The Frontier Wars - Myth or Reality?

This Post is Being regularly Updated. Items will be added - both in support of the “Frontier War” Thesis and Against it - on a semi regular basis. Notifications of new additions will be noted here:

1 - 8/11/25: Aborigines in Sydney Cove avoided the redcoats (soldiers) - See here

2 - 8/11/25: The 1933 Cambridge History that the Aborigines were not Warlike - See here

3 - 11/11/25: images of frontier conflicts - See here

4 - 12/11/25: Some original instructions/guidance/understanding that supports the idea that the British viewed the Natives as being equivalent to the settlers with regard to responses by the ‘Military Force’

“One specific question has, however, recently arisen on this Subject [the treatment of the Natives], which seems to require a decision. It is whether the Governor may oppose, by Military Force, incursions of the Natives, when made in a predatory and hostile manner. My own opinion is that no real distinction is to be made, in this respect, between the the Natives and the settlers; but that the same methods may lawfully be taken to repress outrage and Riot, whether the Aggressors are of the European or of the Aboriginal race.” - pdf file. here Item IX and source HRA S IV, v1, p611

The above is an excerpt from an 1825 advice by Mr James Stephen [1789-1859] later Sir James Stephen Undersecretary of State for the Colonies.

Figure (i) - HRA S IV, v1, p591

What the above suggests is that affrays, conflicts, battles, uprisings by the Aborigines against the settlers or government forces were in Stephen’s opinion to be viewed as ‘outrage and riot’ not ‘war’ . This is exactly the same reasoning to explain why the uprisings/riots of the Eureka Stockade/Rebellion and Castle Hill are not included in Canberra’s War Memorial - they were civil disturbances between British subjects not ‘war’ despite the fact that British Military forces were used.

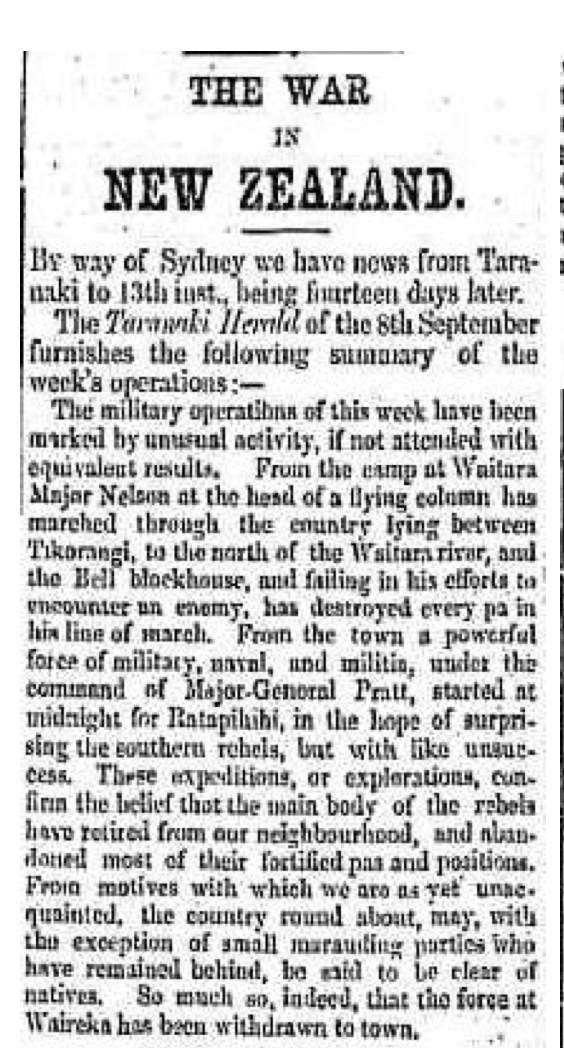

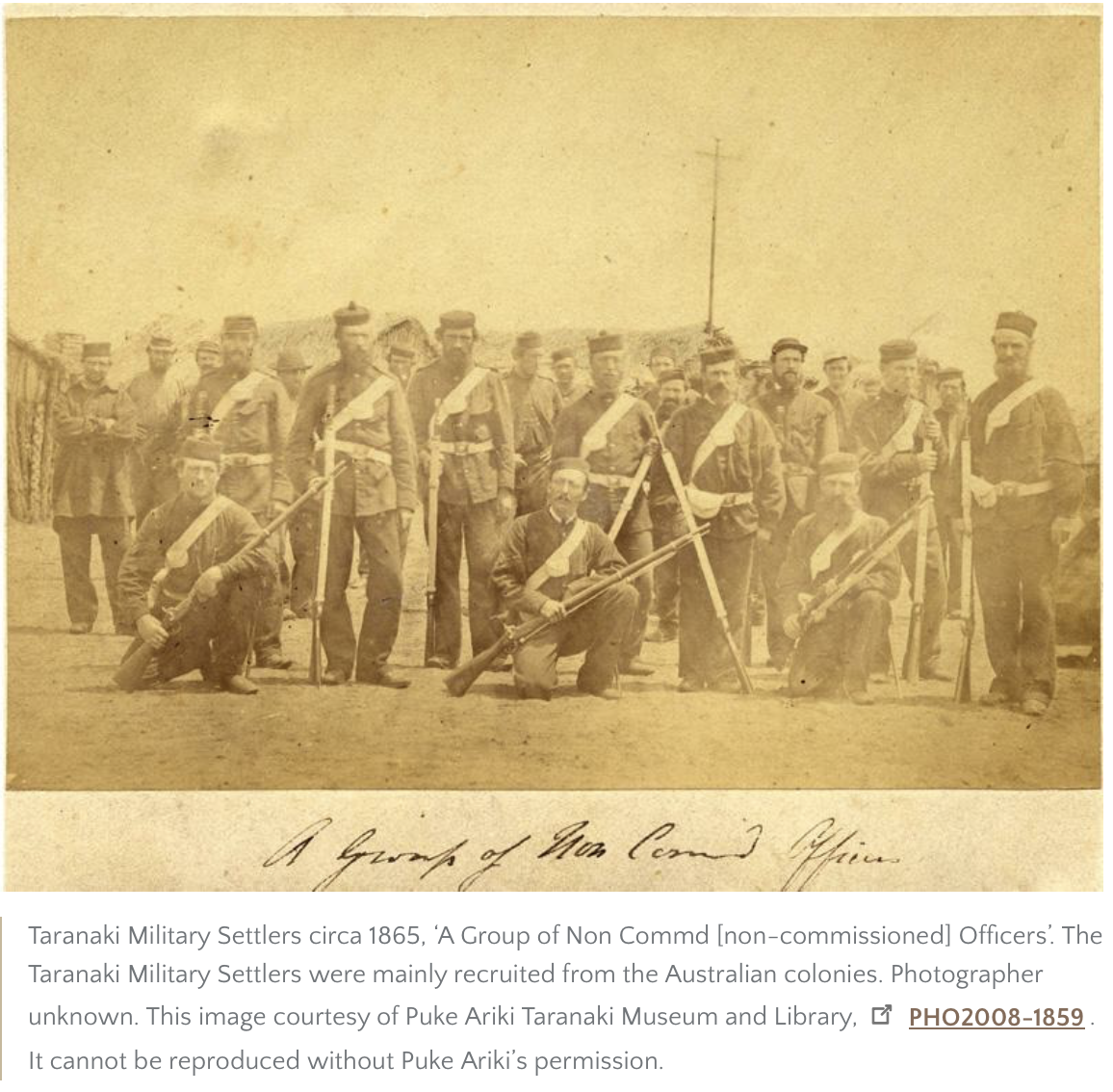

5 - 4/1/2026 - Declarations of “War” against the Maori in New Zealand in 1860.

Are there similar newspaper reports of formal “war” to be found in the so-called Frontier Wars against the Aborigines? Please email with any examples you can find.

Figure A - Source: Geelong Advertiser , Tuesday 25 September 1860, page 3. Full pdf here - Trove

6 - 6/1/2026 - Some examples of the use of the word “war” in Australia, in the context of fighting with Aborigines, are available: here

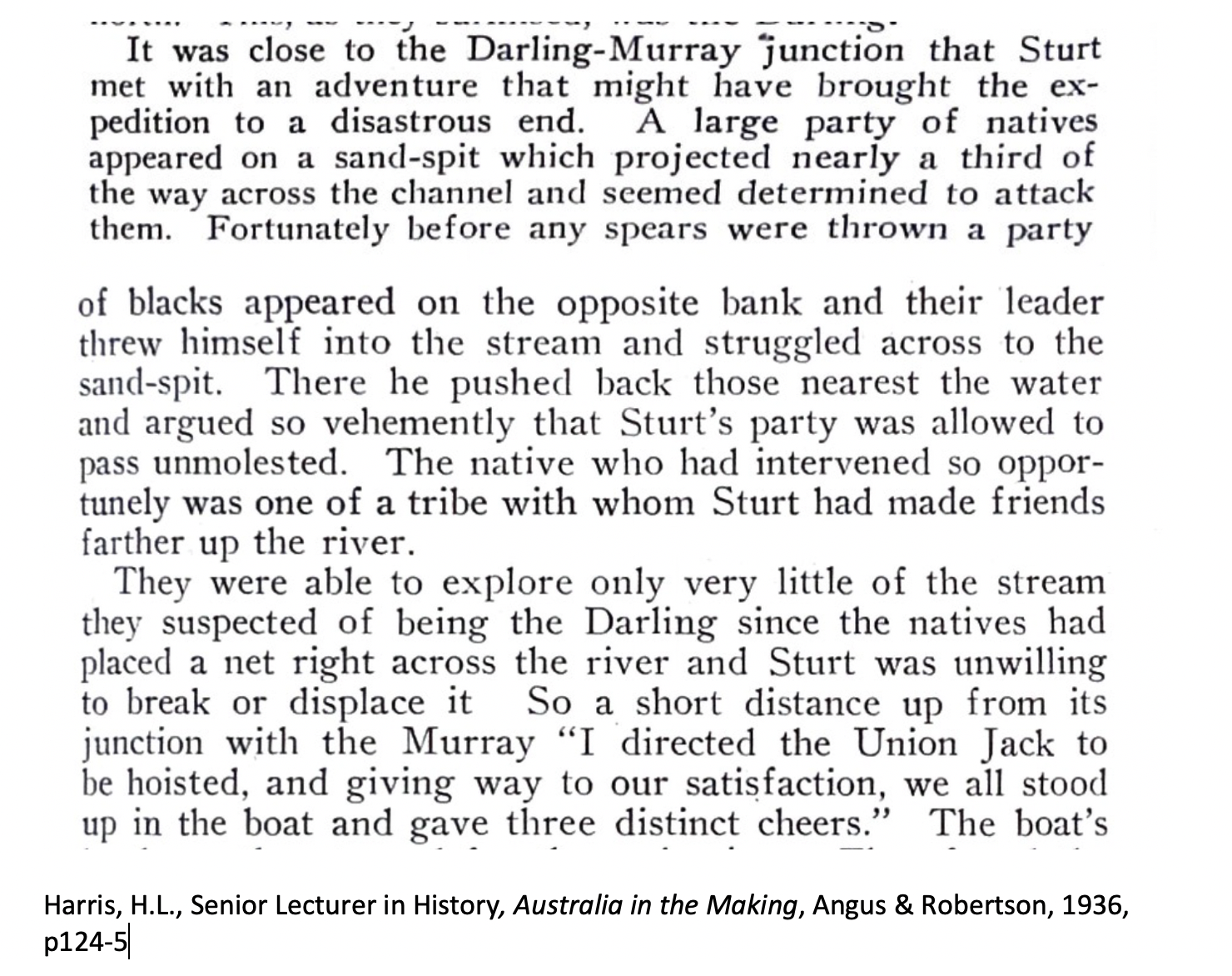

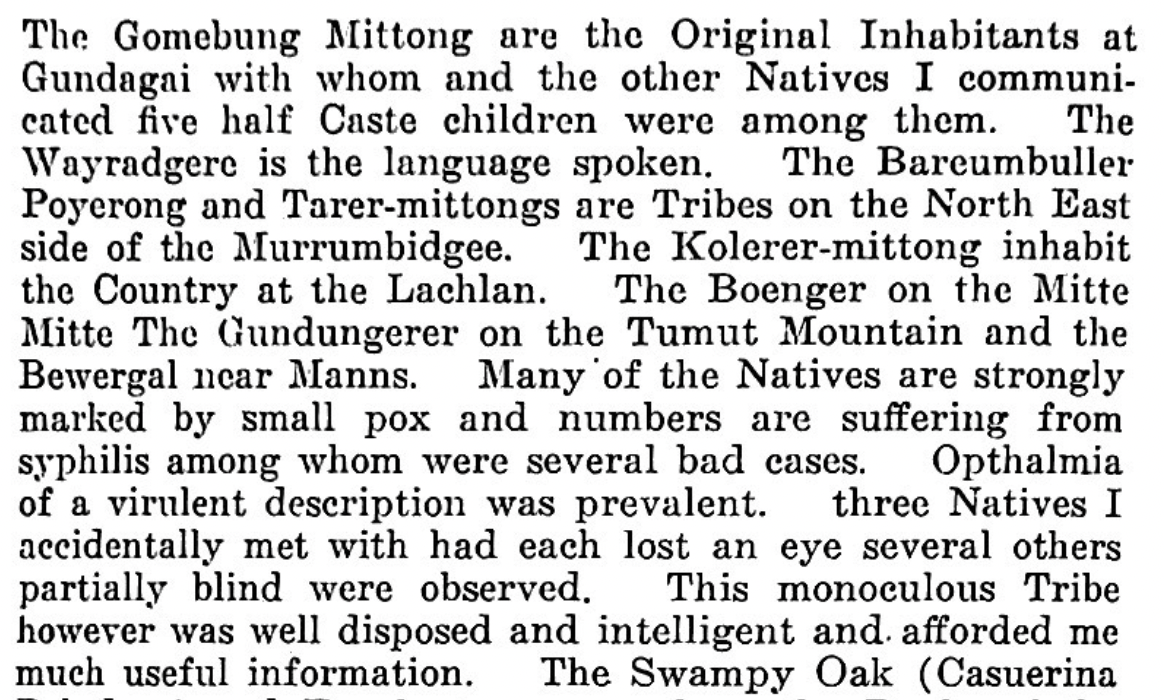

7 - 6/1/2026 - If there was a `Frontier War’ raging, why were there reported cases of friendly Aborigines defusing conflicts with settlers or, as in this case, the explorer Sturt in 1829? Was there a general ‘uprising’ or not?

