; ‘Moreland House’ indicating that it was a common enough property name in Scotland, and Aberlady, the ‘moorland’ and clay brickworks town suggesting the brickswork’s town of Brunswick in Melbourne.

Figure 8 - Georgiana McCrae’s watercolour of her Arthur’s Seat homestead on the Mornington Peninsula and the surrounding bush with the mountain Arthur’s Seat in the background. This suggest that the Scottish settlers in Australia commonly referenced their Australian properties after the landscape of Scotland. Source

There is plenty of evidence that the colonial Scottish settlers to Melbourne named areas of their new home after places in Scotland. The following Melbourne suburban names are believed to be named after, or greatly influenced by, names of places in Scotland

Abbotsford (Scottish Borders - the residence of Sir Walter Scott) - Ardeer (North Ayrshire Scotland, where Nobel's Explosives factory was and the site of their Melbourne factory) - Armadale (two places in Highland and one in West Lothian) - Arthur's Seat (mound in Edinburgh) - Avondale Heights (Avondale in the Shetland Islands and Avondale Castle in Lanarkshire) - Blairgowrie (Perthshire, Scotland) - Braeside (Aberdeen City and Inverclyde) - Broadmeadows (Dumfries & Galloway and three places in the Scottish Borders) - Burnside and Burnside Heights - in Angus & Fife, Moray, South Lanarkshire and West Lothian. ‘Burn’ being a Scots and northern English word for a creek or stream.

Cairnlea (South Ayrshire and Stirling) - Calder Park (Calder in Highland and Renfrewshire, both minor rivers) - Campbellfield (Campbell is a well-known Scottish family name) - Chirnside Park (there is a Chirnside in the Scottish Borders) - Clyde and Clyde North (named after the River Clyde, Scotland) - Coldstream (The Scottish village of Coldstream, birthplace of the Coldstream Guards) - Craigieburn (The suburb took its name from an old bluestone inn, named after the village in Dumfries-shire east of Moffat) - Flemington (Angus, Scottish Borders and South Lanarkshire) - Gladstone Park - (Gladstone is a Scottish family name) - Glen Huntly (there is a Huntly in Aberdeenshire, Scotland ) - Glen Waverley and Mount Waverley (Waverley is the main railway station in Edinburgh) - Glenferrie (Connection with Scotland via a property in the area owned by a Scottish settler and solicitor, Peter Ferrie) - Glenroy (valley in Lochaber, Perthshire, Scotland & a place in Inverness-shire) - Gowanbrae (Gowan is a Scots word for a daisy, 'brae' means a hill or hillside.) - Greenvale (Highland, two places in the Orkney Islands and one in the Shetland Islands) - Hume (Scottish Borders - The Hume/Home family was powerful in the Scottish Borders ) - Keilor (Perth & Kinross, spelt Keillour; also Inverkeilor in Angus) - Kilsyth and Kilsyth South (Kilsyth a town in North Lanarkshire, near Glasgow) - Knox and Knoxfield - (Knox Hill in Aberdeenshire, Knox Knowe in the Scottish Borders and Knoxfauld in Perth & Kinross) - Macleod and Macleod West (named after Scotsman Malcolm Alexander MacLeod) - McCrae (this suburb on the Mornington Peninsula was named for Andrew and Georgiana McCrae) - McKinnon (the MacKinnons are a branch of the Clan Alpin) - Niddrie (Edinburgh and Longniddry in East Lothian - comes from 'newydd' meaning "new") - Rosanna (suburb was named for Elizabeth Anne Rose a Scottish immigrant) - Roxburgh Park (Roxburgh in the Scottish Borders) - Spotswood (Scottish Borders, spelt Spottiswoode. The spelling of the name of this suburb was originally 'Spottiswoode', as in Scotland) - Strathmore and Strathmore Heights (Gaelic for 'big valley'- found in Aberdeenshire, Angus, Argyll & Bute, Highland, and Perth & Kinross). - Source

Figure 9 - Description of Aberlady, a town near Dr Farquhar McCrae’s hometown of Edinburg, Scotland. Not the use of the word ‘moorland’.

Figure 11 - A photograph from 1860-70 of a clay potter’s works in Brunswick. Source p27

Figure 10 - Hoffman Brickworks in Brunswick. Since the earliest days of the Victorian colony, Brunswick and the surrounding suburbs that now make-up Moreland City were places of industry. Indeed, brick manufacturing in Brunswick began in the 1840s and continued until 1993!

Brickwork, quarrying, and pottery were the economic backbone of Brunswick well into the 20th Century. They shaped its character - its streets, its parks, and its people (Source )

The point we are making, by identifying these locations in this Figure 7 GoogleMap of the Edinburgh region, is just to illustrate the similarities of the two landscapes in Dr Farquhar McCrae’s life. His new home in our Municipality, where he could have easily found a landscape to remind him of his old home in Scotland - the volcanic landscape of his birthplace in Edinburgh, where it is easy to find a house called ‘Moreland’, where the word ‘moorland’ is used to describe the countryside and where brick-making was a basic industry.

The similarity with the land on which McCrae settled to the north of Melbourne is so uncanny that it is completely believable that Dr Farquhar McCrae derived the name Moreland from the common word ‘moorland’ of his homeland.

Why it is Very Unfair to Besmirch the Name and Legacy of Dr Farquhar McCrae

Dr Farquhar McCrae’s Medical Legacy to our Community

Figure 12 - The portrait of Farquhar McCrae by his sister-in-law Georgiana. Source

Dr Farquhar McCrae has been credited with the introduction of the stethoscope to Australia (Ref 8).

