Mr Pascoe's Imaginary Aboriginal Irrigation Schemes

Mr Pascoe devotes six pages in Dark Emu (Reprint 2018, p45 – 50) under the subheading of ‘Irrigation’, where he provides examples of Aboriginal ‘dams’, ‘irrigation trenches’, ‘wells’, ‘stream diversions’ and ‘channels’. Mr Pascoe claims that this,

“…evidence insists that Aboriginal people right across the continent were…irrigating…” and “…did irrigate [and] alter the course of rivers…” - Dark Emu, reprint 2018, dust jacket blurb.

Our analysis of Mr Pascoe’s ‘evidence’ however leads us to believe that Mr Pascoe is greatly exaggerating the size, scope and occurrence of Aboriginal dams in pre-colonial Australia.

In the following examples we have compared the ‘evidence’, as presented by Mr Pascoe from his sources, with what these original sources actually have to say.

Example 1 - Explorer Ernest Giles’ dams

Mr Pascoe writes ;

“In 1875, Giles found a dam near Ooldea, South Australia (on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain); it had a bank of 1.5m meters high, and was 1.5 meters at the base. An overflow channel to allow floodwater to spill away without damaging the wall had been built on one side. Giles thought of the works as crude, but ‘for a full week it watered seven men, 22 camels and filled up enough water containers to last them on a dry stage of 500 kilometres’ – Dark Emu, Reprint 2018, p 47, quoting reference # 57.

Our checking of the source for this ‘evidence’ cited by Mr Pascoe, finds that, surprisingly, he did not consult the explorer Giles’ actual journal for this ‘evidence’, but rather he quotes from an article by the farmer and writer Eric Rolls in the Tasmanian quarterly, literary magazine, Island, which is described in Wikipedia as a, “forum for Tasmanian writers and writers from around Australia and elsewhere to publish new work.” Unfortunately this magazine issue is out of print and we could not verify where Rolls had obtained this information from.

So instead we referred to the explorer Giles’ actual 1872-1876 journals, which we believe Mr Pascoe should have done himself.

When arriving at Ooldea (spelt Youldeh in Giles’ journal), Giles makes no mention of a ‘dam’ in his journal. Instead, Ooldea is described as being what is known as a ‘soak’, where some digging through the sand is required to access the water. Giles also makes no mention in his journal of Mr Pascoe’s claim of,

‘for a full week it [the ‘dam’] watered seven men, 22 camels and filled up enough water containers to last them on a dry stage of 500 kilometres’.

Giles also states that there were in fact nine men in the expedition at this stage, not the seven quoted by Mr Pascoe. The actual wording of the relevant excerpt from Giles’ journal (Reference 1) is :

“…there existed a shallow native well in the sandy ground of a small hollow between the red sandhills, and this spot the blacks said was Youldeh [Ooldea]… As there were five whites and four blacks, we had plenty of hands to set about the different tasks which had to be performed. In the first place we had to dig out the old well; this some volunteered to do, while others erected an awning with tarpaulins, got firewood, and otherwise turned the wild and bushy spot into a locality suitable for a white man's encampment. Water was easily procurable at a depth of between three and four feet, and all the animals drank as much as they desired, being watered with canvas buckets; the camels appeared as though they never would be satisfied”.

We undertook a word search of the on-line version of Giles’ journal to locate all the relevant mentions of the word ‘dam’, and we list them as follows:

“When the horses arrived [at the dam], there was only just enough water for all to drink… the dam was extremely poor…”

“…when they turned to the south-west for eighteen miles, finding a small native dam with some water in it…”

“… a lot of fresh native tracks... [led] him to a small native clay-dam on a clay-pan containing a supply of yellow water. This information was, however, qualified by the remark that there was not enough water there for the whole of our mob of camels, although there was plenty for our present number…but the evaporation being so terribly rapid in this country, by the time I could return to Ooldabinna and then get back here, the water would be gone and the dam dry.”

“The dimensions of this singular little dam were very small: the depth was its most satisfactory feature. It was, as all native watering places are, funnel-shaped, and to the bottom of the funnel I could poke a stick about three feet, but a good deal of that depth was mud; the surface was not more than eight feet long, by three feet wide, its shape was elliptical; it was not full when we first saw it, having shrunk at least three feet from its highest water-mark.”