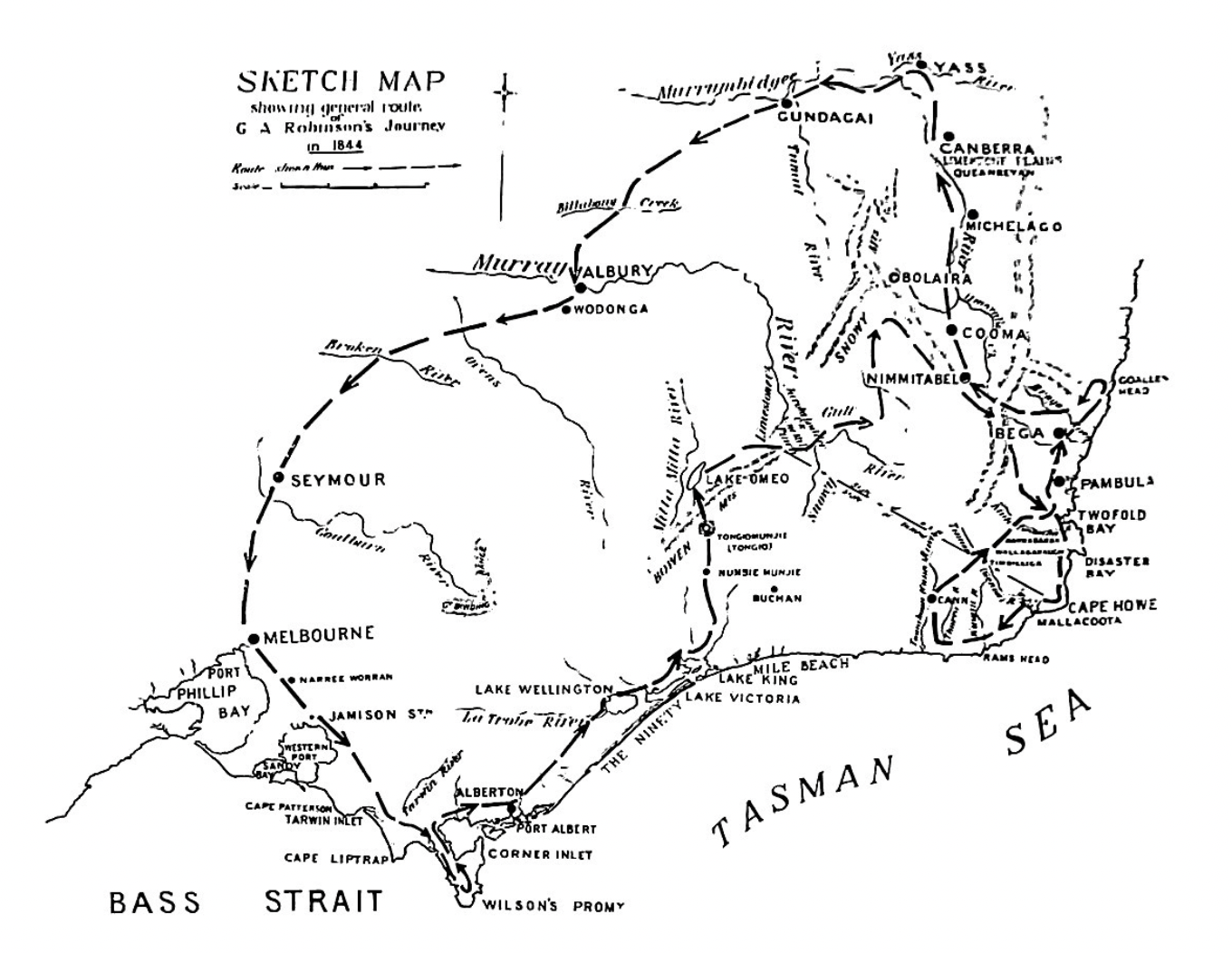

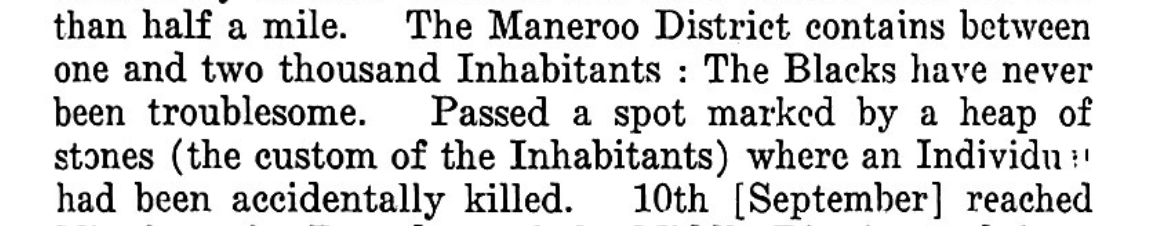

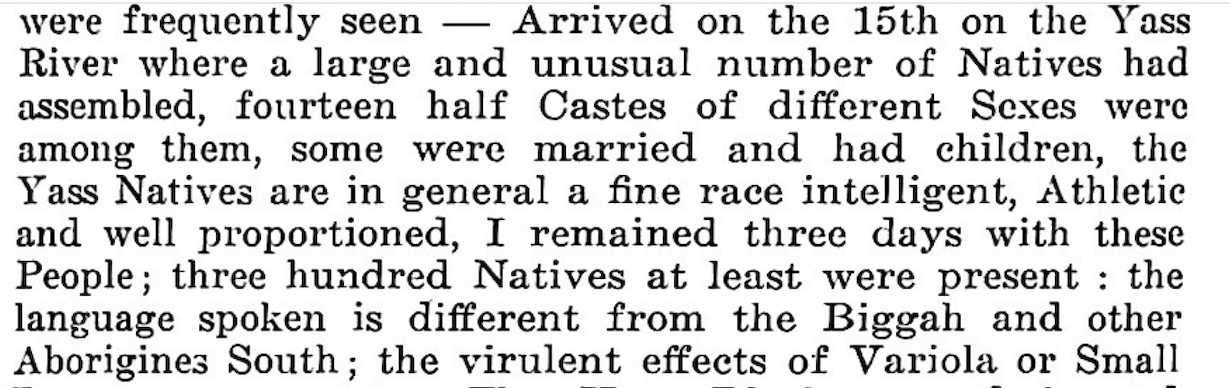

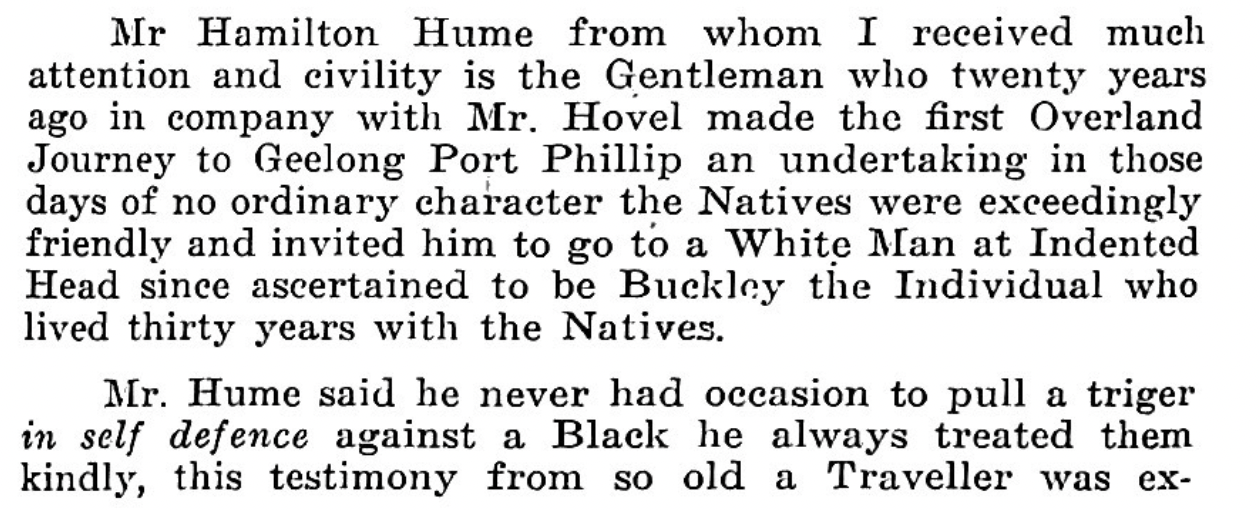

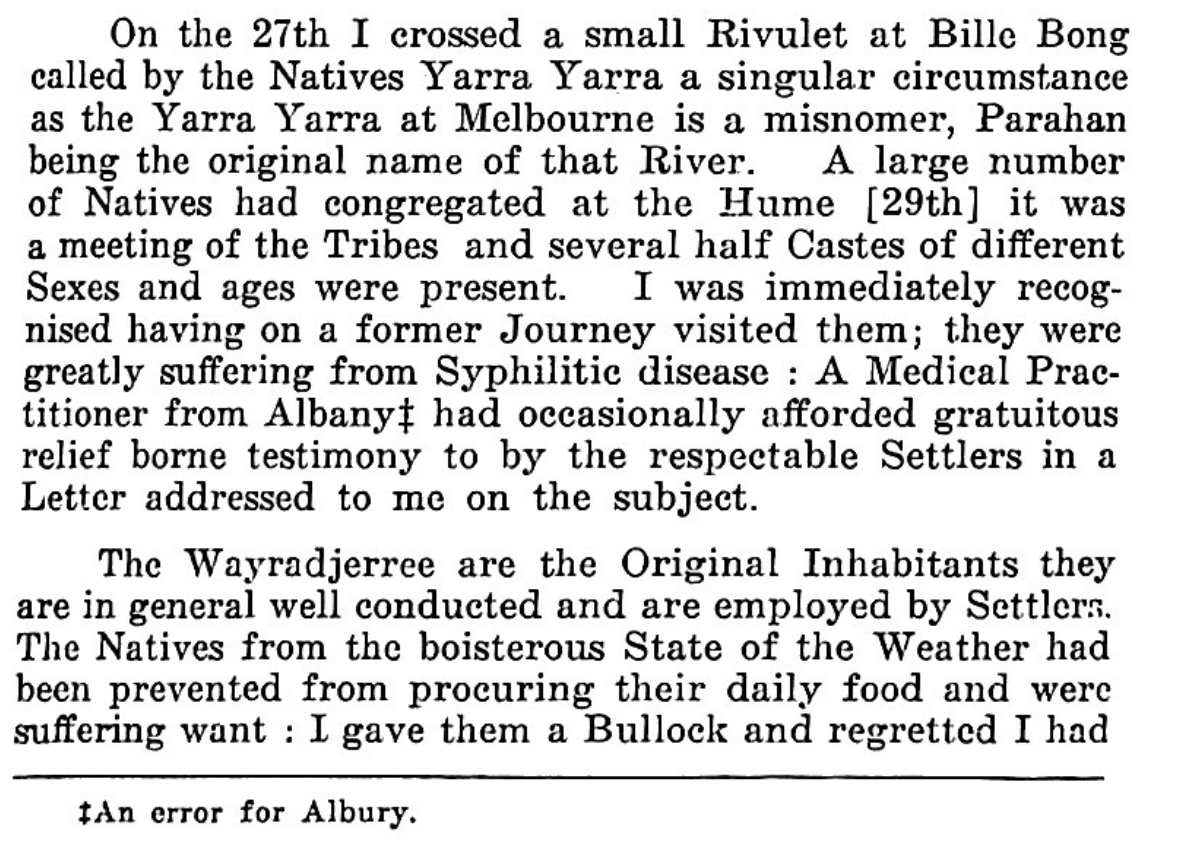

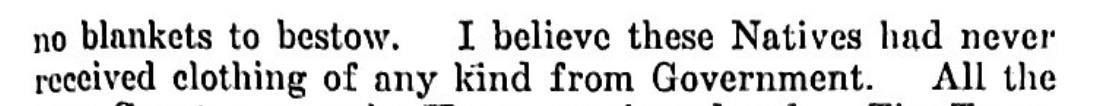

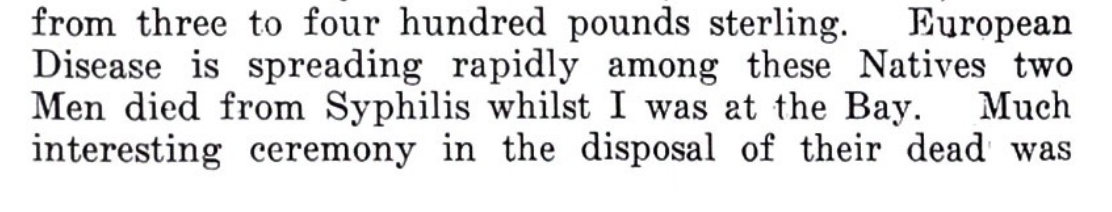

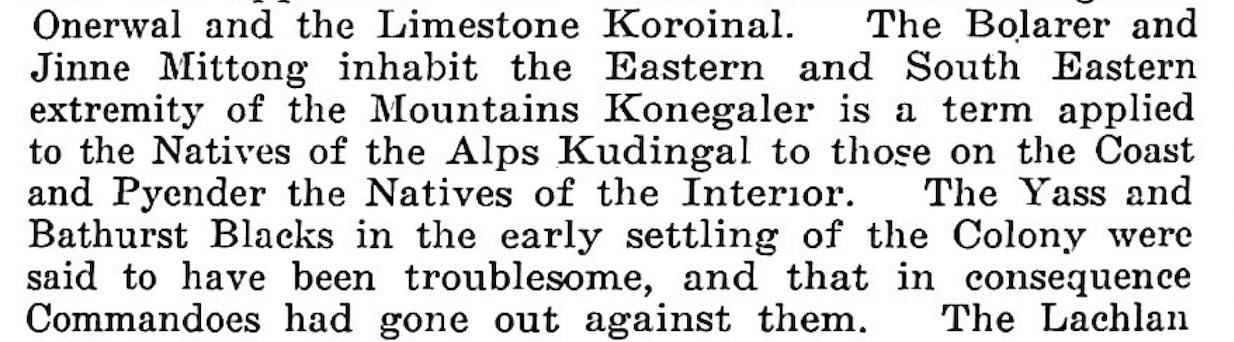

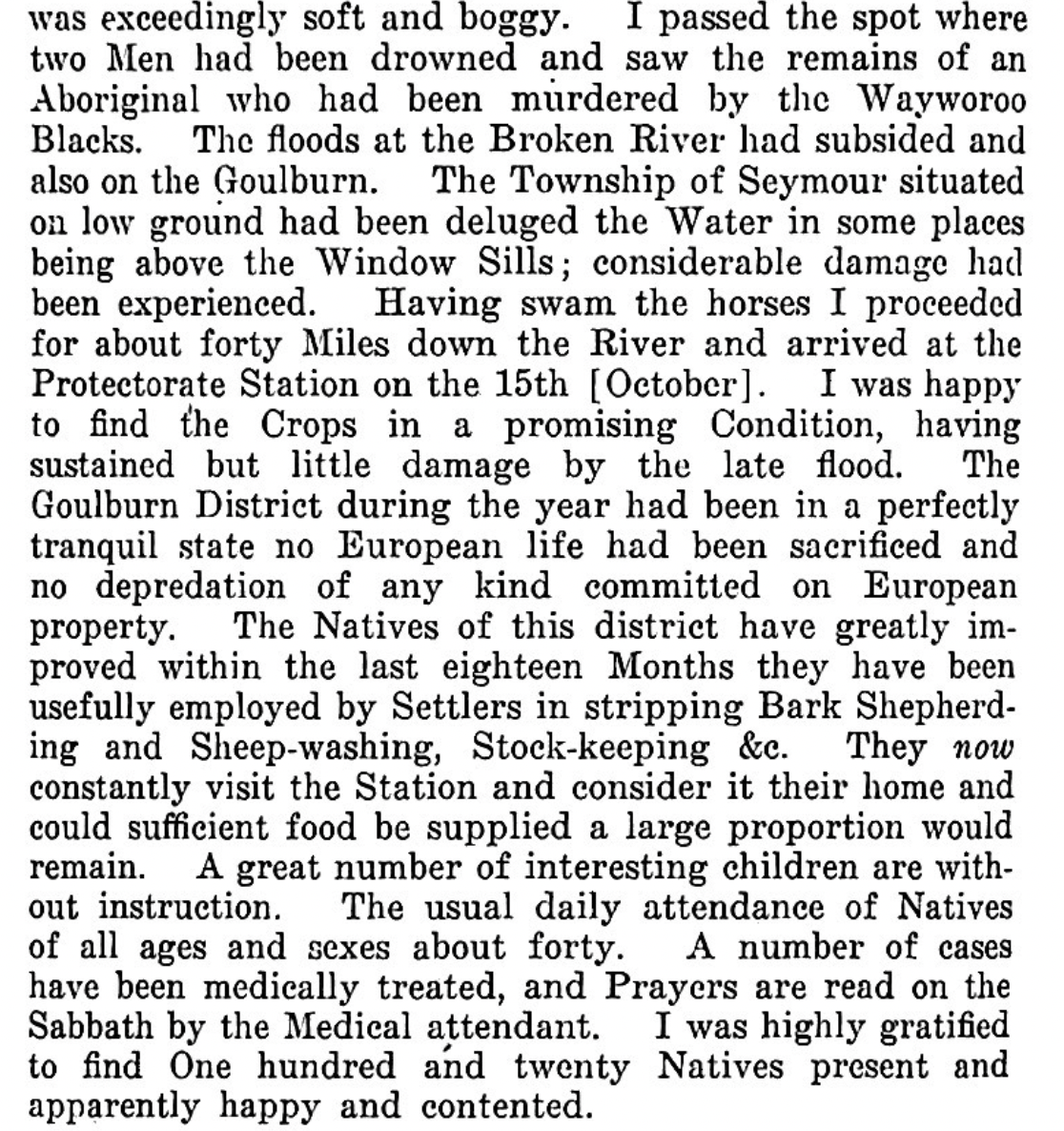

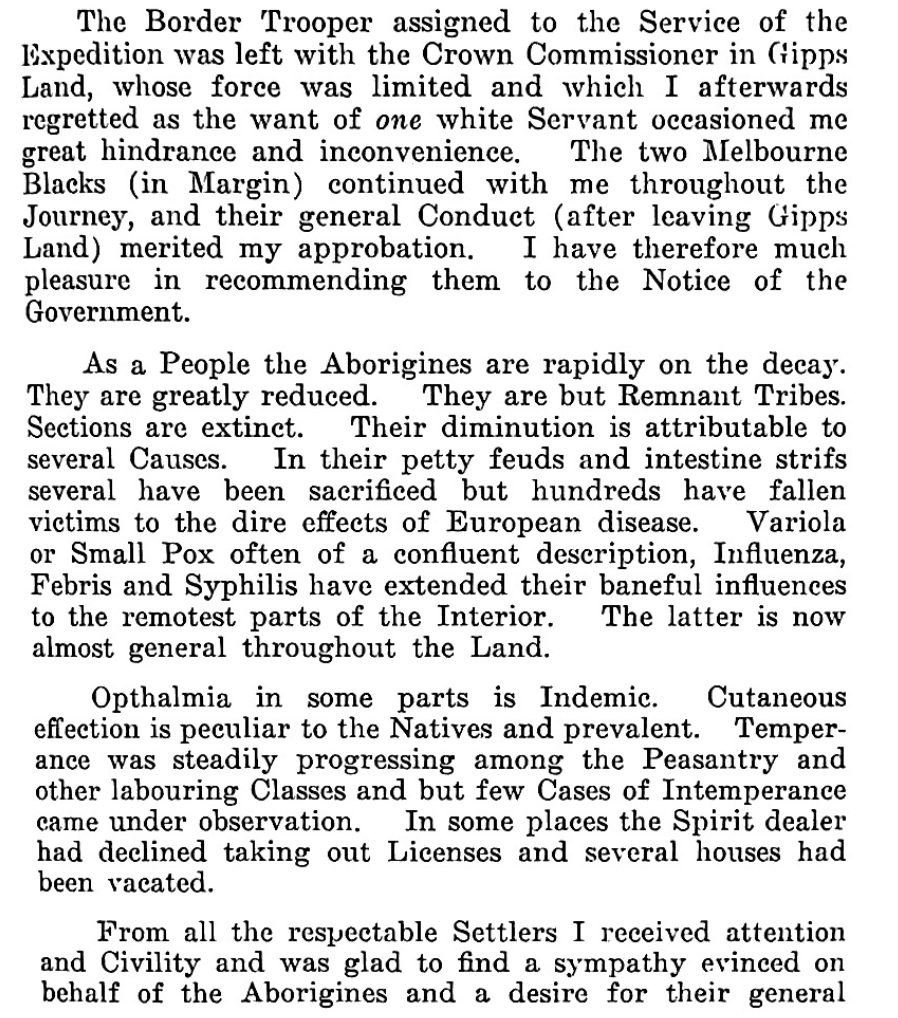

8 - 7/1/2026 - The following Figures B are selected journal entries from, George Augustus Robinson’s Journey into South-Eastern Australia - 1844, [George Mackaness (ed), Australian Historical Monographs, Vol XIX (New Series) p8-35: full pages 8-21 here and full pages 22-25 here ] regarding the Aborigines from SE Australia.