He had ‘spent 2 years working in Paris where he studied the practical aspects of medicine, surgery and midwifery’.

In particular, he worked 'with the physician M. Louis ‘and through him acquired a self-imposed discipline of patient investigation particularly in relation to chest diseases and the use of the stethoscope. He daily performed operations on the dead body under the patronage of some of the leading surgeons in Paris’ (Ref. 9, p68).

Figure 13 - Source Reference 8

So next time the doctor uses a stethoscope on your sick child, who has a deep cough and chest infection, spare a thought for Dr Farquhar McCrae’s progressive and pioneering work.

Rather than denigrate the memory of Dr McCrae, we as a community should be thankful and commemorate his great contribution to Australian medicine.

In fact, Council should consider installing a memorial plaque to Dr McCrae, perhaps in one of the municipality’s hospitals, in recognition of his pioneering legacy.

Figure 14 - Modern use of the stethoscope, a medical technique introduced to Australia by Dr Farquhar McCrae.

Council’s Lack of Consultation and Respect for Democracy

It has been reported that some residents of Moreland are upset that residents were not adequately consulted by Council prior to the municipality’s name change.

Some residents have claimed that, ‘the move to change the name was presented as a fait accompli, with surveys only offering options to choose from three pre-determined names’.

Others are concerned that, ‘if you don’t involve the community ... in such a big change, you’ll have a community that’s divided.’ (Source)

This decision to change the municipality’s name without adequate community consultation is likely to be divisive and could possibly cause significant hurt for some members of our community.

In addition, the un-democratic nature of the decision is all the more disappointing given that our ancestors, when faced with a similar situation back in 1920 were mature and professional enough to provide a full, democratic vote to residents on such an important matter as the municipality’s name change.

In the years following the end of the First World War in 1918, there were still some sections of the community in Coburg that harboured an anti-German sentiment. On August 26th, 1920, a motion was put to Coburg residents to change the town’s name from the German-derived “Coburg” to “Moreland” (Ref 1 p19)

Figure 15 - A ballot paper from the 1920 referendum to change the name of Coburg. It was not successful. Source: Coburg Historical Society collection

The motion was defeated and the name “Coburg” was retained.

The point however, is that residents in 1920 were given a democratic choice to exercise their free vote.

Incredibly, our Council one hundred years later has failed to show a similar respect for democracy by allowing its residents to vote on exactly the same issue.

Many members of the community are asking just how hard would it have been for the Council to show some democratic responsiblity and include say, a small additional ballot paper in our next council election with a Yes/No question on whether we approve changing our name from “Moreland” to “Merri-bek”?

So Where to From Here?

In summary, our proposal is for Council to:

- plan for an additional ballot paper to be included in the next council elections with the simple Yes/No question

Do you want to change the name of the municipality from “Moreland” to “Merri-bek” ? - Yes / No

- if “Yes” is successful, Council to proceed as originally planned with the name change;

-if “No” is successful, Council to proceed with the ‘re-imagining’ of the name of “Moreland” This will involve consultation with the community and an education program built on progressive principles detailing Council’s opposition to any percieved links between the name ‘Moreland” and slavery. Instead, ‘Moreland’ will be ‘re-imagined’ as being derived from the traditional Aboriginal landscape of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people and its close resemblance to the landscape of the Scottish ‘moors’ and ‘land’ around Edinburgh, Dr Farquhar McCrae’s birthplace;

-undertake some educational ‘dual plaquing’ if required. We are very supportive of the community being told of alternative and competing narratives of our history. An example might be as is illustrated in the ‘re-imagined’ street sign below (Figure 16). This explains our collective history without having to hide or destroy any part of it;

- provide for a rehabilitation of Dr Farquhar McCrae’s reputation in Moreland by including on the Council website references to him being ‘the father of the stethoscope in Australia’ and, as such, a resident of Moreland that we all can be proud of, and

- ensure as far as practical that Aboriginal words are used for the naming of all new parks, streets, buildings and installations.

Figure 16 - ‘Dual plaquing’ of a ‘re-imagined’ Moreland Historical sign to explain the ‘re-imagining’ of the name Moreland.

Many of us think that the ‘hate campaign’ against Dr Farquhar McCrae has been very unfair and, on balance, we believe he should be remembered for the good he brought to our community and the country. There is no evidence that in his own time that he supported slavery. His property Moreland in Melbourne was never operated by ‘slaves’.

The municipality of Moreland today is a community of people from all parts of the world, many of them maintaining elements of their rich diversity of cultures and languages, which they pass onto their next generation via their family traditions as well as in their specialist schools and churches.

The descendants of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Aboriginal people are also rightly free to pass on their own histories and practice their culture and traditions in our community without fear or restriction.

All many of us are asking is that the descendants of the British, Irish and Scots in the City of Moreland be allowed the same respect (40% of residents of Moreland are from these ethnicities, compared to only 0.6% who identify as Aboriginal - Note 2 below for ABS Census).

It is not fair nor right for some politically active members of our community to try to ‘erase’ the legacy and history of the British and Scots in our community. Many of us feel that this is being attempted without the consultation that we expect in a mature, free, informed and democratic society.

Successful communities are fragile. One only needs to look at the failing states and communities in Sri Lanka, Lebanon, Crimea and Ukraine, Hong Kong, Zimbabwe, Cyprus, Venuzeula and even in downtown San Francisco, Seattle and Portland in the US, to understand that we must never let ethnic or political factions become so powerful that they cause divisiveness and hatred within our municipality.