“On the 3rd of September we arrived, and were delighted to find that not only had the dam been replenished, but it was full to overflowing. A little water was actually visible in the lake-bed alongside of it, at the southern end, but it was unfit for drinking.

The little reservoir had now six feet of water in it; there was sufficient for all my expected requirements….The little dam was situated on a piece of clay ground where rain-water from the foot of some of the sandhills could run into the lake; and here the natives had made a clumsy and (ab)original attempt at storing the water, having dug out the tank in the wrong place, at least not in the best position for catching the rain-water.”

And finally, we find a reference to a significant Aboriginal dam, which is the only one in Giles’ journal that comes close to fitting Mr Pascoe’s description. However, in Dark Emu, Pascoe writes, “Giles thought the works as crude…”, but in this case we find that Giles thinks very highly of the dam, so it appears Mr Pascoe is misquoting his source again; or perhaps he just can’t bring himself to accept that Giles has something commendable to say about the Aborigines?

We quote from Giles’ actual journal with sections in bold that appear to correspond to Mr Pascoe’s quote,

“The moon had now risen above the high sandhills that surrounded us, and we soon emerged upon a piece of open ground where there was a large white clay-pan, or bare patch of white clay soil, glistening in the moon's rays, and upon this there appeared an astonishing object—something like the wall of an old house or a ruined chimney. On arriving, we saw that it was a circular wall or dam of clay, nearly five feet high, with a segment open to the south to admit and retain the rain-water that occasionally flows over the flat into this artificial receptacle.

In spite of old Jimmy's asseverations, there was only sufficient water to last one or two days, and what there was, was very thick and whitish-coloured. The six animals being excessively thirsty, the volume of the fluid gradually diminished in the moonlight before our eyes; the camels and horses' legs and noses were all pushing against one another while they drank.

This wall, or dam, constructed by the aboriginals, is the first piece of work of art or usefulness that I had ever seen in all my travels in Australia; and if I had only heard of it, I should seriously have reflected upon the credibility of my informant, because no attempts of skill, or ingenuity, on the part of Australian natives, applied to building, or the storage of water, have previously been met with, and I was very much astonished at beholding one now. This piece of work was two feet thick on the top of the wall, twenty yards in the length of its sweep, and at the bottom, where the water lodged, the embankment was nearly five feet thick. The clay of which this dam was composed had been dug out of the hole in which the water lay, with small native wooden shovels, and piled up to its present dimensions.

Immediately around this singular monument of native industry, there are a few hundred acres of very pretty country, beautifully grassed and ornamented with a few mulga (acacia) trees, standing picturesquely apart…by it I found we had come fifty-eight miles from Youldeh [Ooldea]on a bearing of south 68° east, we being now in latitude 30° 43´ and longitude 132° 44´. There was so little water here that I was unable to remain more than one day, during which the thermometer indicated 104° in the shade.

Reference 1: Various dam-related excerpts from the on-line version of, Australia Twice Traversed by Ernest Giles 1872 -1876.