The extracts indicate:

that race -relations were not always violent between the Aborigines and the settlers - there wasn’t necessarily a raging ‘frontier war’ always everywhere;

disease (small pox, influenza and syphilus) appears to have been a major contributor to the rapid reduction in the Aboriginal population, not necessarily detahs by so-called “war”;

that frequently the Aborigines were not ‘warlike’; they were peaceable and willingly came into the new settler society as willing workers, guides, policemen, stockmen, etc

there was unauthorised killing of Aborigines as reprisals for the killing of settlers. However Robinson also records as frequently inter-tribal killings and massacres by the Aborigines themselves.

Figure B1 - Sketch map of GA Robinsons 1844 journey of six months and seven days. Source: George Augustus Robinson’s Journey into South-Eastern Australia - 1844, [ Australian Historical Monographs, Vol XIX (New Series) p4 - 35 .

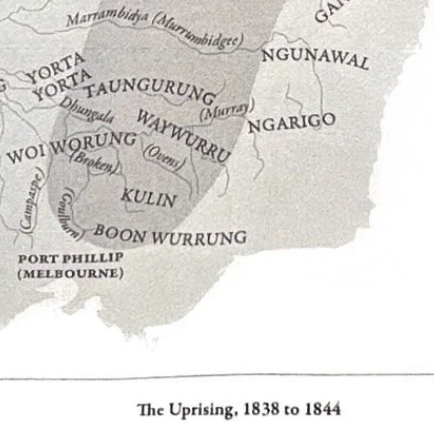

Figure B1A - Excerpt from Figure 22 below: A map of the supposedly six-year “uprising" , presented in a classical Western “war-campaign” format, that misleads the reader into thinking the Aboriginal tribes were working in a co-ordinated way from a central “war-room”. Source: Stephen Gapps, Uprising, War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838–1844, April 2025

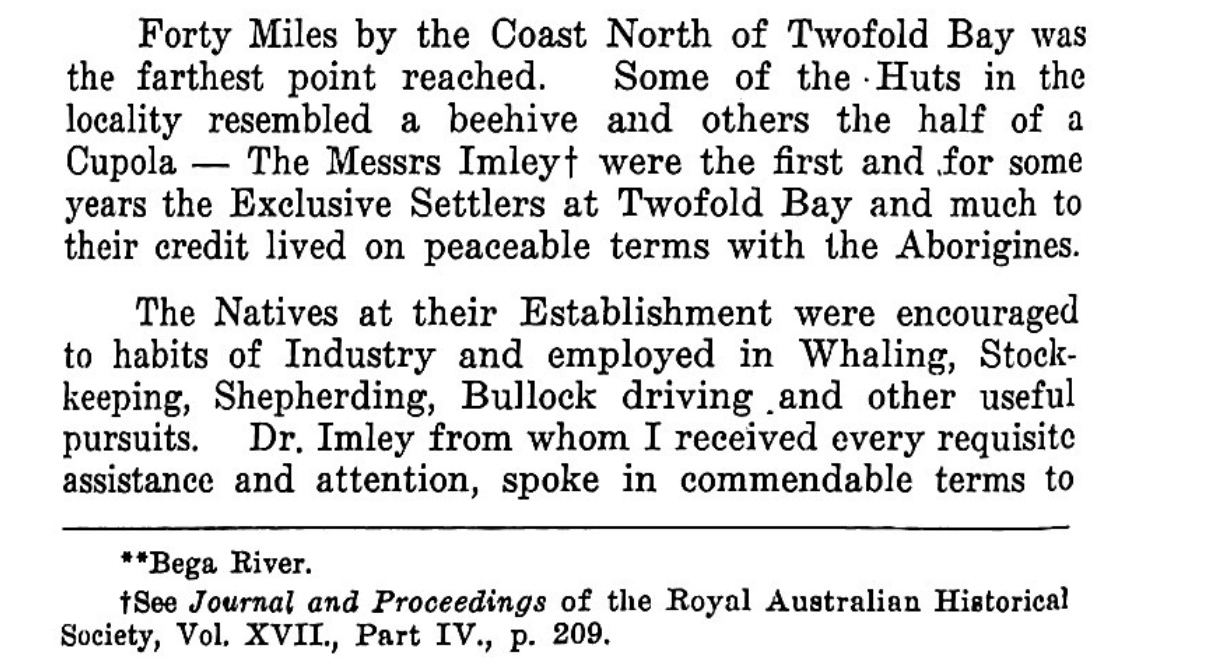

In 1844, Robinson found the Aborigines in these districts living `on peaceable terms’ with the settlers:

Figure B2 - ibid., p22

Figure B3 - ibid., p23

Figure B4 - ibid., p25

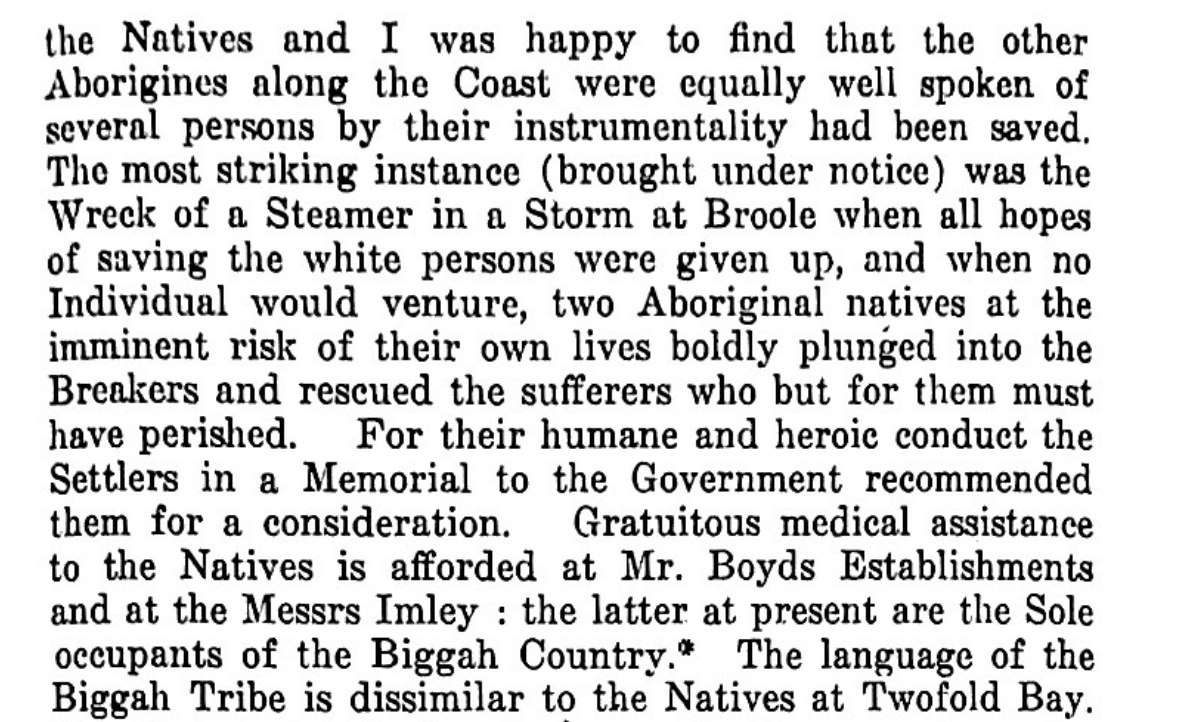

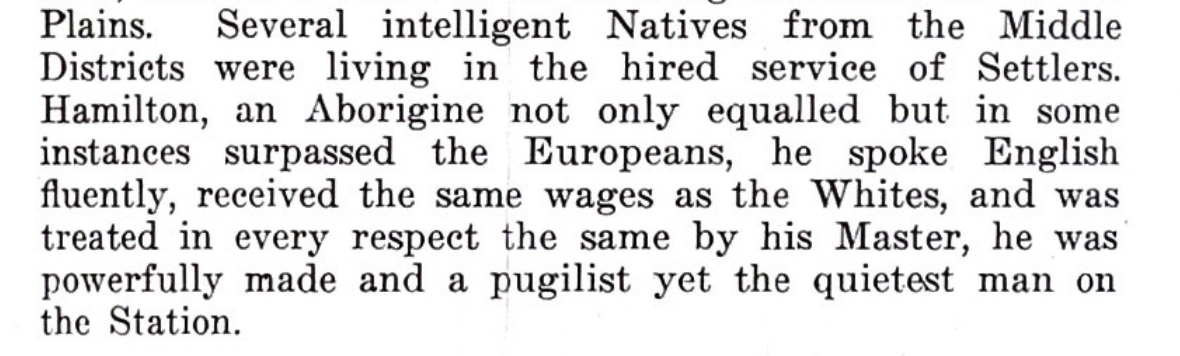

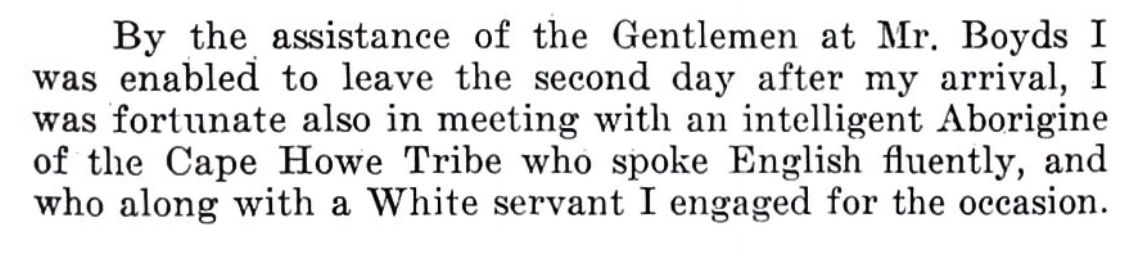

Many instances are recorded where the Aborigines exercised their agency and ‘came in’ to the settler society by learning English and gaining employment, even at equal wages as Robinson noted:

Figure B5 - ibid., p12

Figure B6 - ibid., p15

Figure B7 - ibid., p19

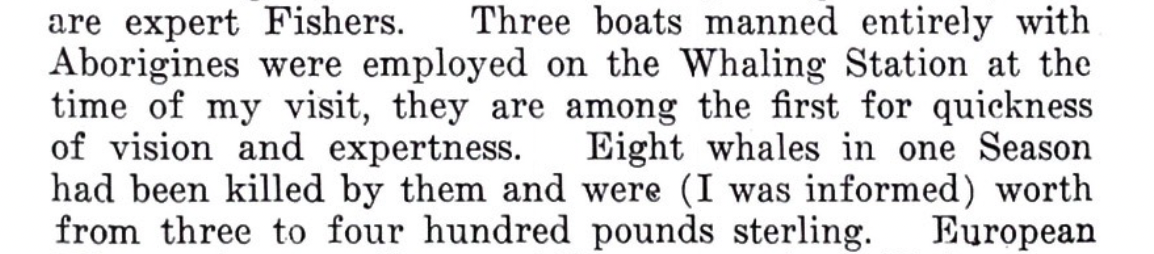

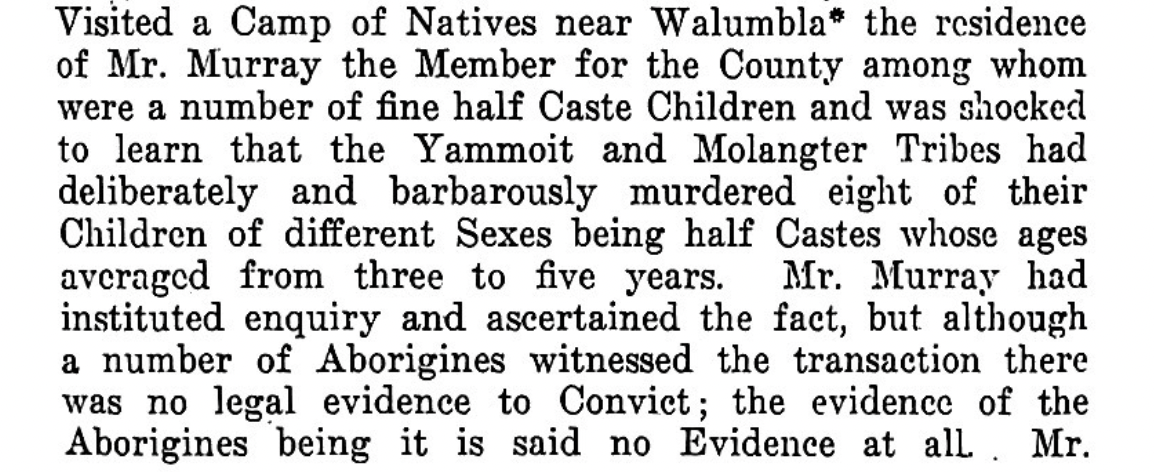

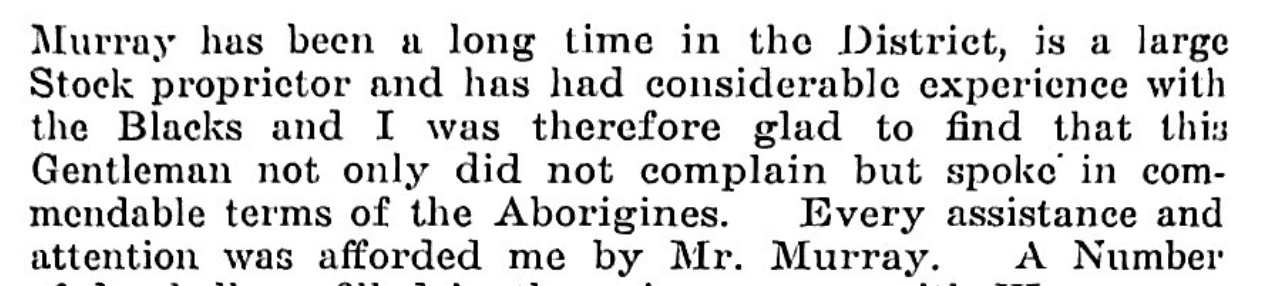

Robertson also began to notice the move toward reconciliation illustrated by the increase in inter-marriage between the Aborigines and the white settlers: the number of half-caste children was increasing despite the fact that some tribes were slower to modernise and accept cross-racial progeny by killing their half castes. Ultimately this practice would cease as tribes became less racist and less shamed by the occurrence of half-castes.