In our opinion, our proposals will satisfy the majority of the ratepayers of Moreland by being consultative with the community, democratic and inclusive of community, not divisive of community.

Ref 1 - Dr James Lesh, Report on the place name: Moreland, Deakin University, April 2022, here

Ref 2 - Arthur’s Seat Victoria Wikipedia

Ref 3 - Moreland Council Website

Ref 4 - Corlyss Clayton, Exploring Arthurs Seat, (Source)

Ref 5 - Moreland Council website here

Ref 6 - Georgina’s Journal, Hugh McCrae (Ed) Angus & Roberton, 1934 (1966)

Ref 7 - Describing the name of the McCare family property on the Mornington Peninsula, Georgina McCrae writes in her journal on the 17th of April 1844,

‘Because I had objected to our run being called “Wango” (the native appellation of the survey), it has been decided to retain the name of Arthur’s Seat, originally given to the mountain when first seen from the deck of Flinder’s ship [sic] by Lieutenant Murray, forty years ago. The Spring of water is already anticipatorily chiristed “St Anton’s Well'“. (Ref 6, p137). (Note 1)

Thus the wife of Farquhar’s brother Alexander, Georgina McCrae was quite comfortable in naming the McCrae’s land holdings on the Mornington Peninsula after a landmark from her hometown of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Ref 8 - Gandevia, B., The Evolution of the Stethoscope…, The Medical Journal of Australia, 14 May, 1960, p782ff,

Ref 9 - Pearce, R. Farquahr McCrae MD - Portrait of a Surgeon, Aust. N . Z . J . Surg. 1986, 56, 67-72 here

Ref 10 - Sowell, T., Race and Culture, Basic Books, 1994

Ref 11 - Windschuttle, K., Why Australia Had No Slavery, Part III: The Founders, Quadrant Magazine, 20th June 2020

Notes and Further Reading

Note 1 - The City of Moreland decided at a Special Council Meeting at Glenroy Community Hub on Sunday 3 July 2022 to change the name of Moreland City

Council to Merri-bek City Council.

Council intends to make provision for an expenditure of ‘$250,000 per year for 2 financial years ($500,000 in total) to update Council’s digital platforms, signs at significant Council buildings and facilities, and municipal entry signs’. Further ‘updating other Council assets such as street and park signs and smaller facilities signage will be staged over a 10-year timeframe within existing budget allocations and asset renewal programs’. - here

Critics of the proposal suggest that the true cost of the name change could well be in the ‘millions’ of dollars - ‘independent [Moreland City] councillor Oscar Yildiz said the real price could total millions for locals and it was “not the time” for such a change. “In the long-term I think it’ll end up costing millions,” he told the Herald Sun newspaper. “The $500,000 is over two years but a lot of that money will go towards consultation.”’

-The Australian, 14 December, 2021

Note 2 - Moreland’s ABS Census Results 2021

According to the ABS Census figures of 2021, 40% of Moreland’s residents were of English, Irish or Scottish descent. Only 0.6% were of Aboriginal descent.

Further Reading

Are We All Linked to Slavers and Slaves in Some Way?

In the Executive Summary section of his report to Council on the origins of the place name ‘Moreland’, Dr Lesh of Deakin University dug deep into the archives to find any possible link whatsoever between the Melbourne’s McCrae family and the practice of slavery, not in Australia but in Jamaica.

As we discussed in the section above, although Dr Lesh states in his Executive Summary that,

‘The name “Moreland”, used to designate the municipality, road, and train station, has associational and financial links to eighteenth- and nineteenth- century Caribbean slave plantations. The name was first adopted locally on Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Country by Scottish settler, doctor, speculator, and firebrand Farquhar McCrae (1806–1850).’

In our opinion this might be very unfair to the McCrae family. For example, how do we know that members of today’s Council, who are passing judgement on the McCrae family, don’t also have some associational links to slavery themselves? It would be most unfair for commentators today to call out the alleged links to slavery of the McCrae family without first assuring Moreland’s rate-payers that their own families are free of the blemish of slavery.

Three of commentators who we understand are calling out for the name change of ‘Moreland’ themselves also have names of British heritage - Moreland Mayor Cr Mark Riley, Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung elder Uncle Andrew Gardiner, and Australian Senator Lidia Thorpe.

Moreland Mayor Mark Riley (Source)

Muslim Indigenous Elder Andrew Gardiner and his wife Sadika Kassab (Source)

As far as we are aware, none of these three commentators have provided any evidence to show that they and their families have no historical associational or financial links to slavery.

Now, we are not alleging they in fact do have any links to slavery but, to avoid any hypocrisy in their arguments, it would be comforting for the ratepayers of Moreland to be assured that they and their ancestors are free of such links.

If we use the exact same slavery data base that Dr Lesh used in his research report to Council, namely the University College London – Legacies of British Slavery online database, and we search for the names of Riley, Gardiner and Thorpe, we find the following slavery links to these family names:

Figure 17 - Caribbean Slavery links to the family name ‘Riley’ - the same family name as the Moreland Mayor Cr Mark Riley. (Source)

Figure 19 - Caribbean Slavery links to the family name ‘Thorpe’ - the same family name as Victorian Senator Lidia Thorpe (Source).

Figure 18 - Caribbean Slavery links to the family name ‘Gardiner’ - the same family name as Moreland’s Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung elder Uncle Andrew Gardiner. (Source)

Similarly, if we are going to erase the name Moreland because there was a slave plantation in Jamaica with the same name, what about our suburbs of Brunswick and Glenroy?

How do we know that these suburbs don’t also have an associational link to slavery?