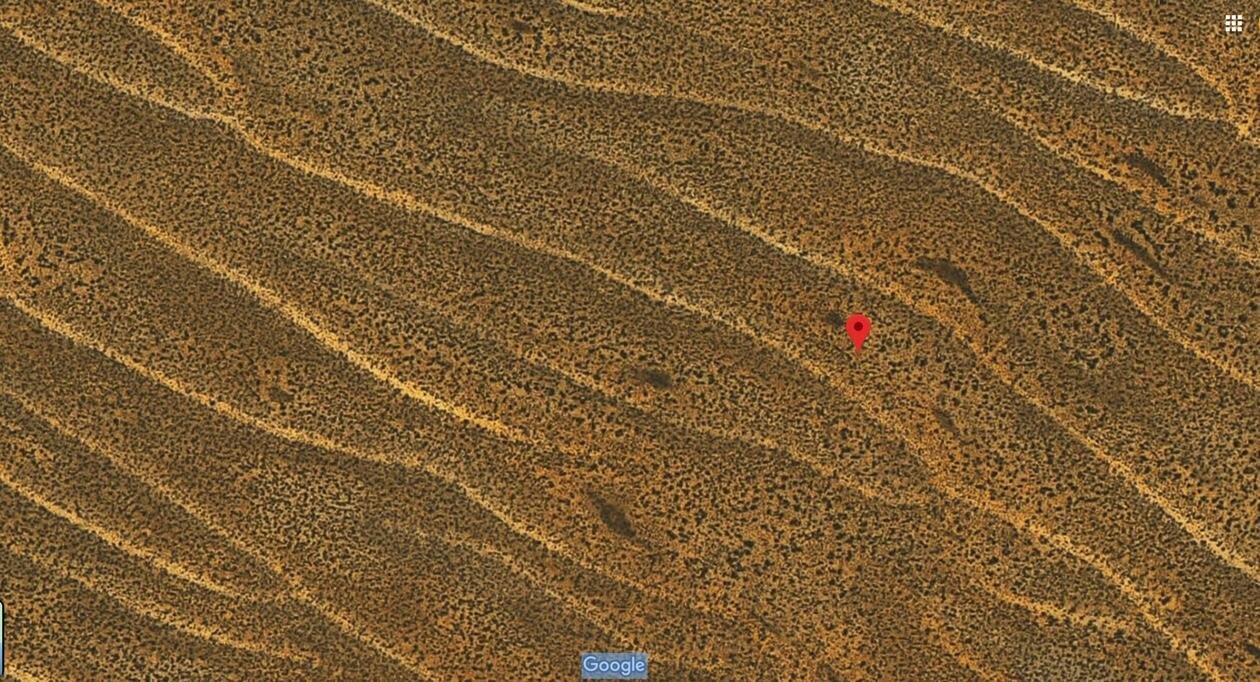

Any sensible reader will appreciate that these descriptions of ‘dams’ in no way constitute ‘evidence’ that the Aborigines were operating ‘irrigation’ schemes to water ‘crops’ as is suggested by Mr Pascoe. In fact, by using Google Maps we can pin-point the actual location of this impressive Aboriginal dam found by Giles as he recorded at, “Latitude 30° 43´ and Longitude 132° 44´”, and see just how inhospitable the country is for irrigation and cropping. This dam described by Mr Pascoe was constructed by the Aborigines purely for collecting precious drinking water, not for irrigation.

Example 2 - Mr Pascoe’s ‘Aboriginal agricultural engineering’

Mr Pascoe writes with regard to what he calls, “outstanding example(s) of Aboriginal agricultural engineering…[that] were seen across the continent” including,

“Norman Tindale saw a dam on the Nicholson River in 1977 that was designed so water would spill over and irrigate the grainfields.” - Dark Emu 2018 Reprint, p46 – Mr Pascoe cites as his reference for this evidence, Tindale, N., Adaptive Significance of the Panara or grass seed culture of Australia in Wright B, [sic] Hunting Gathering and Fishing [sic], AIATSIS Canberra 1978.

This is completely wrong and appears to be a complete distortion of what Tindale actually wrote. Tindale records that he was lead to believe that,

“…the most desirable grasses were most commonly found on mulga plains that became flooded for limited periods after heavy summer rains, and that it was proper [for the Aborigines] to fill the runoff channels of creeks so that the larger areas of ground would be flooded when the rains came. For many years there was no substantiation [that the Aborigines actually did this] but in 1963 a Wanji man from the Nicholson River country indicated that his people knew it was an advantage to get as large an area as possible flooded by these freshets [a ‘freshet’ is a ‘flood of a river from heavy rain or melted snow’] and at certain places where the country was suitable, they choked up the channels with stones, earth and other debris. Areas such as these were well known as grainfields and were visited at the proper times to gather and harvest…[this] suggestion of manipulation of water in the most rudimentary fashion in such areas may be worthy of attention, since it hints at the beginning of agricultural irrigation.” - Tindale, N., Adaptive Significance of the Panara or grass seed culture of Australia, in Wright R.V.S.-Ed., Stone Tools as Cultural Markers, p347.

Mr Pascoe appears to jumble and manipulate Tindale’s commentary to mislead the reader into thinking that a world authority on Aboriginal societies, such as Norman Tindale was, had witnessed first-hand an example of Aboriginal irrigation. In fact, Tindale records this as a one off, second-hand case which he had not witnessed himself but rather, after many years of searching, had been told of it in 1963 (not 1977 as claimed by Mr Pascoe - Note: from about 1970 Tindale had moved to California permanently (See); and we could find no record of Tindale visiting Nicholson River in 1977). This one tribe had a practice of blocking existing channels with stones, earth and other debris (not digging channels or building dams themselves as claimed by Mr Pascoe) so as to divert flood waters onto native grainfields (that is, not fields tilled, planted or cultivated by Aborigines). Tindale did not say that the Aborigines were irrigators, but rather that this practice was intersting and ‘worthy of attention as it ‘hints at the beginning of agricultural irrigation,” which may have developed further in Australia over the next few thousand years (See our blog post of May 12). Tindale always referred to the Aborigines as hunter-gatherers, not agriculturalists (See our blog post of May 30).