Figure B8 - ibid., p25

Figure B9 - ibid., p26

Figure B10 - ibid., p26

Figure B12 - ibid., p26

Figure B13 - ibid., p27

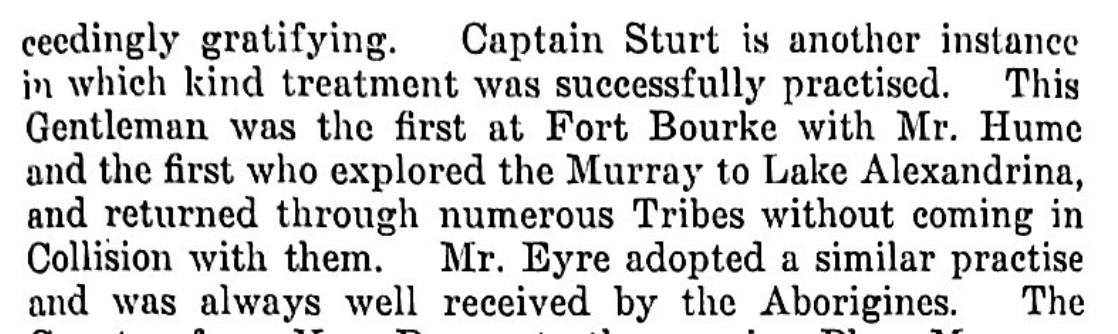

Robinson records several cases of ‘pox-marked’ Aborigines indicating that small-pox (or perhaps something similar) had ravaged the tribes within the past generation. Other diseases were also noted:

Figure B14 - ibid., p28

Figure B15 - ibid., p28

Figure B16 - ibid., p29

Figure B17 - ibid., p19

Robinson notes evidence that some tribes were very violent, not only to the settlers but also with other Aboriginal tribes. Some ‘commando’ reprisals were conducted by the settlers but these would not have been officially sanctioned by the government as ‘war’:

Figure B17 - ibid., p26

Figure B18 - ibid., p30

Figure B14 - ibid., p33

Figure B15 - ibid., p34

9 - 19/1/2026 - Some government despatches of c1852 described many examples of some of the Aborigines not being violent or “warlike”. Rather these despatches contain many examples of the Aborigines voluntarily working on farms and as stockmen and shepherds - see here and here

10 - 19/1/2026 - How the Aborigines appeared to the WA Colonial government is an 1837 despatch here

11 - 2/2/2026 - If there was a `Frontier War’ raging between the Aborigines and the British why weren’t there many examples of raids to steal/kidnap Aborigines on the one side and settler’s, their women & children on the other followed by ‘treaty’ negotiations for their release as occurred on say the American frontier? See Chapters VI, VII & VIII from Mary Maverick’s memoirs. Australia seemed to just have criminal-style conflict based around theft of property, stock, hunting grounds rather than militarily-style raids and treaty negotiations for the return of captives. See also the memoirs of Rachel Plummer.

Posted 25 October 2025

This long post is in response to email correspondence we have had, and continue to have, with several proponents, and their critics, of the “Frontier War” thesis.

I will lay out here much of the background to this thesis and hope ultimately to publish a book or series of papers on the topic in a much better written format.

In particular, the focus of this post is on some of the concerns that critics of this theory have raised. I don’t want to set the scene for a heated debate but rather promote a ‘conversation’ between the two camps by listing, in no particular order, all the problems that critics claim this theory poses.

On the one side of the conversation are the historians, commentators and activists who would have us believe that colonial Australia was settled violently, by a series of “wars” between the British and the various Aboriginal, so-called “nations”.

On the other side, their critics claim that the ``Frontier Wars” were a myth - there were officially no “wars” as such, as is commonly understood by the meaning of that word, during the settlement of Australia. Our country was not created by an invasion or conquest that necessitated “wars” between the British settlers and the native Aboriginal inhabitants.

Just by calling an event a “war” doesn’t make it one in any meaningful, legal or historical sense.

Rather, Australia was legally settled by occupation when internationally recognised sovereignty was established here by the British on 7 February 1788. This was actual date when the first governor, Arthur Phillip, was sworn in, his commissions and the proclamations read, and technically and legally the British “took possession of the colony in form”. Additionally, compared to the colonial settlements of other parts of the world such as New Zealand, Latin America, Southern Africa and North America, the settlement of Australia was relatively peaceful and of much lower, comparative violence.

1. Introduction

Strong and opposing views are held by many Australians when discussing the fighting, battles, killings and massacres that inevitably did occur during the British settlement of Australia.

The definitive prize for the proponents of the “Frontier Wars” thesis would be if the governing council for the Australian National War Memorial officially commemorated the ”wars” at Canberra’s National War Memorial. If the council had followed through with their reported 2022 statement that:

The War Memorial chair, former Howard government minister Brendan Nelson, revealed the Memorial’s governing council had decided they would have a “much broader, a much deeper depiction and presentation of the violence committed against Indigenous people, initially by British, then by pastoralists, then by police, and then by Aboriginal militia;

then this would have been a major win for the proponents of the “Frontier War” thesis.

It would have been case-closed on further conversation regarding our country’s foundation - Australia would henceforth be viewed as being not so much created as a “settlement by occupation”, but rather as by an “invasion”, and a “conquest”. The political outcome of this recognition by the Canderra War Memorial would be that these “wars” should have been concluded by a number of treaties that should have been entered into by the British with the “defeated enemy” , the various, so-called, Aboriginal “First Nations”.

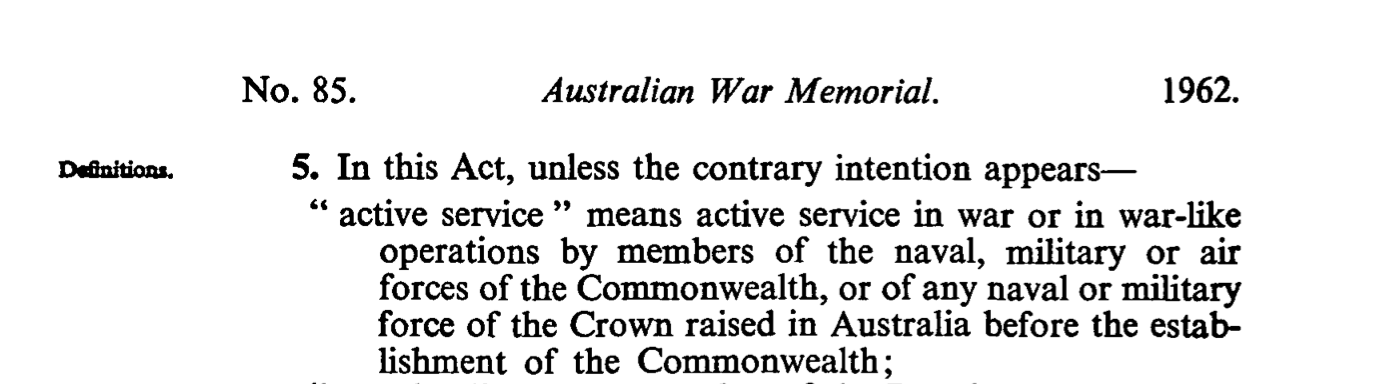

But the memorial’s council failed to follow through with their statement after intense lobbying against the proposal. Thus, the status quo continues - officially at the War Memorial the so-called “Frontier War” thesis is a myth, ostensibly because the governing council believes that these events did not constitute “war” or “war-like operations", nor were the participants in “active service” as defined under the founding Australian War Memorial Act 1962 (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 - A memorial only to those Australians who died under active service conditions. Source: Australian War Memorial Act 1962

Figure 2 - Frontier violence was between British subjects under one governing polity (the Crown and/or colonial governments). The events were not “war'“ between two sovereign entities. The events were rebellions. uprisings, burglaries, police operations, martial law campaigns, murders and sundry criminal activities. Source: Australian War Memorial Act 1962

Yet, the stakes continue to be high.

If the “Frontier War” theorists get the recognition they crave, then that opens the way for the activists to begin discussions on the payment of war reparations to the so-called, Aboriginal survivors and their descendants of the “Frontier Wars” [along similar lines to the payments and land grants now being made to various Aborigines in Native Title, Stolen Wages and Stolen Generations class actions].

Additionally, other activists who want to pursue self-determination and sovereignty claims for Aboriginal people would have their case greatly strengthened given that no formal treaties were signed to conclude these so-called “wars”. This would involve the politically loaded, unfinished business that the activists would seek to monetise and gain politically from, as espoused unsuccessfully so far in the demands of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The above is a summary of the politics at stake if the “Frontier Wars” theory becomes recognised as fact.

2. The “Frontier War” Theorists

This part of the post is designed to introduce the main proponents of the “Frontier War” theory.

2.1 - Professor Henry Reynolds - The ‘Father’ of his so-named “Frontier War” Theory

Figure 3 - Professor Henry Reynolds, the originator of the violent ‘Frontier War Thesis’

Professor Reynold’s starts our conversation with his following summary:

“… the verdict is now beyond doubt. Frontier conflict was violent and universal, accompanying national life for 140 years. The death toll was almost certainly much higher than the 20,000 I suggested in the early 1980s. It seems entirely plausible that many more Aborigines were shot down in Queensland alone. Definitive accounting may always be out of our reach, but frontier deaths may rival those of the First World War.”

“…frontier fighting no matter what form it took had to be about the ownership and control of territory. It therefore had to be war and, because it was fought in Australia and about control of the continent, it was Australia’s most important war. For us it was, on any measure, far more consequential than the balance of power in Europe in the early twentieth century or the contemporaneous scramble to carve up the Ottoman Empire.

So, while we can understand the means by which settler Australians were able to duck questions of warfare, it was never a possibility for their Indigenous contemporaries. No matter how the fighting unfolded or how long it lasted there could be no avoidance of the true magnitude of the conflict. It was not just the forced cession of control over homelands but also the continuity of an entire way of life and even the physical survival of a people. It was an unparalleled catastrophe far beyond what Australian personnel have ever suffered in war no matter how severe.”

- Henry Reynolds (Reference 1 - at end of post)

Some of the “Frontier War” books that make up the thesis of Henry Reynolds include:

Figure 4 - The first book on the so-called Frontier War Thesis.

Figure 5 - One of many of Reynolds’ followup “war” book to support his ‘Frontier War Thesis’.

1981 - The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia

1989 - Dispossession: Black Australia and White Invaders

2000 - Why Weren't We Told?

2001 - An Indelible Stain? The Question of Genocide in Australia's History

2003 - Forgotten War

2016 - Unnecessary Wars

2021 - Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader & Tasmanian War Hero. With Nicholas Clements

As far as we are aware, Reynolds has never gone as far as to use the “G-word” - “genocide” - when describing the frontier conflicts and the settlement of Australia. Although he believes the outcome was devastating in terms of loss of Aboriginal lives and the destruction of Aboriginal societies, he does not believe it was an official, deliberate or systematic policy of the British to extirpate the Aborigines, as would be a requirement under a definition of genocide.

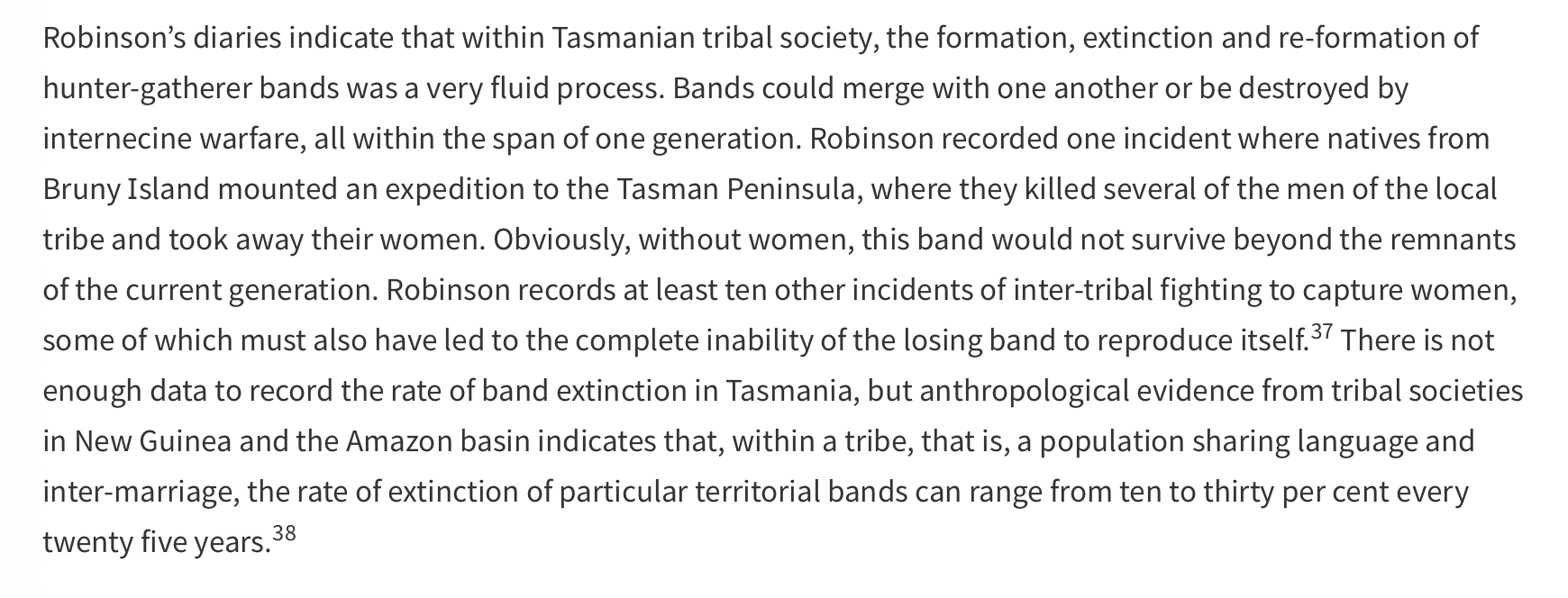

2.2 - The Late Professor Lyndall Ryan - Historian, supporter of Henry Reynolds’ Thesis and Originator of the Colonial Frontier Massacre Map at the University of Newcastle.

Figure 6 - The late Professor Lyndall Ryan historian and creator of the Colonial Frontier Massacre Map at University of Newcastle.

“[Historian Henry] Reynolds' work is based on three abiding themes: a strong internationalism drawn from the United Nations Charter on Human Rights; that the ghost of racism underlies modern Australia; and indigenous issues and justice should be at the centre of public debate.”

- Lyndall Ryan (Reference 2)

Professor Ryan’s position on the “Frontier Wars” was more ‘extreme’ than Reynolds’. She was ‘happy’ to use the “G-word" - [see an extract of her co-authored paper - Dwyer, P., & Ryan, L. (2016). Reflections on genocide and settler-colonial violence. History Australia, 13(3), 335–350.]

She has also commented in the media on her view that genocide did occur in the founding of Australia:

“It’s a common thread that, whatever period of time, the Aborigines are not wanted. The settlers and the police are trying to eradicate them completely from the landscape,” she said before the launch of the [Colonial and Frontier Massacre Map] project’s second stage on Friday.

“I didn’t go into it expecting to find that. I’m not a genocide scholar, and I’ve actually published articles very recently saying that I didn’t think that genocide happened in Australia, and I’ve had to change my mind".

- Lyndall Ryan, Newcastle Herald 27 July, 2018

2.3 - Dr Stephen Gapps is a relatively new and hard-working entrant into the field who is ‘carrying the baton’ for the “Frontier War” thesis into the future.

Figure 6B - Dr Stephen Gapps. Source

He describes himself as, ‘an historian committed to bringing the Frontier Wars (1788-1930) into broader public recognition as Australia’s First Wars.’

Gapps is developing a series of books, each one seemingly making wider and bolder claims than the previous, backed up it is said with extensive footnotes and citations gleaned from the archives.

As with Henry Reynolds and his publishers, who notably emphasised the word “war” in the titles for his books, Gapps has continued this tradition - the word war appears in each of his book titles. However, he further energises the conversation with the use of what some would see as highly politicized words in the titles and throughtout his books - words such as “war of resistance”, “guerrilla” tactics and “uprising.”

From the get-go, Gapps is priming his readers for a journey of military history as violent as any documented about the Conquistadors, or what occurred in the American Indian, Maori or Zulu wars.

Gapps has also co-edited The Australian Wars, with Rachel Perkins, Mina Murray and Henry Reynolds (Figure 12). This book which has been acquired by Allen & Unwin in a world-wide distribution deal is based on the Rachel Perkins film, The Australian Wars (Figures 10 & 11).

Figure 7 - 2018

Figure 8 - 2021

Figure 9 - 2025

Stephen Gapps, Uprising, War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838–1844, 9781742238029 / April 2025

2.4 - Film Maker Rachel Perkins

Rachel Perkins, described as an ‘Arrernte and Kalkadoon filmmaker’, gave ‘a powerful National Press Club address’, accompanied by historian Professor Henry Reynolds, where they explored ‘the bloody battles fought on Australian soil and the war that preceded the Australian nation.

Drawing on research featured in the powerful new SBS television series The Australian Wars, they will share insights on conflicts and deaths across the continent amid fierce battles for land and survival.’ (Source and full Address - film clip excerpt below)

Figure 10 - Rachel Perkins, director of The Australian Wars, a 3-part documentary of 2022

Figure 11 - The Australian Wars, a 3-part documentary of 2022 - Trailer here

Figure 12 - Book of The Australian Wars

Perkins had already touched on the theme of the “Frontier Wars” in her earlier film, The First Australians, where one of the luminaries she relied upon to narrate her film was the 'fake’ Aboriginal man Bruce Pascoe (Figures 13, 14 & 15).