Has Council made an assessment are as to whether these suburbs owe their names to the Caribbean slave plantations of the same name? (see Figures 20 and 21).

Figure 20 - There were slave plantations in Jamaica named ‘Brunswick’. Should Council investigate if the name of our suburb has historical links to any of these slave estates? (Source).

Figure 21 - There was a slave plantation in Trinidad named ‘Glenroy’. Should Council investigate if the name of our suburb has historical links to this slave estate? (Source).

Now, we are not claiming that the suburbs of Brunswick and Glenroy, or Mayor Mark Riley, Uncle Andrew Gardiner nor Senator Lidia Thorpe have links to the slave plantations of the Caribbean - we haven’t done the detailed historical or genealogical research that would be required to determine this.

But likewise, how do we know they don’t have links to slavery?

Thirty or so years ago no-one had apparently done the research to make any link between the name Moreland and a Jamaican slave plantation, but now Council is embarking on a multi-million dollar name change based, in our opinion, on only tenuous and recent evidence.

Shouldn’t Council slow down and consider the long-term consequences and costs of opening this name-changing ‘can-of-worms' ?

Truth-Telling Works Both Ways - ‘Slavery’ in Australia

There appears to be a ‘hate campaign’ against Dr Farquahr McCrae by ‘anti-slavery’ activists in Moreland. However, McCrae himself never owned or sold any slaves.

In comparison, the following are real-life, more recent examples of Australian Aboriginal men ‘enslaving’ their own Aboriginal women and young girls by ‘selling’ them. Does this mean that we should stop naming places in Australia after Aboriginal men?

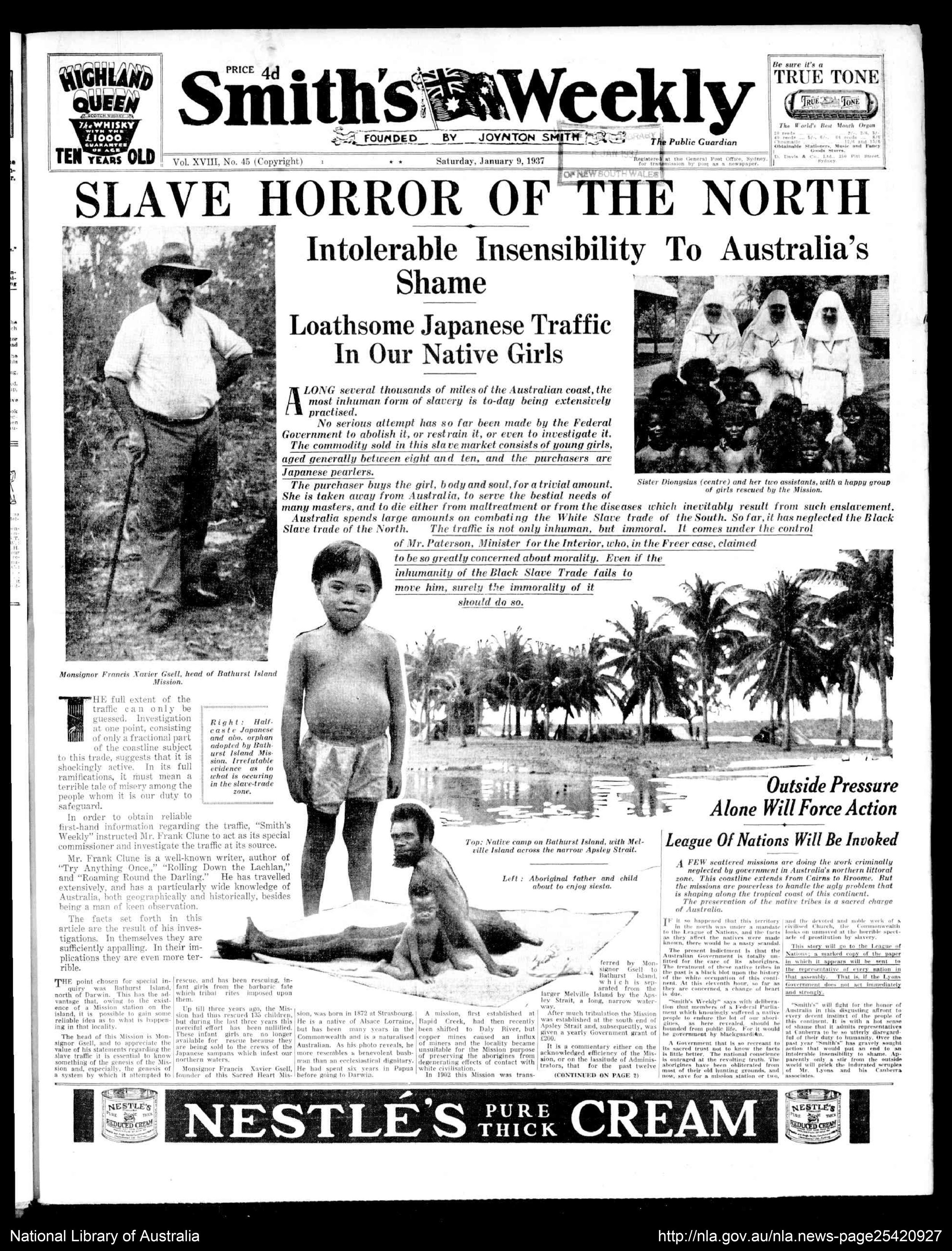

On the 9th of January 1937 Australians woke up to read a shocking major news story that organised ‘slavery’ was occurring in Australia.