Many viewers were skeptical of this film’s claims and the fact that a ‘fake’ Aboriginal was put forward as a knowledgable Elder only added to their doubts - if Pascoe was faking his own ancestry, how could we trust his ‘scholarship’ and narration in Perkins’ film?

2.5 Institutional Response & Idea Laundering

Many observers believe that the “Frontier War” thesis is a myth, and nothing more than a lame, academic idea first developed principally by Professor Henry Reynolds within the 1970s academy, and then slowly brought to prominence over the decades due to the phenomenon of “idea laundering”.

Just like the laundering of ill-gotten money into socially acceptable funds, idea laundering involves the moving of false or misleading notions, ideas and information from unverifiable sources through increasing levels of respectability until, finally, they merge into the mainstream, where they were adopted as ‘fact’ and ‘knowledge’ and then further cited by reputable commentators.

The “idea” of the “Frontier Wars” is on such a trajectory now. After arising as a politically useful “de-colonisation” concept, with little supporting evidence, it has progressed through the university departments of Reynolds and Ryan, then been promoted out into the non-fiction book and film markets by, for example, Gapps and Perkins, and now is in the process of being accepted as ‘fact’ by the general media such as SBS (Figures 11&15) and ABC Four Corners (Figure 16) and round the world.

Figure 16 - ABC mainstream acceptance and free-advertising and promotion of the now well “laundered”, “Frontier War” thesis. Source ABC

2.6 - Dr Jack Clear - The Next Generation of “Frontier War” Theorists

On 6 December 2021, Macquarie University PhD candidate Jack Clear, submitted his thesis, entitled The Wiradjuri Wars: analysing the evolution of settler colonial violence in New South Wales, 1822-1841.

Figure 17 - Dr Jack Clear graduates with is PhD on The Wiradjuri Wars: Analysing the Evolution of Settler Colonial Violence in New South Wales, 1822-1841.

His thesis advances the claims of the “Frontier War” theory even further, making Clear part of the ‘third generation’ of emerging scholars in this now 50-year-old field.

Broadly, Clear’s contribution is to firstly reinforce Gapps’ scholarship by claiming that the first ‘bout of conflict…was fought in the Bathurst region from 1822 to 1824 and culminated in an infamous period of martial law [which]… has netted the ‘Bathurst War’ a significant degree of scholarly attention’ [by Gapps and others].

But the Clear then goes onto establish his own mark in the field of the “Frontier War” thesis by claiming:

“The second, and less well known, round of hostilities between the two peoples began thirteen years later in 1838. Centred on a collection of settlements on the Murrumbidgee River that would eventually coalesce into the town of Narrandera, this conflict brought armed Wiradjuri resistance to a bloody and tragic end at the Murdering Island massacre of 1841. Both the Bathurst War and its distant follow up-named in this study the ‘Narrandera War’- were examples of Anglo-Wiradjuri conflict.”… This thesis aims to … provid[e] a chronologically comprehensive overview of the Wiradjuri Wars from the outbreak of the first conflict in 1822 to the culmination of the second in 1841. With an emphasis on how the modes of war - that is, the means by which the Wiradjuri and the British fought one another - evolved during this time, it will be conducted as a study of military history. In addition, the analytical lens of settler colonial theory will also be used to contextualise the cause and effect of interracial violence as well as the operative logic behind the strategies and policies of the British belligerents. Through the intersection of these two historical disciplines the project also aims to contribute to the diversification of both military history and settler colonial studies.”

- Jack Clear PhD thesis abstract, 2021

It appears Clear’s main scholarly contribution to the “Frontier War” thesis will be to further normalise its militarisation by the use of words such as shown in bold above, and to introduce new conflict terminology such as the ‘Anglo-Wiradjuri conflict’ (a phrase which I predict will overtime be morphed into the ‘Anglo-Wiradjuri War’) and even new conflicts such as the ‘Narrandera War.’ These words and terminology, high-lighted in bold above, suggest that this third-generation, “Frontier War” scholar has been trained in the Marxist-inspired, critical theory, the consequences of which will be discussed below.

3. Critics of the so-called “Frontier War” Thesis

3.1 Historian, Commentator & Quadrant Editor, Keith Windschuttle

The late Keith Windschuttle [1942-2025] was almost alone as being recognised the sole public critic of Henry Reynolds “Frontier War” scholarship.

His seminal book, the Fabrication Of Aboriginal History became the go-to textbook for a countering critique of the '“Frontier War” thesis.

Figure 18 - Source: The Australian 11 Apr 2025

2002

Windschuttle’s countering arguments were articulated when he and Reynolds engaged in a robust public debate at the National Press Club (See video below, ca2003?) and on the ABC Lateline program (see video excerpt below, ca2003?)

Windschuttle detailed his critique of the “Frontier War” thesis, and its claimed massacres, in his essay series in Quadrant (2000), which he summarised as:

"The first part of [my] essay will demonstrate just how flimsy is the case that the massacre of Aborigines was a defining feature of the European settlement of Australia. The second part will examine the estimates by historians [such as Henry Reynolds and Lyndall Ryan] of the total number of Aborigines killed and show that some of the key assumptions upon which these calculations have been made are either unfounded or invented. The third part will discuss the motives behind the long tradition in Australia — a tradition begun by missionaries in the early nineteenth century and perpetuated by academics in the late twentieth — of the invention of massacre stories.

- Keith Windschuttle (Reference 3)

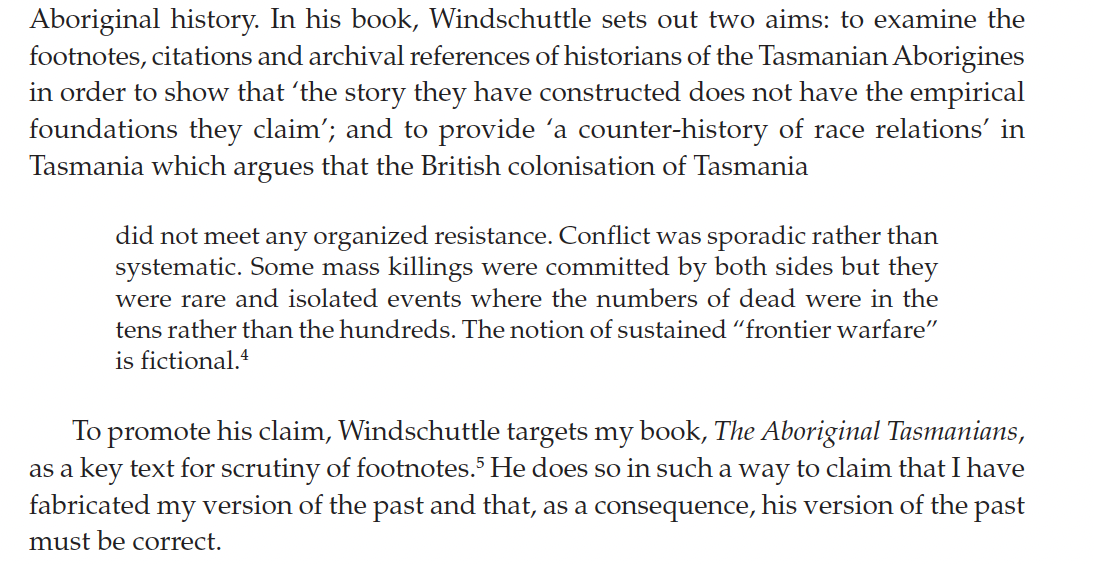

To counter Windschuttle’s points, historian Lyndall Ryan layed out, in a 2004 essay, what she saw as his critique of her work (Figure 18B):

Figure 18B - Excerpt from Lyndall Ryan, The Right Book for the Right Time?, Labour History , p May 2003, 202. Full source here as pdf

Another commentator, writing in the Australian of 22 July 2004 at the height of the ‘history wars’, described Windschuttle’s effect on the orthodox academy (Figure 18C and download).

Windschuttle’s designation as a ‘denier’ made him the whipping-boy of the “Frontier War” theorists during the History Wars of the early 2000s.

This, ‘anti-all-things-Windschuttle’, attitude was predominately driven by the advocacy and organisational efforts of Robert Manne, a former Quadrant editor himself. Manne edited, Whitewash: on Keith Windschuttle's Fabrication of Aboriginal history, 2003 and this book has been made available free on-line. This free-access status suggested that Manne and the other contributors considered it very important to make the book available as widely as possible in their efforts to overcome Windschuttle’s claims.

3.2 The Quadrant Crowd

Nothing. Six months passed without a fight. Then a year. The Quadrant crowd was silent. I’d written a book about slaughter on the Queensland frontier on a mighty scale, and the old history warriors were not out denouncing my work as lies, all lies. I thought for a time the history wars were done and dusted.

I was fooling myself.

- David Marr, The annuls of history, The Monthly, 25 March 2025 (full pdf here)

So described ABC presenter, writer and commentator David Marr, those who routinely criticise the prominence given to the “Frontier War” thesis and/or the accuracy of the historiography used to support the claim of widespread massacres of Aboriginal people.

Three of the members of the ‘Quadrant crowd’ are historian Michael Connor, Marie Hansen Fels [research historian] & David Clark [former Manager of Heritage Operations, Aboriginal Affairs Victoria].

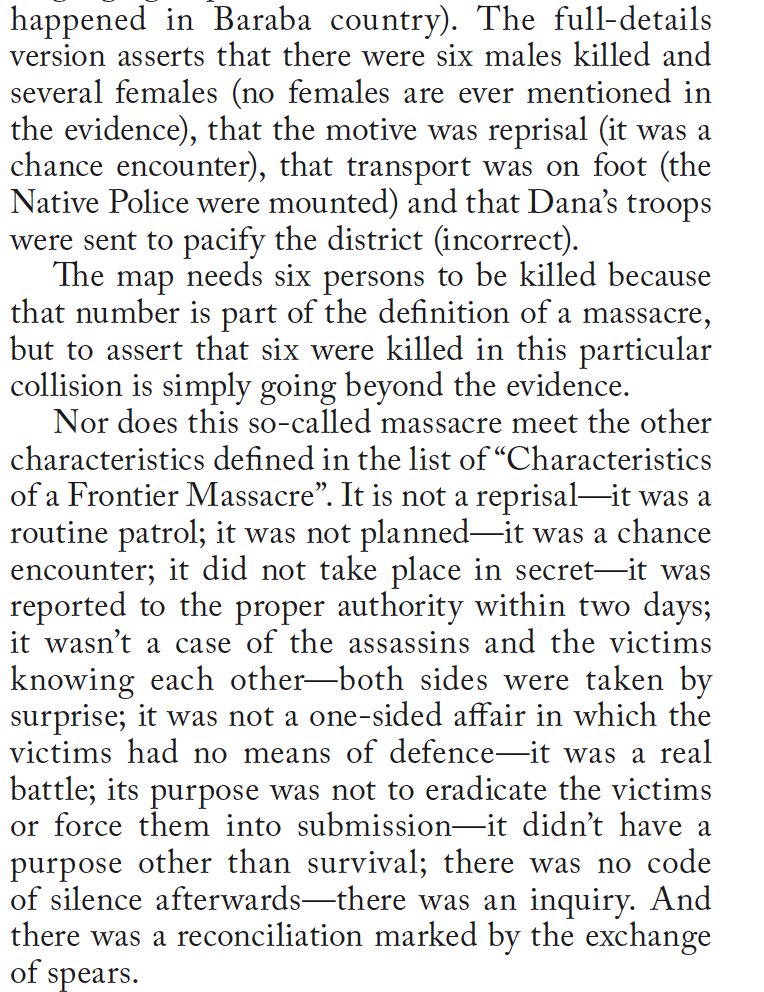

They have studied in detail one so-called massacre, the Loddon Junction ‘massacre’ and concluded that it did not happen. And more worryingly, the Aboriginal people on the ground at the time (1846) were recorded at the time as saying it did not happen:

Figures 19A - Excerpt from Fels, M. H. & Clark D., The Loddon Junction Massacre That Never Happened, Quadrant, April 2021, p67ff. (Source: full pdf here)

Fels and Clark explain why the `full-details version of the clash at Loddon Junction, on the University of Newcastle Massacre Map, was wrong to be considered a “massacre” with the death of six or more people’:

Figure 19B - Excerpt from ibid.

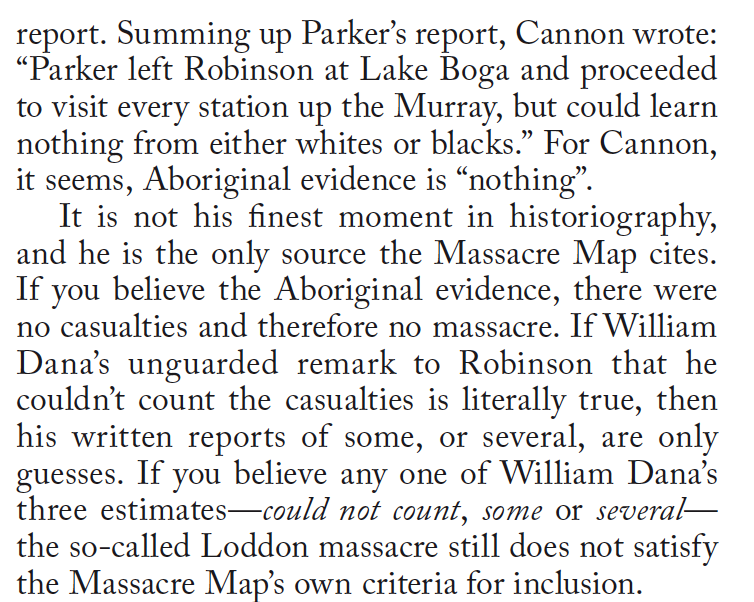

But perhaps the most worrying aspect of the historiography of the “Frontier War” thesis is just how scholars can ignore the voices of Aboriginal people - not Aboriginal people today who claim to be the bearers of accurate oral history about events from two hundred years ago - but those contemporary Aboriginal informants who witnessed the details of the conflicts first-hand, or relayed information from trusted sources.

Modern scholars have written that testimony of the contemporary Aborigines amounted to “nothing”:

Figure 19C - Excerpt from ibid.

Figure 19D - Excerpt from ibid.

The comments by Fels & Clark’s, that the voices of the Aborigines were dismissed as “nothing”, raises a disturbing question about an historian like Henry Reynolds calling his seminal book, The Other Side of the Frontier - just how much evidence for the “Frontier War” thesis actually came from the other side, the Aboriginal combatants and survivors themselves?

When a reviewer of Reynolds’ book confidently claimed his work represented the ‘perspectives of indigenous people’, just how true was this?:

“With The Other Side of the Frontier, Henry Reynolds has exceeded his intention of turning Australian history “inside out.” Through fragments and excerpts pieced together from a range of archival information - diaries, journals, newspapers, official documents - and oral narratives, he has presented the last two hundred years of the history of this continent from the perspectives of indigenous people. (Source: Louise Gray review)

Did the reviewer actually believe that Reynolds had written accounts by the Aborigines themselves, what they recorded as being their ‘perspectives’, or was she just making a politically correct claim so as to assist the advance the “Frontier War” thesis a bit further through the academy and on into the general, reading public?

Honour and Understanding Is Restored So Let’s Make-up and Be Friends

Fels & Clark, also describe an aspect of frontier conflicts that the “Frontier War” theorists seemed to have totally missed or ignored - the fact that there are many examples of both the settlers & Native Police on the one side, “making up” so that there were “no hard feelings”, with the Aborigines on the other side:

Figure 19E - Excerpt from ibid.

If there had been a concerted “War” or “Uprising” over many years, why are examples of such local reconciliation relatively common? An alternative reading of the archival literature produces many examples of local ‘making-up’ and exchanging gifts, or the gaining of employment, food or welfare, after individual disagreements, clashes or conflicts. There appears to be no evidence of a European and multi-tribe treaty process that one might expect after the end of hostilities in a “war” scenario.

This is an issue that the “Frontier War” theorists need to address.

3.3 Other Writers Offering Critiques of Violence As Being the Main Response of Aborigines to British Settlement

To my mind, the “Frontier War” theorists have selectively promoted the idea that the Aborigines predominately used violence in their response to British colonisation. This fits more neatly within a Marxist political agenda that identifies with an ‘oppressed people’ who are forcibly ‘dispossessed’ of their land by the exploitative imperialism that was the British Empire.

Within the Marxist framework, there is no allowance for the Aborigines to express their own agency, either individually or as clans, to choose, for example, to ‘come-in’ willingly and assimilate into the new Australian culture, or to craftily adopt a symbiotic intelligent parasitism with the missions, settlers and pastoralists in which food, shelter, tobacco, etc., could be obtained in exchange for the bare minimum of work.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that some Aborigines adopted non-violent sorcery against the whites as their way of fighting back against the incursions by the British.

The “Frontier War” theorists seemed to have totally ignored these supernatural Aboriginal responses. There is a need for example, to address the findings of writers such as Beverly Nance (1981) [Reference 5 at end of post and see Section 4.12 & 4.15 below] and others who suggest that a very large part of the violence and killings on the frontier was due to black-on-black aggression. It is well known that the fingers ‘pulling the triggers’ in most of the cases of Queensland Native Police actions were black fingers.

Nance also considers sorcery as a potential, an ultimately misplaced and ineffectual Aboriginal response to the British arrival (See Section 4.15 below).

4 - Fundamental Questions That Need to Be Answered by the “Frontier War Theorists”

The following, in no particular order of importance, are some of what I believe are valid criticisms of Reynolds’ “Frontier War” thesis that need to be addressed before the critics are convinced that the thesis is largely true.

4.1 - Where are the bodies?

If there was a raging “Frontier War” over large parts of Australia, for more than one hundred years as claimed by Henry Reynolds, where’s the archeological and photographic evidence?

Figure 19 - See another Dark Emu Exposed post here

Why has there been absolutely no publication of Aboriginal skeletal remains showing European-sourced, war-like trauma - broken bones lodged with lead or with cutlass marks or containing high arsenic levels (from deliberate flour poisonings) - being found in the archeological record? (Figure 20).

Why have only inter Aboriginal-caused skeletal traumas ever been documented (eg, by spear, wooden sword and club arising from inter-tribal, black-on-black conflicts)?

Why haven’t detailed reports on European-caused war trauma in Aboriginal skeletal museum collections been published? My understanding is that the Murray Black and Berry collections (more than 1600 remains of Aboriginal people) may contain examples where trauma by shooting may be evidenced, but why hasn’t this been published?

Figure 20 - Skeleton found with lodged musket ball, from an early 1800s European battle field

Figure 21A - Source background

Figure 21B - Source background

Where is the physical evidence of the killings, death and destruction of individual and groups of Aboriginal people? Why aren’t there any photographs of bodies or battle sites? (Figures 21A&B) Photography certainly was being used on the frontier from the 1880s onwards.

We know that numerous Aboriginal skeletons have been found showing trauma from inter-tribal Aboriginal killings, but none have been publicised showing cutlass or gunshot wounds, as a frequently found in other battle zones from the nineteenth century. Similarly, photographs exist showing battle scenes between the British (and the Spanish) and indigenous peoples in other colonial wars (Figures 21A&B), but not in Australia [See here for detailed discussion]

4.2 - Where is the Real Evidence Aboriginal Tribes Operated as Co-Ordinated Allies in “War”?

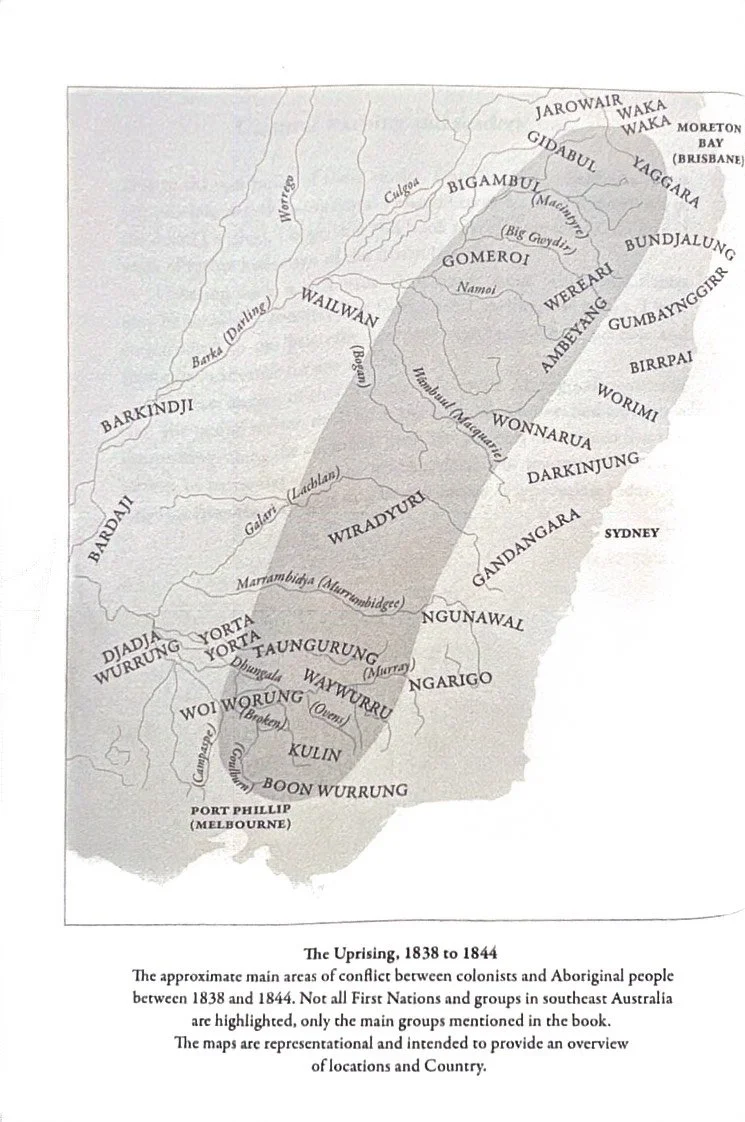

The “Frontier War” theorists need to explain how could there have been a unified ‘uprising’ , occurring simultaneously over such a huge area of NSW and Victoria, as indicated in the Stephen Gapps’ Map below, if the tribes were so disparate, spoke different, un-intelligable languages and were often bitter enemies?

Gapps in his latest book publishes a map (Figure 22) that purports to show the so-called ‘uprising’ of the Aboriginal tribes against the British settlers over a huge “front” in SE Australia. The reader is mistakenly lead to believe that this occurred as a co-ordinated event over a short six-year period.

Figure - 22 - A map of the supposedly six-year “uprising" , presented in a classical Western “war-campaign” format, that misleads the reader into thinking the Aboriginal tribes were working in a co-ordinated way from a central “war-room”. Source: Stephen Gapps, Uprising, War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838–1844, April 2025

But how could this occur given that the tribes belonged to numerous language groups that were un-intelligible to each other?

Where are the records and the evidence that the tribes were co-ordinated in a sufficient way with each other so as to effect this so-called “uprising”? Isn’t this map just a modern Eurocentric fantasy? If it was true, where are the plans, maps and records from the time used by the Aborigines and the British forces in their respective campaigns?

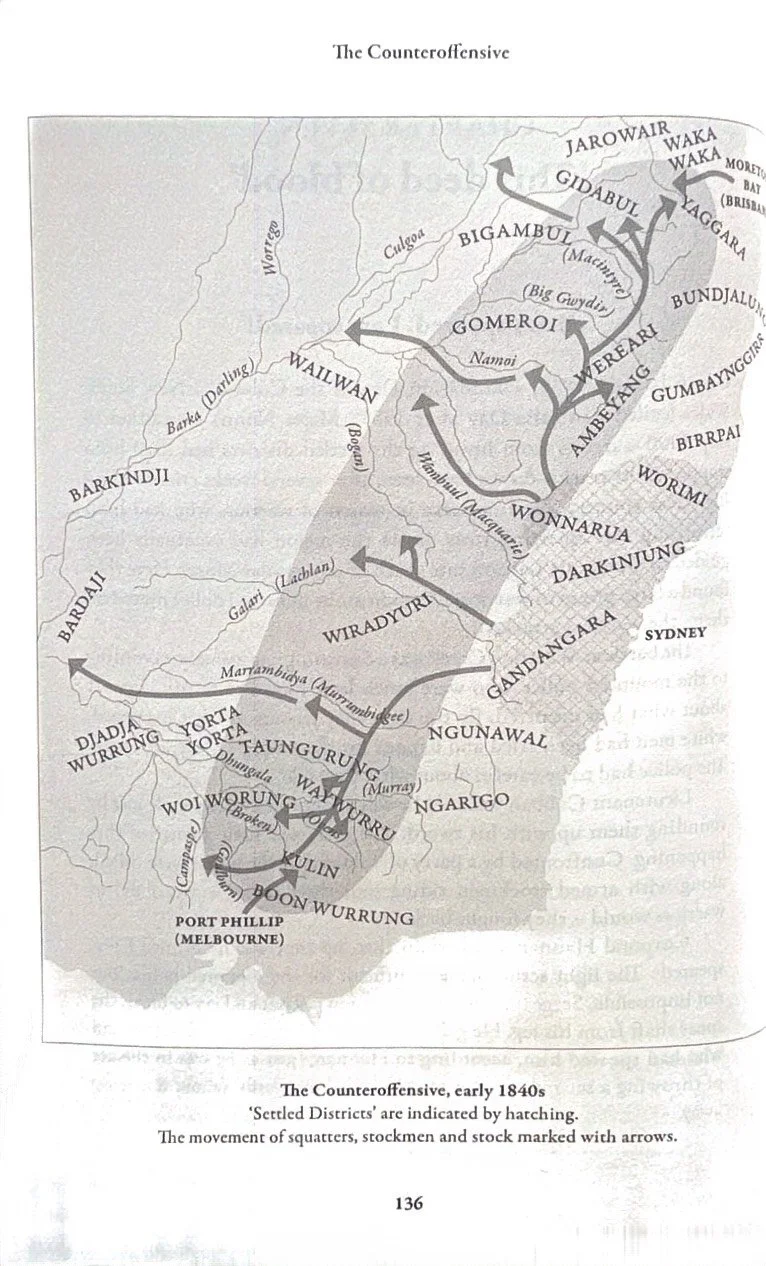

4.3 - How could it have been a “War” if the European combatants are described by Gapps as `Squatters and Stockman’? [see Figure 23]

In another map in his book, Stephen Gapps depicts what he perceives to be a ‘counter-offensive’. By using quasi-military terms such as ‘uprising’ and ‘counter-offensive’, Gapps hopes to lead the reader to accept that the events constituted a “war”.

But Gapps admits that the people involved weren’t even soldiers but simply `squatters and stockmen.’ How can civilians therefore be considered responsible for a military ‘counter-offensive’ as Gapps suggests in his map? (Figure 23)

Did these civilians have the legal basis, the weapons, time and resources, training and logistical control to undertake a ‘military counter-offensive’? Why would they even want to do it themselves rather than just complain and pressure the government to act on their behalf?

The Canberra War Memorial requires that ‘naval or military forces raised in Australia by the Crown or the Commonwealth’ as evidence that ‘Australians’ were predominately involved in this “war.” Squatters and stockman were not naval or military servicemen.

The reality is that the government did take responsibly and acted as ‘policeman’ to prevent, as best as it could under the circumstances, violence between the settlers and the Aborigines. The government did not act predominately as an ‘invading military force of conquest’ using naval or miltary servicemen.

Where conflict did occur, follow-up inquiries and reports were prepared in many cases. The surviving records of the actions are all documented - maps and all - and are all available online at the Historical Records of Australia (HRA).

As far as I can find, there was no declaration of “war” in these archives because the Aborigines were recognised as having the rights of British subjects. The conflicts and killings in the colony were treated as civil misdemeanours, thefts, native-custom murder and civilian murders.

I understand that in Australia there were only probably five occasions when these disturbances were escalated to the level ‘rebellions’ requiring martial law to be imposed to bring back order. These occurred during times of particular civil unrest - the Bathurst conflicts between the Wiradjuri and the pastoralists (squatters) and settlers, the miners at Eureka Stockade, the convicts at Vinegar Hill, the shearers in Queensland during the shearer’s strike, et al. See also here on the difficulties of the legalities of martial law and interactions with the Aborigines in colonial South Australia. None of these incidents were deemed to be a formal declaration of “war” by any of the colonial governments, or the Colonial Office in London.

Figure 23 - From Stephen Gapps’ book. If it was a “War” why are the combants described as “squatters and sockman” and not British soldiers? Was it because it the conflicts were only “civil” or under “martial law” - that is, criminal acts between British subjects and not “war” involving formal military combatants? Source: Stephen Gapps, Uprising, War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838–1844, 9781742238029 / April 2025

4.4 - How could the Aborigines consisting of hundreds of family groups, clans, tribes and language groups come together as a co-ordinated fighting force against the British?

Aboriginal peoples were not living a social structure that the British or we today would class as a nation. Merely calling Aboriginal people, ‘First Nations’ doesn’t make them so, in any practical organisational, administrative or material way. This word-play is an example of the standard Marxist belief, ‘that you could change reality by changing words’ (Reference 6 and see Section 4.13). Using the word ‘nation’ gives political credence to an Aboriginal society that actually was only ever family-, clan- or tribal-based.

In 1788, the continent of New South Wales in the east and New Holland in the west consisted of a patchwork of hundreds of tribes - each generally with their own unique language and variations of a loosely common set of belief systems, customs and culture. The “Frontier War” theorists need to offer evidence that such a diversity of independent tribes had the agency to come together to form an ‘army’, or co-ordinated guerilla force, in an ‘uprising’ to fight the British. The real evidence of Australia’s history makes this theory patently absurd.

These conflicts occurred at a time when Aboriginal people did not even know the geography of the lands beyond their immediate neighbours, let alone have a consciousness of their own tribal land or indeed the Australian continent in a ‘national’, or even a statewide, sense.

It was the British who sent Aboriginal Sydney man Bungaree with Matthew Flinders to circumnavigate the land that was to become the nation of Australia. After 50,000 years of occupation, no Aborigine had any idea of the geography of Australia, nor a conception of the country as one nation until Bungaree’s enlightenment.

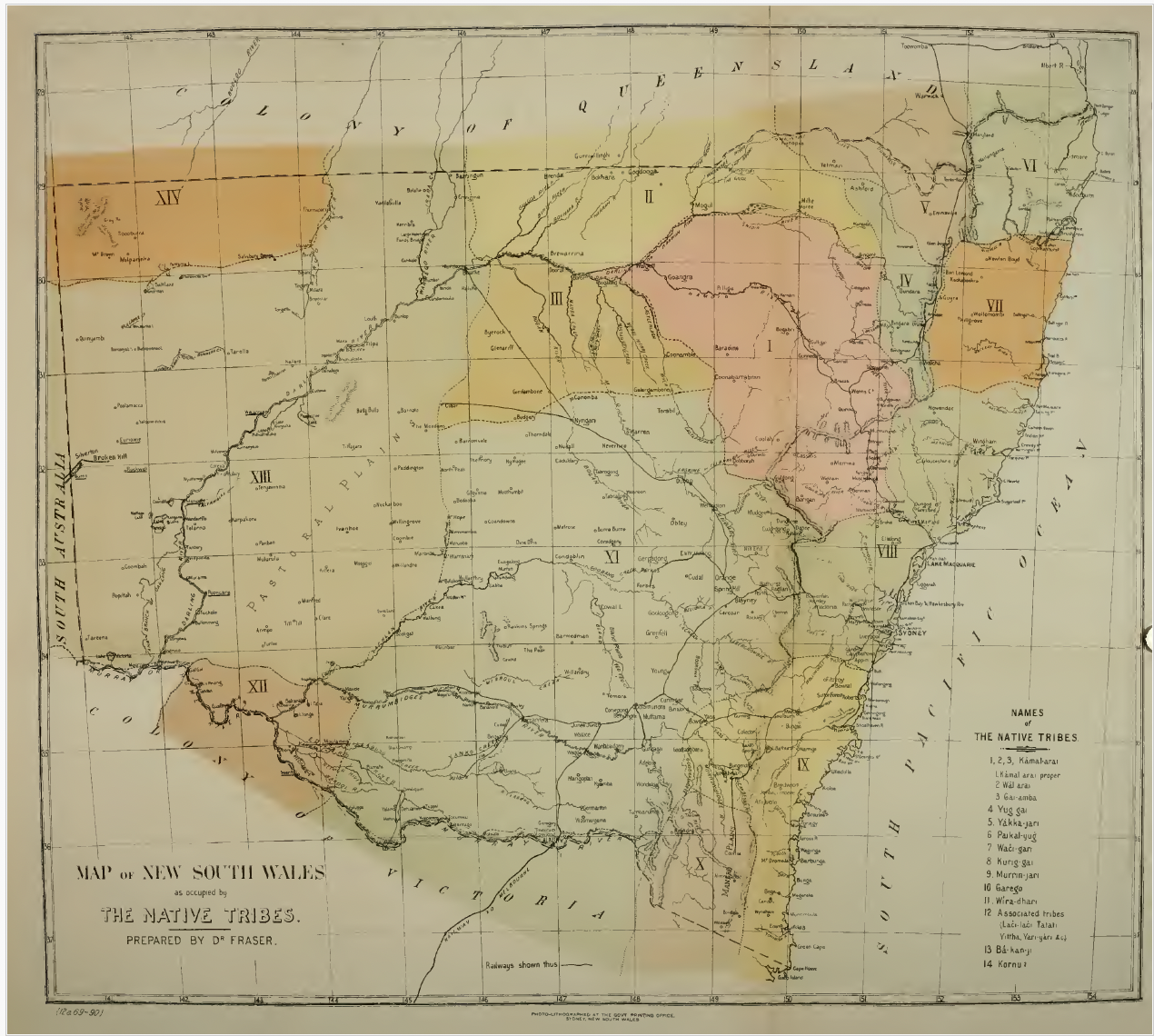

Historian Keith Windschuttle alluded to this issue in 2003 when he pointed out that there could not have been a formal “Wiradjuri War” in the 1820s given that the word ‘Wiradjuri’, in terms of being to used denote a ‘nation’, was an concocted word-invention of white men, notably by John Fraser in 1892.