It was reported that Aboriginal girls as young as 10 were being sold or traded for cash and goods with Japanese pearlers, who visited northern Australia in their fishing boats.

Figure 22 - Newspaper Reports of Aboriginal Slave trading. Read an abridged text here. Source: SLAVE HORROR OF THE NORTH Smith's Weekly, Sat 9 Jan 1937, p1

Figure 23 - News of Aboriginal slavery - Southern Cross Newspaper (Adelaide, SA) Fri 9 Oct 1936, p7

This story on Aboriginal slavery had been brewing for a while and had started to leak out in the previous year, 1936.

Small news items had begun to alert Australians as what was happening:

‘…Monsignor Gsell said that the blacks took their women on to the pearling luggers and bartered them for food, tobacco, and other goods. The practice had increased to an alarming extent in the last two years. The mission had a serious task in caring for the 2,000 aborigines on Melville Island and Bathurst Island in the face of the degenerating influences introduced by the visits of scores' of Japanese luggers.

When pearling operations were suspended during the very high tides as many as 70 Japanese luggers, in addition to Australian-owned boats, anchored off the coast.' Girls as young as 10 years had been traded…

Monsignor Gsell said that frequent visits by the Government patrol boat Would assist in checking the evil. The elimination of the practice could be accomplished gradually by the training of aboriginal children. The mission was undertaking this work. Monsignor Gsell described a feud which has resulted in several fights among blacks on Bathurst and Melville Islands. The feud began about two years ago, following a dispute between two natives over a 12-year-old lubra, and it appeared that the whole aboriginal population of 2,000 was now involved…

Professor A. P. Elkin, of the Department of Anthropology at Sydney University, said that "apparently the aborigines of Bathurst Island are addicted to the trading of their women and girls to the Japanese for the sake of a stick of tobacco or a bag of flour. It must be stopped for the good name of Australia."

Commenting on the charges made by Monsignor Gsell, principal of the Bathurst Island Catholic Mission, that aboriginal women and even girls of 10 were bartered to the Japanese, who came to the island in luggers, Professor Elkin said that the Monsignor was such a reliable authority that there could be no doubt that the practice was still going on. While biologically there is nothing against such a blood mixture, the trade in women could not be permitted. "Some time ago this trading of aboriginal women to the Japanese was very common around Broome, but increased vigilance by the West Australian Government stamped it out. There would not be so much of this looseness among the aborigines of those parts if -they had any idea of the evil consequences of their actions in trading their women for goods," declared the professor.

- Source: Southern Cross (Adelaide, SA), Friday 9 October 1936, p 7.

Figure 24 - News that Government efforts to curtail the slave trade in Aboriginal girls was being successful. Source Daily Guardian (Perth, WA) Wednesday 25 August 1937, p1

The Commonwealth government responded swiftly and the practice was finally stopped, ostensibly by removing the Japanese ‘customers’ .

A number of independent historians have written about Aboriginal societies treating their young girls as ‘tradable goods’ and ‘slave’ labour.

One of Australia’s most respected historians, Professor Henry Reynolds provides many examples of Aboriginal societies ‘enslaving’ their own young girls. In his 1995 book, The Other Side of the Frontier, Professor Reynolds writes of how Aboriginal men traded in the sexual favours of their women.

Professor Henry Reynolds, an academic specializing in Aboriginal and colonial history

‘Many Aboriginal groups discovered that prostitution provided a more certain return than…hunting and gathering. In some places a large and lucrative trade developed and especially around the northern coasts where prostitution became one of the essential service industries supporting the pearling fleets…

…The trading with young girls is very profitable to the natives…as for one nights debauchery from ten shillings to two pounds ten is paid in rations and clothing…

Money and food earned by the women was shared in the fringe camps allowing most of the men to avoid the need to labour for the Europeans [and] to make a living in ease and idleness.’ (ibid. p146.)

‘..[I]ndigenous entrepreneurs…Waimara and James were the ‘bosses’ who organised labour for the luggers and women for the crews.’ (ibid. p146-147.)

A leading academic on Aboriginal, Australian and Feminist history, Professor Lyndall Ryan, also describes similar ‘enslavement’ practices by Tasmanian Aboriginal societies in her book, The Aboriginal Tasmanians.

Professor Lyndall Ryan

Professor Ryan writes of the sealers of the north coast of Tasmania, who came from Sydney, the United States and Britain from 1804 onwards:

…“[their] visits coincided with the Aborigines’ summer pilgrimage to the coast for mutton birds, seals, and birds and their eggs. Most Aboriginal groups were at first cautious of these visitors, but it was not long before they were willing to exchange seal and kangaroo skins for tobacco, flour, and tea.

This contact intensified when the Aborigines offered women in an attempt to incorporate the visitors into their own society. When the sealers reciprocated by offering dogs, the means were provided for mutually advantageous interaction…

By 1810 the North East [Aboriginal] people had begun to gather each November at strategic points along the north-east coast…in anticipation of the dealers’ arrival. After their appearance, usually in a whaleboat containing four to six men, a dance would be held, a conference would take place, and an arrangement would be made for a number of women to accompany the sealers for the season. Some women came from the host band, while others were abducted from other bands and sold to the dealers for dogs, muttonbirds, and flour...

Once the economic value of Aboriginal women in catching seals was exploited by the sealers, the economy and society of the North East people changed. They now remained on the coast for the whole summer instead of moving inland to hunt kangaroos. In winter they [the Aboriginal people] went in search of other bands and tribes along the coast to abduct their women.

The power and influence of individual leaders like Mannalargenna…also increased. He led many raids for women on other bands, negotiated with sealers, and quickly saw the value of European dogs to the Aboriginal economy and gift exchange system.”

- Lyndall Ryan, The Aboriginal Tasmanians (UQP, 1982 reprint, p69 – 71).

Aboriginal ‘slavery’ in the form of Aboriginal societies selling and trading their young girls for goods could also have an ‘international-trade’ aspect.

There is an ample oral history record by Aboriginal people themselves that their ancestors in the not too distant past ‘enslaved’ their own girls by shipping them off to Indonesia (Makassar) in a type of international slave trade.

In the following film clip Aboriginal Elder, Dorothy Djanghara, provides oral history on how Aboriginal girls were traded as ‘slaves’ with the Indonesians (Makassian fishermen) in NW Australia prior to British settlement. Watch from about 03:12.

Was there a form of ‘slavery’ amongst the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people themselves?

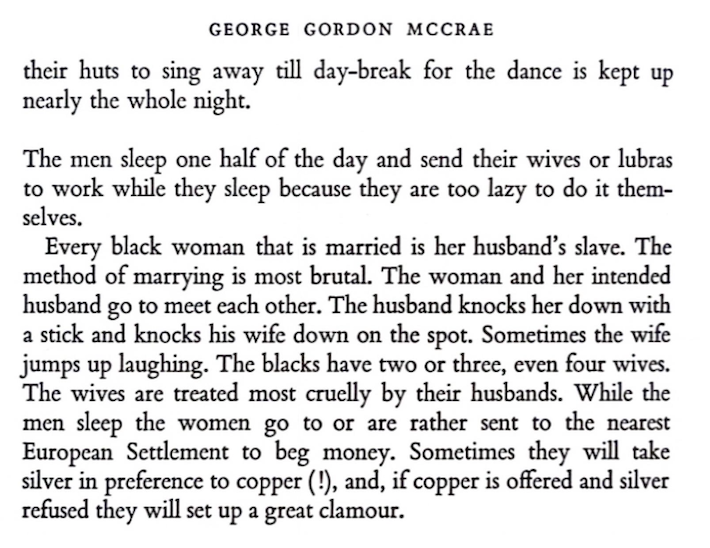

Dr Lesh relies heavily on what he terms the McCrae family papers in coming to his conclusion that the McCrae’s had associational links to Jamaican slavery. Dr Lesh writes that the McCrae family papers consist of,

the McCrae family history recorded between the 1850s and 1880s in Melbourne by both Andrew Murison McCrae (1799–1874), Alexander’s grandson and Farquhar’s brother, and his wife Georgiana Gordon McCrae (1804–1890), held at the State Library of Victoria (henceforth ‘McCrae Records’)’

Georgiana’s Journal, along with some diary fragments of her son George Gordon McCrae are a selection of the McCrae family papers that have been published by the family, in book-form in 1934. Below are a few excerpts from the book relating to the years around the mid 1840s which relate to Georgiana’s and her son George’s recollections of how the local Aboriginal men treated their wives as near ‘slaves.’

To some members of the Moreland community, it seems very unfair to criticize Dr Farquhar McCrae’s choice of Moreland for his property’s name because his grandfather may have allegedly had some association with a Jamaican slave plantation, when in fact documented cases exist of forms of ‘slavery’ that were actually practiced by Aboriginal people themselves.

We notice that Indigenous Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Elder, Uncle Andrew Gardiner is of the Muslim faith. It seems very unfair for Uncle Andrew to be a critic of Dr Farquhar McCrae for the alleged associational links to slavery associated with the name of his Moreland when Islam itself is hardly blame-free when it comes to the history of slavery.

The history of slavery in the Muslim world is as horrific, if not more so than the British slave trade in the Caribbean. It is estimated that slavery in the Muslim world engulfed the lives of some 11 - 15 million slaves (Source).

It was the British who first began the process of the abolition of slavery, starting in the 1780’s. Indeed Dr Farquhar McCrae’s own father William McCrae was said to be an Abolishionist.

In contrast it was not until the,

‘1950s–1960s, that a majority of Muslims had accepted the abolition of slavery as religiously legitimate. By the end of the 20th century, all Muslim countries had made slavery illegal. In 1926, the Muslim World Conference meeting in Mecca condemned slavery [and now] most Muslim scholars consider slavery to be inconsistent with Quranic principles of justice…However, certain contemporary clerics still consider slavery to be lawful, such Saleh Al-Fawzan of Saudi Arabia’. (Source).

In our opinion it is very unfair for Uncle Andrew Gardiner, as a follower of the Islamic faith, to be ‘part of a delegation that met Moreland’s Greens mayor Mark Riley and chief executive Cathy Henderson and informed them of the name [Moreland’s] links to slave labour.’ (Source)

It would appear to us that the Islamic world should hang its head in shame given the slowness with which slavery was eliminated in the Islamic world compared to Britain’s dominions. Saudi Arabia, the home of the holy city of Islam, Mecca, did not ban slavery until 1962, within living memory of many residents of Moreland municipality.

Although the racism of slavery is historically deeply embedded within Islamic culture - the word 'abd [abeed] is Arabic for both "slave" and “black” or “anyone who had darker skin than oneself” - we would not expect the Moreland City Council to make pronouncements about the use of the word “abeed” amongst Arabic speaking residents in our municipality.

Nor would we expect Council to restrict access to the Koran and ban the teaching of it even though it contains passages such as quotes from the Prophet Muhammad, "You should listen to and obey your ruler even if he was an Ethiopian [ie black] slave whose head looks like a raisin" (Sahih Bukhari Volume 9, Book 89, Number 256) (Source).