Windschuttle wrote, in a letter of complaint, to the National Museum regarding one of their new exhibits that:

I would like to add now that this exhibit is also misleading in asserting that there was such a thing as a “Wiradjuri War” or “Wiradjuri country” in 1823-1825. This is because there was no group of Aborigines known as the Wiradjuri in existence in the 1820s. The term “Wiradjuri” does not derive from Aboriginal culture. It was invented by the white anthropologist John Fraser in the 1890s. I quote Norman Tindale’s The Aboriginal Tribes of Australia (1974) p 156:

By the time of John Fraser (Threlkeld, 1892: Introd.) there was such a literary need for major groupings that he set out to provide them for New South Wales, coining entirely artificial terms for his “Great Tribes”. These were not based on field research and lacked aboriginal support … During the 1890s the idea spread and soon there was a rash of such terms, especially in Victoria and New South Wales. Some of these have entered, unfortunately, into popular literature, despite their dubious origins. I list some of them for the guidance of those interested:

… Wiradjuri Nation—New South Wales…

- Excerpt from K Windschuttle submission to National Museum [but see a review of a rebuttal of Windschuttle in a book by Bain Attwood (Ed)}

Windschuttle is correct to quote Tindale (1974), who cites Fraser (1892) and his map (Figure 24). This map does indicate a big, uncoloured section XI crying out to be named, and ultimately receiving the ‘dubious’ name Wiradjuri.

Figure 24 - Fraser's Map indicate large uncoloured area of NSW that Fraser simply called all of the country of the Wiradjuri. Source: see Figure 25

Figure 25

Fraser’s book refers to Archdeacon Gunter of Mudgee as being the first chronicler in 1838 of the language of a people he called “Wirradhuri” (Figures 26 & 27). The approximate map area, based on Gunter’s description, roughly shows the extent of the country occupied by this original “Wirradhuri” tribe. (Figure 28).

It is Fraser in 1892 who greatly expands this map area to the extent of the modern “Wiradjuri nation” claims of today, unjustifiably as Windschuttle suggests.

Figure 26

Figure 27

Figure 28 - Map area of the original “Wirradhuri” tribe. Fraser in 1892 greatly expanded this map of the now “Wiradjuri”

Figure 29 - Inscription in Gunter’s Wiradjuri vocabulary book

4.5 - Even Today So-Called Wiradjuri People Are Not Unified Enough to Fight For a Common Cause

It is hard to imagine that all the disparate tribes, speaking different languages, in colonial NSW and the Port Phillip District in the 1830-40s could somehow overcome their differences and unite in an ‘uprising’ against the British.

Even today, when Aboriginal people all speak the same language - ironically English - they are constantly disagreeing on how to engage with modern Australian society. Many Wiradjuri are refusing to recognise other ‘self-identifying’ Wiradjuri (Figure 30). There is even a break-away Wiradjuri group who differentiates itself by concocting their own linguistic spelling of the tribal name with a “y” - Wiradyuri (Figure 31). [Ed. note: To an outsider, the irony is delicious - a group of modern, English speaking Aussies, ignore the traditional linguistic nomenclature used for the Aboriginal “-dj-” sound by substituting their self-inspired version of “-dy-” instead, and then, applying face-paint, holding a set of clapsticks and wrapping themselves in possum-coats, call themselves a new break-away “Wirady[j]uri” group, a la Monty Python].

Figure 30 - Source

Figure 31 - Source

Figure 32 - “The Peoples Front of Wiradyuria” ? - Is the whole thing just a joke?

The in-fighting amongst the Wiradjuri/Wiradyuri reached a climax recently with the rejection of ten year’s planning to build a gold-mine on Wiradjuri/Wiradyuri country.

To convince their critics, the “Frontier War” theorists would need to provide solid primary evidence for their claims that the ‘uprising’ was a co-ordinated multi-tribal event within the wide expanse of what today is claimed to be Wiradj[y]uri country.

4.6 - If there were Wide-scale “Uprisings” Against the British, How Come Aboriginal People were Recorded As being Against the Actions of ‘rebel’ Leaders such as Pemulwey?

As Governor King wrote in a despatch to Lord Hobart in 1802, many Aborigines had become ‘domesticated’ [assimilated] and looked upon the violent actions of Aboriginal criminals, such as Pemulwey, as being unnecessarily ‘troublesome’ and they ‘reprobated the conduct of the natives…and expressed sorrow’ that Pemulwey had such a great [bad] influence over them. (Figures 33&34)

Figure 33

Figure 34

The “Frontier War” theorists need to explain why so many Aborigines from Bennelong and Bungaree down to a myriad of those that worked peacefully on farms, in whaling and for the missionaries, as well as those that just ‘came in’ to part-settle on missions, did not take up arms against the British in Stephen Gapps’ so-called “Uprising”.

It just doesn’t make sense that there was a “War of Resistence” when so many Aboriginal people exercised their own agency and quietly assimilated into the new colonial society voluntarily. Their actions lend support to the argument of Windschuttle and others that the settlement of Australia was one of the least violent in the history of human colonisations.

4.7 - Why Was there No “War” From Day One?

When Phillip landed with the First Fleet to establish the penal settlement on Sydney Cove in 1788 there was no opposition from the local Aborigines that resembled anything like a “war”. This is the one biggest problems with the “Frontier War” thesis - if the British ‘invaded’ and set about undertaking a ‘violent conquest’ why were there no set battles or ‘war-like’ conditions between the British soldiers and the various Aboriginal tribes from Day One?

Stephen Gapps called his first book The Sydney Wars, yet if it really was a “war” then why was the death toll so low?

Gapps included, as an Appendix in his book, the numbers of settlers, convicts and soldiers, as well as the Aborigines, who were killed in the conflicts during the so-called “Sydneys Wars”.

In the period of these “wars” - the 28 years from 1788 to 1816 - Gapps himself could only find evidence that some 80 British settlers (including convicts and soldiers) and 85 Aborigines had been killed. I have taken his “Sydney Wars Casualties” listing from his Appendix (here) and summated the casualties and represented them in tabular form in Figure 35.

Figure 35 - A basic tabulation of Stephen Gapps’s so-called “Sydney War” Casualty List. Source: Gapps, S. The Sydney Wars, 2018, p274ff

Of course all these deaths are lamentable, but these figures hardly represent “war-like” casualty rates - 166 deaths on both sides over 28 years, or 6 deaths per year.

For comparison, the number of murders in modern-day NSW, in 2019 alone, was 76 (Figure 36). This is more than ten times the number per year that occurred during the settlement of Sydney.

Gapps therefore wants us to be shocked/sad/remorseful and/or feel guilt for a time when he says the colony was at “war” when in fact today we all live in the same city with about the same number of citizens being murdered each year that were killed in settlers/Aboriginal clashes over a 28 year period in colonial times 250 years ago.

Figure 36 - Numbers of murders in modern-day NSW (2019) . Source ABS

Thus, many would believe that Gapps’ own figures fail to support his claimed “Frontier War” narrative in the early years of Sydney’s settlement.

4.8 - If Gapps Claims that a Death Toll of 86 Aborigines Constitutes the Sydney Wars, what About Inter-Tribal Massacres of the Same Order?

Two massive Inter-tribal Aboriginal massacres are so well known that they have their own Wikipedia pages - The Warrowen Massacre in the early 1830s at a site in modern day Brighton in Melbourne with a death toll of some 77; and the Massacre of Running Waters in 1875 in Central Australia where about 80-100 Aboriginal men, women and children were killed by a large Aboriginal raiding party.

If Gapps thinks that a death toll of 85 Aborigines over 28 years justifies the term the Sydney Wars then, by this reasoning, can we think of the Warrowen and Running Waters events as “Aboriginal Civil Wars”? Each of these bloody events, occurring over the course of one day, killed about the same number as the British did in 28 years in early Sydney.

This notion of ‘Aboriginal Civil Wars’ would seem to open-up a whole new avenue of enquiry as discussed in the follow sections.

4.9 - Did the British actually start the “Frontier Wars”, or instead, did they blunder unwittingly into the ‘Aboriginal Civil Wars’ that were already well underway?

There is a developing thesis that there was no “Frontier War” as such between the British and Aboriginal Societies in the early settlement of Australia. Rather any frontier violence was due to the constant and continuing inter-tribal wars into which the British blundered from time to time. One could view these as ‘Aboriginal Civil Wars.’

Coupled with the settler/Aboriginal violence due to thefts, spearing of stock, killings of shepherds and misunderstandings over payment for Aboriginal women these conflicts go a long way to explaining all the violence that occurred on the colonial frontier.

Very little, if any of the frontier violence was due to a formal recognition by the Aborigines that their land was being ‘dispossessed.’ The idea of land as property, that the Aborigines could be dispossessed of, is solely a Eurocentric social construct. Land as being a separate asset did not, in fact could not, enter into the Aboriginal mindset. Aboriginal people, their spirits, plants and animals and the land - “Country” - were all parts of one indivisible cosmos. The Aborigines in each tribal area were instead focussed on how to respond to interlopers to this cosmos - whether they be the British settlers or other Aboriginal tribes - who competed for the local resources and women and threatened to upset their local, societal structures. Each Aboriginal clan had to decide whether to fight, ignore or accomodate these interlopers.

There is mounting evidence that the landscape was under frequent `Aboriginal Civil Wars’ and that the so-called British-on-Aboriginal conflicts were not “Frontier Wars” but rather just the inevitable violence that occurred when separate groups are competing for the same ‘cosmos’ of local resources.

For example, the Sydney penal settlement diarist, Watkin Tench, seems to have been an early observer of the fact that the inter-tribal Aboriginal Civil Wars took precedence over any Red-coat/Aboriginal conflicts. If the “Sydney Wars” were in full swing, as Stephen Gapps would have us believe, why was Tench, and other officers, able to observe examples of the British being were totally ignored by the Aboriginal warriors?:

From circumstances which have been observed, we have sometimes been inclined to believe these people at war with each other. They have more than once been seen assembled, as if bent on an expedition. An officer one day met fourteen of them marching along in a regular Indian file through the woods, each man armed with a spear in his right hand, and a large stone in his left: at their head appeared a chief, who was distinguished by being painted. Though in the proportion of five to one of our people they passed peaceably on.

- Transcript from Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany-Bay, May 8, 2006 [eBook #3535] (see Figure 37)

Figures 37A - Extract of [civil] “war” references.Source : Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay 1789, p87-8, Original image at GoogleBooks Online

Figures 37B

If the “Frontier War” thesis was true, why then did these Aboriginal warriors just ‘pass peaceably on’, straight past the British redcoats, Gapps’ ‘enemy soldiers’?

Figure 38 - The Aborigines, on their way to a ‘civil war’, just pass on by the British soldiers. Source: AI construct

Similarly the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, reported on 29 Dec 1805, (p. 2) that:

“A desperate conflict took place among natives on Thursday near the Military Barracks; and a number of spears flying, a private of the New South Wales Corps received one by accident in the foot, which penetrated to some depth. The combattants were a long time prevented by the curiosity of crowds of spectators, who pressed upon all sides, from the continuance of hostility; but several Officers and Gentlemen interfering in commanding that no interruption should be offered to their customs, the battle shortly after closed and in a few seconds the field groaned beneath the weight of numbers falling under the waddy whose aperient powers furnished in a twinkling an unpleasant spectacle of fractured heads and half expiring veterans.

Their mode of assault and defence with the waddy is certainly entitled to remark; for notwithstanding the most violent rage and impetuosity, yet the head is the only part guarded; every other being here opens to the blow of the antagonist, who never avails himself of the advantage but hammers at the head of him who endeavours to confer a lasting obligation on his own. The conflict which was truly spirited while it lasted, was provoked by the conduct of Wilbamanan, no less remarkable to his countrymen for his manly courage and prowess than for his perfidious manners; who attempted to force away the wife of a native from Broken Bay; in which attempt he eventually succeeded, after the unhappy object of contention had undergone the terrible fatigues and barbarities consequent on a savage rivalship that holds in contempt the female choice and inclination.”

If the British settlers were at “war”, why was only a ‘spectator’, one soldier of the NSW Corp, injured by accident? Why did the Aborigines only fight each other, while the so-called British ‘enemy’ just press around as spectators? Why did the Aborigines just seem to carry on their normal social life despite having the British penal colony ‘dropped’ in amongst them?

Similar pieces of evidence for the ‘‘Aboriginal Civil Wars’ thesis, including genocide (‘whole tribes have been exterminated’), were reported from the Port Phillip District, as recalled by Edward Parker during a lecture in Melbourne in 1854 (Figures 39-41):

Figure 39 - Sources - ADB and. Source-wikipedia

Figure 40 - Source Trove for download

Figure 41A - Extract from E S Parker’s 1854 Lecture. Source: Trove - Page 16 (image 18)

Figure 41B - Extract from E S Parker’s 1854 Lecture. Source: Trove - Page 20 (image 22)

The idea that the presence of the British actually decreased or even eliminated inter-tribal ‘civil war’ is supported by Parker’s observations that, ‘as one man [native] said to me’:

Before you came here, the country was strewed with bones and we were always at war; but now you say , Do not fight, do not kill; it is a strange speech. (Figure 41A).

4.10 - There are Frequent Records of Severe ‘Civil Wars’ Between Aboriginal Tribes at the Time of Colonisation

During the settlement of the Port Phillip District, as the frontier spread out across what was to become the State of Victoria, many early records attest to the violent, inter-tribal conflicts that were endemic in the Victorian Aboriginal societies.

There is a developing thesis that there was in effect an indigenous 'civil war’ underway in pre-colonial Victoria when the British settlers first arrived.

Historian Ruth Gooch’s scholarly work on the influence of the Aboriginal guides in the colonisation and settlement of Victoria offers a countering insight to the ‘all-encompassing view of violent dispossession.’ Her work suggests that describing colonisation only in this way is ‘clearly flawed, when the [Aboriginal] guides are an essential part of the land alienation story.’ That is, not all Aboriginal people put up a ‘resistance and guerilla campaign’ or fought “Frontier Wars” - many in fact acted as guides to show the settlers where the best pastural country was.

Gooch cites many sources which indicate the severity of inter-tribal conflict that was underway at the time of first-contact. This suggests that ‘civil wars’ were a normal state of affairs in pre-colonial Aboriginal society in the Port Phillip District. (see some of the citations of Gooch’s paper in Figures 42B & C).

Figures 42A - Source: Ruth Gooch (2018) Why did Aboriginal guides co-operate? Settlers and guides in Victoria 1835–1845, History Australia, 15:4, 785-803,

Figure 42B - Records of inter-tribal ‘civil wars’

Figure 42C - Records of inter-tribal ‘civil wars’

4.11 - These Aboriginal Civil Wars Led to Tribal Boundary Changes

The “Frontier War” theorists will need to explain why the British/Aboriginal violence on the frontier was any different from the Inter-tribal violence of ‘civil wars’ that wracked Aboriginal societies in pre-colonial times. The concept and violence of ‘tribal land dispossession’ did not arrive with the British - it was already the norm in pre-colonial Aboriginal societies.

For example, academic Elizabeth Ellender has studied the changes in tribal boundaries of some South Gippsland tribes that were caused by what a developing thesis would call ‘Aboriginal civil wars.’ These were “wars” that were well documented and resulted in several ‘genocidal’ conflicts between the tribes (Reference 4, Figures 43A&B).

Figure 43A - “Original” boundary ca 1830s between the clans of the Bunurong [left of black line] and the Gunai/Kurnai [right side]. Source: Reference 4 - Elizabeth Ellender (2002) p10

Figure 43B - “More recent ” boundary ca 1840s between the clans of the Bunurong [left of black line] and the Gunai/Kurnai [right side] after several “genocidal battles & wars” that lost a big slice of the Bunurong to teh Gunai/Kurnai. Source: Reference 4 - Elizabeth Ellender (2002) p10

4.12 - Were Tribal Associations Just Opportunistic Short-term Alliances to Win Resources rather than a Concerted Militaristic Strategy Against the British?

“Frontier War” historians and commentators are developing a thesis that Aboriginal tribes consciously acted as ‘associations’ in a concerted effort to push back at the so-called ‘dispossession’ of their land by the British.