This compares to modern Australia, which is we understand is one of the very societies or countries in human history not to have had a history of legal chattel slavery.

Indeed, Australia still takes the crime of slavery very seriously and will prosecute anyone, no matter what their race or ethnic backgound, who tries to engage in slavery here (See Figure 25).

Figure 25 - Real life ‘slavers’ - Melbourne Indian couple who kept a grandmother as slave for eight years jailed for 'crime against humanity' - By Danny Tran. Posted Wed 21 Jul 2021 at 2:45pmWednesday 21 Jul 2021 at 2:45pm, updated Wed 21 Jul 2021 at 11:06pm. Source

Colonisation and Dispossession - Truth-Telling Works Both Ways

City of Moreland – a welcoming city for newly arrived migrants and refugees

Moreland Council promotes respect for diversity of cultures, religions, and languages. We celebrate the benefits migrant and refugee communities bring to Moreland. - Moreland Council website

The residents of Moreland overwhelmingly agree with Australia’s migration program which involves settling New Australians into our country. This is an extension of the historical process of colonisation and settlement. Even the councillors who advocate for the changing of Moreland’s name welcome migrants and refugees to our Municipality.

We would not have wonderful cities today, like Melbourne, if settlers like Dr Farquahar McCrae had not migrated here and started farms, businesses and homes.

Figure 26 - Melbourne in 1838 painted (apparently from a model) by Clarence Woodhouse (1852-1931). Flagstaff Hill (possibly exaggerated) is in the upper left of the picture (With Moreland in the distance behind). (State Library of Victoria). Source

Figure 27 - Melbourne today in 2022 - one of the world’s greatest cities. Home to 5 million people. Built on colonisation and migration. Source

We should not be made to feel guilty about the ‘dispossession’ of Aboriginal people - it is very sad that it happened, but great migrations are part of the history of mankind. Even Aboriginal societies dispossessed their neighbouring Aboriginal tribes.

Consider the case of Senator Lidia Thorpe’s own Aboriginal tribe, the Gunnai/Kurnai who attacked and massacred and dispossessed 77 Bunnurong Aboriginal men, women and children down on the Nepean Hwy at Brighton in the early 1830’s., only a few tears before Dr Farquahar McCrae arrived in Moreland.

This is the tragedy of mankind - all our societies have committed dispossession in the past. It is very unfair for people like Senator Lidia Thorpe to only attack the settlers of Moreland like Farquahar McCrae when her own ancestors were no better.

Below is the report from the historical record of the Warrowen Massacre of Brighton, one of the largest massacres in recorded Australian history.

This massacre was carried out by Senator Thorpe’s ancestors. It is so well known that it has its own Wikipedia page.

Figure 28 - Senator Lidia is a Gunnai [Kurnai] Aboriginal woman.

Figure… Senator Lidia Thorpe supports the name change of the Moreland municipality and supports ‘decolonistion.’

The main sources for the [Warrowen] massacre are the letters of William Thomas, the Assistant Protector of Aborigines of Port Phillip. In an 1840 letter to Superintendent Charles La Trobe, he wrote that "about four years ago 77 people were killed at Little Brighton not nine miles from Melbourne". The letter listed "events in which the Bonurong had suffered at the hands of the Kurnai", in order to "explain to La Trobe the deadly enmity that had existed for a very long time between the Bonurong and their eastern neighbours". He further explained that he had "known about these historic events almost from when he arrived in Melbourne, and that they formed part of the Bonurong singing".

In a later report in 1849, Thomas recorded that:

[the] blacks remember the awful affair at Warrowen (place of sorrow) near where Brighton now stands, where in 1834 nearly a quarter of the Western Port blacks were massacred by the Gippsland blacks who stole up on them before dawn of day."

Thomas gave further detail of the massacre in his description of an incised tree in a paper on Aboriginal monuments and inscriptions:

[They have] no monuments whatever further than devices on trees where any great calamity have befallen them. On a large gum tree in Brighton, on the estate of Mr McMillan was a host of blacks lying as dead carved on the trunk for a yard or two up. The spot was called Woorroowen or incessant weeping. Near this spot in the year 1833 or 4, the Gippsland blacks stole at night upon the Western Port or Coast tribe and killed 60 or 70 of them.

While passing through Gippsland in 1844, George Augustus Robinson wrote in his diaries that "the natives of Gippsland have killed 70 of the Boongerong [Bunurong] at Brighton". His informant was Munmunginna (transcribed by Robinson as "Mun mun jin ind"), whose father was from the Yowengerre clan.

According to Fels (2011), the massacre was "well known to early settlers, is mentioned in histories of Brighton, and pioneers' accounts – it was commonplace information in early Melbourne history"

- Marie Fels, 'I Succeeded Once' - The Aboriginal Protectorate on the Mornington Peninsula, 1839–1840, ANU pp255 - here

If “Moreland” is such a bad name, what about “Deakin” University?

Figure 29 - Dr James Lesh the writer of the report on the “Moreland” name. Source

To some observers, the choice of Council to engage Deakin University to undertake an historical review of the name ‘Moreland’ and its alleged links to slavery and racism appears to be ‘problematic’.

This is because the Deakin University itself is named after a man that many today would find has unacceptable racist leagacies.

Alfred Deakin, after whom Dr Lesh’s University is named had much stronger views on Aboriginal people than Dr Farquhar McCrae ever expressed.

In January 1901, the London Morning Post newspaper published ‘The Australian Union’, the first piece from its new ‘Special Correspondent’. The article offered the Post’s readers an intimate, engaging and remarkably well informed commentary on Australia on the eve of Federation.

The anonymous correspondent was Alfred Deakin who had, only two days before the article’s publication, been appointed the first Attorney-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. A leading federalist, Deakin dominated national politics until 1910, serving as Prime Minister no less than three times (September 1903–April 1904, July 1905–November 1908 and June 1909–April 1910) before finally leaving politics in May 1913. Throughout this period, he continued to write as the Morning Post’s correspondent on Australian affairs, offering purportedly ‘frank commentaries … on Australian politics and politicians, including himself’ (Source).

Consider the following published article (abridged) by Alfred Deakin and decide for yourself if Moreland City Council should have paid a University named after a man with the self-confessed ‘racist’ legacies of Deakin, to procure a report from Deakin University that only alleges the Moreland was named after a long defunct slave plantation.

There is no proof that Dr Farquhar McCrae himself named ‘Moreland” after the slave plantation, whereas Deakin University celebrates its name after what we would consider today to be a ‘self-confessed racist’.

Figure 30 - Alfred Deakin c.1901, after whom Deakin University was named.

National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an23302919

SYDNEY, Oct. 8 1901, AUSTRALIA’S PEOPLE. WHITE LABOUR MOVEMENT.

THE NEW LEGISLATION. FROM OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT [Acutally Alfred Deakin the Father of Deakin University]

Little more than a hundred years ago Australia was a Dark Continent in every sense of the term. There was not a white man within its borders. Its sparse native population was black as ebony. There are now some sixty thousand of their descendants remaining and about eighty thousand coloured aliens added. In another century the probability is that Australia will be a White Continent with not a black or even dark skin among its inhabitants. The Aboriginal race has died out in the South and is dying fast in the North and West even where most gently treated.

Other races are to be excluded by legislation if they are tinted in any degree. The yellow, the brown, and the copper-coloured are to be forbidden to land anywhere… A handful of British with little more than nominal occupation of half the continent is so stubbornly British in sentiment that it proposes to tolerate nothing within its dominion that is not British in character and constitution or capable of becoming Anglicised without delay. For all outside that charmed circle the policy is that of the closed door.

NO TRUCE WITH THE COLOURED MAN.

…Those Chinese, Japanese, or coolies who have come here under the law, or in spite of it, are not to be permitted to increase. As the successful among them invariably return to their native lands, a stoppage of reinforcements means the extinction in one generation of this alien element in our midst.

The Kanakas brought to our shores under statutory authority are to come no more after 1903, and are to be banished after 1906…This amendment, accepted by Mr. Barton in the House and carried somewhat unexpectedly, was fiercely attacked in the Senate by the Free Trade Opposition and the Conservative Ministerialists in combination. The contest was prolonged and severe, but with the solid support of the Labour section the Government triumphed by narrow majorities on every division. This is surely the high-water mark of racial exclusiveness…

The first important Acts placed on the statute-book by the Federal Parliament will be those relating to aliens and South Sea islanders, both inspired by the national ideal of a White Australia….

-Deakin’s Letters to the Morning Post, [our emphasis, Full text here: Australian Parliamentary Library]

The second problematic issue we have identified is Dr Lesh’s very unfair and hypocritical, in our opinion, slur on Dr Farquhar MacCrae’s support for the migration of Indian workers to Australia.

We note that this request by McCrae was not granted by colonial Governor Gipps or the British Government, so no Indians were brought to Australia.

For example Dr Lesh in his reports casts a slur on the McCrae family with him comments,

‘Farquhar was noted in colonial records for his support of bringing 'Indian coolie labour' to the Australian colonies’ (Ref 1. p2.) and

‘Firstly, to assist with improving his property estate, in response to widespread labour shortages, Farquhar signed a popular petition in 1842 to bring ‘Indian coolie labour’ to the Australian colonies, which was ultimately rejected by authorities’. (Ref. 1,p11)The above is the first of the ‘problematic’ issues in this sage of the name change - if the name ‘Moreland’ is deemed to be offensive because of its alleged racist legacies, why isn’t there a likewise call to change the name of Deakin University give the proven racist legacies of its namesake, Alfred Deakin?

This contrasts with Dr Lesh’s employer, Deakin University, who have been active in the Indian market for 25 years bringing Indians to Australia to study and work, as we learn from Deakin University’s webpage:

Figure - Just like Dr Farquhar McCrae wanted to use Indian workers in his business. McCrae failed to import even one Indian, Deakin Uni was spectacularly sucesseful with its ‘coolie student trade’ as Austrade tells us : Deakin University shows how long-term investment in India pays dividends, January 2020

Figure 31 - Deakin University’s Indian sub-continent committment to sourcing Indian Students & Workers for Victoria. Source

Figure 32 - More than 5,300 Indian ‘coolie students’ are at Deakin University in any one year, a certain proportion of whom are only here for the work and residency opportunities - the ‘workplace initiatives and industry placements’ referred to by Deakin. (Source)

It seems highly unfair and even hypocritical to the casual observer that the ratepayers of Moreland are being asked to carry the multi-million dollar expense of a name change because a man who lived on a property called Moreland nearly 200 years ago tried, but failed, to bring even one Indian worker to Australia.

This compares to Moreland City Council nowadays which welcomes immigrants and refugees from India with open arms - see Moreland Council website

Deakin University Wage Thefts?

Allegations of wage-theft have been levelled at Deakin University in recent times. To our knowledge Dr Farquhar McCrae did not ‘steal wages’ from his employees at Moreland.

Figure 33 - Deakin University has recently been accused of ‘wage theft’.