But for this Pan-Aboriginality consciousness to be true, the theorists need to explain why the hatred of one Aboriginal tribe by another was as high, if not higher, than any hatred the Aborigines may have had towards the British and settlers. Why is there so much evidence that blacks hated other blacks more than they hated whites? This is hardly an observation one would expect from associations of First Nations Peoples putting up a spirited, frontier-wide, guerilla “war” against the invading British forces.

For example, Beverley Nance in her 1981 study of violence in the Port Phillip District (colony of Victoria) concluded that the records indicated that, at a minimum, some 400 Aborigines were killed by whites between 1835 and 1850 in Victoria. In ‘contrast, only 59 whites were killed by Aborigines over the same period’ and more surprisingly, ‘the number of Aborigines killed by other Aborigines, possibly 200 or more, far outweighs the violence of Aborigines against whites’. (Figures 44A&B)

Figure 44A - Page 533 Extract from, Nance B., (1981) - The level of violence: Europeans and aborigines in Port Phillip, 1835–1850, Australian Historical Studies, 19:77, 532-552

Figure 44B - Page 533 Extract from, Nance B., (1981) - The level of violence: Europeans and aborigines in Port Phillip, 1835–1850, Australian Historical Studies, 19:77, 532-552

Thus, Nance raises some important points that the “Frontier War” theorists need to address - if it was a formal black-on-white war, why are the death tolls from black-on-black violence so high? Did the settlers stumble upon an ‘Aboriginal Civil War’ in progress?

And why were there so few incidences of blacks killing whites - only 59 as Nance found? If it really was a “Frontier War” in Victoria, why didn’t the Aborigines show more mettle and undertake more ruthless attacks on the settlers? As far as I’m aware, there were very few black-on-white massacres in Victoria [eg Faithfull massacre being the exception rather than the the rule].

Some of us are now asking - should we look upon this whole period of settlement of Victoria, not as a British ‘war of invasion’ but rather, as one in which the settlers merely arrived and easily acquired a country so wracked and weakened by Aboriginal civil wars and internal conflict that the Aborigines had no hope of defending their country in a concerted way?

To be trueful, Nance’s minimum death toll of 400 Aborigines, out of a population of some 10,000, is still a significant statistic - it represents about 4% of the Victorian Aboriginal population at the time of first contact. As Nance points out, it is ‘a great loss’.

By comparison Australia’s ‘great' losses in the First World War were about 1.1% of Australia’s population at the time (Figure 45).

Figure 45 - Australian Casualties in WWI. Source Australian War Memorial

But then, four hundred deaths is still ‘only’ about the number of people killed on Victorian roads every two years. Very sad, and highly regrettable, but a price that is not so high that we would wish vehicles had ever been allowed to ‘conquer’ our roads.

Similarly, for the 400 Aboriginal people killed over the 15 year period 1835-50 [equivalent to 2,565 Vic road deaths based on 15yrs x 171(the annual avg death toll)] - it is very sad and highly regrettable, but a price our society paid for the benefits of colonisation and the creation of the great State of Victoria.

Even writers who were very sympathetic to the plight of the Aborigines, noted the Aborigines desire to ‘annihilate’ their neighbouring enemy tribes at every opportunity. George Henry Haydon [1822–1891] for example, published in 1846 his experiences of Five years experience in Australia Felix [Port Phillip District]. Haydon clearly recalled the Aborigines taking whatever opportunities, including those offered by British colonisation, to seek revenge against their black enemies (further evidence of an Aboriginal Civil War?) (see Figures 46A&B)

Figure 46A - Haydon, G.H. 1846. Five years experience in Australia Felix, London, p151

Figure 46B - Haydon, G.H. 1846. Five years experience in Australia Felix, London, p152

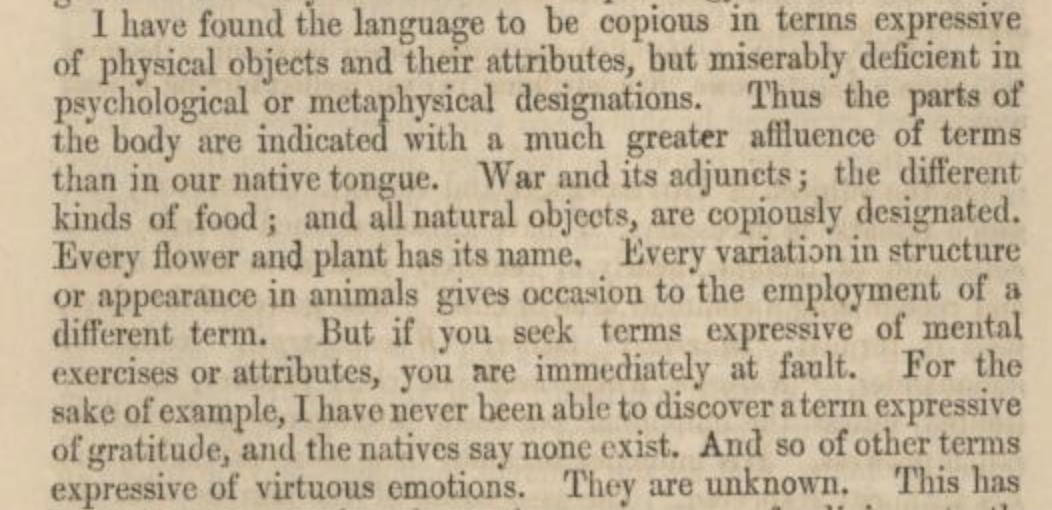

Evidence of ‘Aboriginal Civil Wars’ in Tasmania?

There is archival evidence that Tasmanian Aboriginal societies were not infrequently in a state of violent tribal flux - what some today might view as evidence for ‘civil wars’ within the hunter-gatherer bands fighting principally over access to women:

Figure - Windschuttle, Keith, "Mabo and the Fabrication of Aboriginal History" [2003] Samuel Griffiths Association Conference 14; (2003) 15 Upholding the Australian Constitution Ch 11.

4.13 - Why Do the “Frontier War” theorists Only Focus on Violence and War as the Sole Aboriginal Response to the British Settlement of Australia?

Is there an Underlying Marxist Agenda?

One reason why many Australians are loath to accept the “Frontier War” theory at face value is because the theorists always turn up at their lectures with a ‘red flag’, literally.

There are many Australians of good faith who are willing to engage in debate about Aboriginal and settler violence on the frontier during the settlement of Australia. But our experience is that inevitably the debate is quickly politicised along Marxist lines in an effort to deligitimise Australia and the Australians.

Communists cannot accept, indeed they are embarrased by, the successful, free-enterprise, liberal democratic, nation state of Australia that was created by real working classes of British and foreign convicts, settlers, migrants and refugees, independent of any Marxist input.

Communists and radical socialists therefore look to co-opting the “Frontier War” theory by claiming that the settlement of Australia was based on the “original sin of Australian colonisation” [Henry Reynolds’ declares this view here ]; or is based on the creation of a ‘fake history’ of “Cook, Convicts, Sheep, Gold, Eureka Stockade, Galipoli” as claimed by ABC presenter & author David Marr here from 02:04 [really? how can Marr call this history “fake” - that it didn’t happen - and keep a straight face?]; or is responsible for “stealing the sovereignty of the First Peoples” which they never ceded [Aboriginal tribes had no sovereignty in 1770-1788, so they actually had nothing to cede or have stolen in the first place].

The ubiquitousness of this Marxist framing amongst the ‘political Left’ in Australia is perfectly illustrated by the opening comments of former Labor Premier of Victoria Steve Bracks in a recent Yoorrook Commission report (Figures 47A&B):

Figures 47A & B - Extract of Foreword from the Yoorrook Truth Be Told report, 1 July 2025. Source

Figure 47B

What the Labor governments of Victoria are doing is merely what their Marxist ideological training has always conditioned them to do - viewing everything in their society through the lens of class and/or race, and dividing people into the oppressors and the oppressed.

Figure 48 - Excerpt of a typical modern Marxist Manifesto of ideology with regard to so-called Indigenous “genocide”, “sovereignty”, etc. Source

A real understanding of what is going on with the “Frontier War” thesis is not to be gained by looking at this solely as a phase of Australian history that was a lamentable, with its regrettable loss of life and the destruction of traditional Aboriginal societies, that it clearly was.

Instead, the real reason why this theory was (re)-invented in the 1970s, some 150 years after the events it depicts, is because of its value in progressing the Marxist cause for the ‘break-up’ of Australia’s current political and economic system. The notion of an oppressed class of the ‘Aboriginal race’ - whether it be true or imagined, that is not the point - is a very useful when weaponised by politicians in Victoria today who seek to impose their Marxist [or at least Socialist] agenda.

There has been a long slow ‘march through our institutions’ by the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) with regards to the use of the Aborigines to achieve their Marxist goals.

The CPA manifesto that was published in 1931 has been such a guiding blueprint that even former Premier Steve Bracks’ Yoorrook Commision comments in 2025 (Figure 47) are completely aligned with the sentiments of the CPA of 1931 (Figures 49).

Figures 49A - Heading f the seminal Communist Party of Australia Manifesto on the Aborigines. Source: Full pdf here

Figure 49B - The opening paragraph of the 1931 CPA Manifesto on the Aborigines which expresses a sentiment that is exactly the same as being expressed today within Labor’s Yoorrook Commission.

Figure 49C - The closing paragraph of the 1931 CPA Manifesto on the Aborigines which expresses a sentiment that underlies the ideology on display at the Dhuluny Conference 15-6 August 2024 below in Section 4.12

One should always be aware of the old Marxist belief, ‘that you could change reality by changing words’. (Reference 6).

This is why the “Frontier War” theorists are so creative with our the language in trying to change the perception of how Australians will come to view colonial Aboriginal-settler relations - if they constantly use and redefine words such as ‘First Nations’, sovereignty, war, uprising, guerilla tactics, campaign, slavery, et al., ultimately they will succeed. Young Australians will just take it for granted that Australia was settled violently and unjustly, with much blood spilt. A new orthodoxy of the illegitimate settler colonial state based on an original sin will have been established, even though this narrative is patently untrue.

4.14 - Is the “Frontier War” Thesis Just a “Front” for the Political Agenda of the Radical Greens and Marxists?

Unfortunately, there is a specific thought process that one needs to go through before opening any conversation within the ‘cultural or history war’ spaces in Australia today.

Before engaging one should always carefully look at one’s debating opponent and ask oneself, “Is this a well-meaning person who might criticise me or my position, but they do it because they want me and my society to be better - are they are bringing honest, constructive criticism to the conversation in good faith?”

Or, do I need to carefully study my opponent and look for the political baggage and ‘red-flags’ that they may be carrying that indicates that they just hate me and my views, and the politics that I represent. Their critique of my position will not be about searching for the truth in our country’s historical events, but rather will be focused on attacking me personally and pulling down my arguments whether they have merit or not. They are bad faith actors in that they will use misinformation, disinformation, and outright fabrication and lying if need be, to win the battles of political argument and the ultimate the war in progressing their agenda for a New Society in Australia.

Many of us today have a great suspicion that the recently invented (or re-invented from the 1930s CPA) “Frontier War” theory is just another Marxist meme that is being used to delegitimise Australia.

Those proponents of good faith, who honestly believe that the Australian frontier was settled a lot more violently than many historians of the past (and Windschuttle’s allies today) have admitted, will need to have an explaination as to why they are keeping company with those who are openly Marxist or Communist.

For example, at the two-day Dhuluny Conference 1824-2024: 200 Years of Wiradyuri Resistance that was held at Charles Sturt University Bathurst on 15-16 August 2024, many might have been a little surprised at the list of attendees.

The conference was ostensibly called to commemorate the 14 August 1824 declaration of martial law in the Bathurst region. This was said to be the first use in New South Wales of martial law against Aboriginal people. This bicentenary was advertised as:

an opportunity to focus on the legacies of these events and their consequences for Wiradyuri people, settlers and colonists of the Bathurst region. It is also a time to progress reconciliation by marking these shared histories and how they are reflected in the broader history of the Australian (Frontier) Wars.

So far, so good, many history enthusiasts might have thought. But then they began to notice the ‘red-flags.’

4.14.1 - Lynda-June Coe

Why for example, was one of the keynote speakers at a history conference, Lynda-June Coe, a political activist and Greens Party candidate? (Figures 50-2)

Figure 50 - Source

Given that many suspect that the real agenda behind the “Frontier War” thesis is political, and not based on any genuine desire to discover and understand our colonial history, the selection of this key-note speaker is not surprising.

Neither is it surprising that Coe is happy to appear on the same political platform as Senator Lydia Thorpe (Figure 52). Senator Thorpe is well known as a promotor of the “Frontier War” theory as well as a denier (or at least is completely closed-lipped) of the black-on-black massacres carried out by her own tribal ancestors. She has not publicly acknowledged the Worrowen Massacre carried out by ‘her people’ in the 1830s - some 77 men, women and children of the Bunurong tribe slaughterd by Senator Thorpe’s Kurnai/Gunai ancestors.

This denial is a clear ‘red-flag’ that ‘massacres’ are being used solely as a political weapon and that the Greens have no real desire to be open-minded about our history, warts and all.

4.14.2 - Professor Marcia Langton AO

Also at conference giving a keynote lecture was Professor Marcia Langton AO, whose political history associated with Marxist causes speaks for itself, even if she does deny it at every opportunity.

Figure 53 - Dhuluny Conference keynote speaker, Professor Marcia Langton AO

Despite many of Professor Langton’s political, ethical and moral views being an anathema to my own, one must admire her for doggedly pursuing her philosophy that, “the world is run by those who show up.”

So here she is again, tirelessly working for ‘the cause’, and ‘showing up’ at an obscure conference to lend what support she can to the Marxist-inspired, “Frontier War” thesis.

4.14.3 - Teela Reid

Also contributing to the conference will be lawyer Teela Reid who gained some notoriety during the 2023 Voice referendum campaign for her Marxist views, views.

Figure 54 - Lawyer and activist and communism advocate, Teela Reid, speaks at the two-day Dhuluny Conference 1824-2024: 200 Years of Wiradyuri Resistance that was held at Charles Sturt University Bathurst on 15-16 August 2024.

4.14.4 - Why is an Historian from the War Memorial Attending the Dhuluny “Wiradjuri War” Conference?

Figure 55A - Australian War Memorial Historian, Rachel Caines attended the “Wiradjuri War” Conference, whose attendance was presumably sponsored by the War Memorial itself.

Figure 55B - Excerpt from Conference Notes. Source

It is a speculative question on my part, but did the Australian War Memorial sponsor one of their historians to attend this conference as a way of gathering more support and evidence to justify any decisions to commemorate the “Frontier Wars” at the Memorial?

4.14 - The Deeply Racist and Divisive Undertones of the Dhuluny Conference

To an outside observer there is something deeply divisive, indeed racist, about some of the terminolgy used at the Dhuluny conference. For those of us who grew up in the anti-Apartheid era of the 1970s-80s, there is an uneasy feeling that Australia is heading on the same path that South Africa did.

For example, the attendees who claim to be Aboriginal specifically referred to their ‘race’ as a way of distinguishing themselves and creating a sense of ‘separateness’ (aparthied) from ‘the other’:

Wirribee Aunty Leanna Carr-Smith; Yanhadarrambal Uncle Jade Flynn, Lynda-June Coe is a proud Wiradjuri and Torres Strait Islander woman, Mina Murray is a Wiradyuri woman, Associate Professor Jeanine Leane is a First Nations Writer; Karlie Alinta Noon is an accomplished scholar descendant from the Kamilaroi and Wiradjuri peoples in east Australia, Lachlan McDaniel belongs to the Kilari Clan of the Wiradjuri Nation. Rebecca, is a proud Gomeroi Woman from Moree NSW. She also has ancestral connections to Dunghutti (Walcha NSW) and Ngoorabul (Glen Innes NSW).

In contrast, some of the non-Aboriginal attendees are clearly identified as such with the additional implication that they are ‘settlers’ occupying unceded Aboriginal land, for example: Dr Clear is a non-Indigenous historian living in Sydney, on the lands of the Wallumedegal clan of the Dharug nation.

4.15 - What If Sorcery and Not Violence was the Primary Aboriginal Response the British Settlement?

It comes as no surprise to some critics of the “Frontier War” thesis that the Marxists, Greens and other activists in the above section concentrate on the use of violence as the main way that the dominate class - the British settler - interacted with, and oppressed, the minority Aborigines - the victim class.

For if the use of violence is the modus operandi of these interactions, then that gives the go-ahead for the activists to use the standard Marxist response of using violence - political, economic and military - in return. By framing the settlement of Australia as just a series of “Frontier Wars” in which the Aborigines fought back militarily under legitimate rules of engagement, the activists of today can then be justified to use terms such as “war, uprising, resurrection, genocide, unceded land, sovereignty, treaty, reparations, recognition at the War Memorial, etc.”

But what if violence was not the main response? Historian Beverly Nance observed that the Aborigines themselves did not always blame the white man directly for Aboriginal shootings and deaths on the frontier:

Figure 55 - Beverly Nance (Ref 5), p548