We cannot agree with Mr Pascoe that the Aboriginal ‘Indigenous Knowledge’ of ‘choking channels with stones, earth and debris’ is in anyway comparable to modern Australian irrigation engineering.

Example 3 – Mr Pascoe describes another Aboriginal ‘dam’ as evidence for his Aboriginal agricultural irrigation schemes. He writes,

“A dam wall discovered on the Bulloo River floodplain in the Channel Country of south-west Queensland was 100 metres long, two metres high, and six meters at the base; it required 180 cubic metres of material to construct. The clay was mixed with gibber pebbles to create an earthen embankment across the catchment of several streams, and was capable of holding 700,000 litres” - Dark Emu ,2018 Reprint, p46 - cited by Mr Pascoe, from an article by the farmer and writer, Eric Rolls in the out of print Tasmanian, quarterly, literary magazine, Island.

The historian, Geoffrey Blainey describes the exact same Aboriginal dam as follows:

“Water as well as food was occassionaly conserved…A long curved embankment has been recorded on the dry Bulloo River, east of Tinooburra (New South Wales); and if that dam was by Aborigines its embankment would have required the movement of about 115 cubic metres of clay and stones.” - Blainey, G., The Story of Australia’s People – The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia, Viking/Penguin, 2015, p182.

The original investigators and recorders of this Aboriginal dam, R.J & J.M Rowlands, wrote in a peer-reviewed paper,

“The site described here…[t]he Bulloo River Overflow is for periods of up to 10 years or more at a time, a dirt flat clay lake-bed… A slight bank…runs around the hill about 20ft [6m] above the clay lake-bed…on either side of one of the smaller water-courses…[and] which extends for almost 330 ft [100m] in a smooth curve…[this] embankment is up to 20ft [6m] thick at the base…about 2ft [2/3 m] for much of its length and almost 6ft [2m] at the watercourse [overflow]…The material of the bank consists of a mixture of clay and small stones. Earth dug from the hillside beside the bank was mainly clay, the stones being confined chiefly to the surface…evidence suggest that the bank is definitely the remains of an Aboriginal dam, built to retain water for some time after rain. It would provide a reliable supply in this waterless country, and consequently allow convenient hunting in the Overflow area… If this structure is an Aboriginal dam, it is the largest structure built by the Aborigines to be recorded in this country. Its construction would have involved the moving of an estimated 150 cubic yards [115 cubic metres]…It may well have been built over a period of dozens or even hundreds of years, its height gradually being increased to provide a larger storage…[of a] waterhole holding over 150,000 gallons [700,000 litres].” - Rowlands, R.J & J.M, An Aboriginal Dam in Northwestern New South Wales, Mankind, 7 (1969), p 132-136.

Both the Rowlands’, and Blainey (who cites the the Rowlands’ paper), speculate that the dam is Aboriginal, but still couch their conclusions with an “if”, as they have no confirmed proof. Both also described the dam embankment as being designed to form a larger, long-lasting waterhole to retain flood waters. There is no mention of it being constructed for use in irrigation.

This caution is in contrast to Mr Pascoe, who includes the description of this dam under a section in Dark Emu headed, “Irrigation”, which appears to us as another example of his word-play technique of leading the reader to imagine some Aboriginal artefact or practice being grander, or more sophisticated, than it really is. Mr Pascoe’s mathematics is a little rusty too - his cubic yard to metres conversion is wrong : Rowlands’ 150 cubic yards is about 115 cubic metres, not the claimed 180 cubic metres of Mr Pascoe. And we are not really impressed with the volume of the dam - 700,000L sounds like a big number but it is only about 1/4 the size of an Olympic swimming pool - hardly the stuff of a major irrigation scheme for what has been described by the Rowlands’ as, “[i]f this structure is an Aboriginal dam, it is the largest structure built by the Aborigines to be recorded in this country.”

In summary, although Mr Pascoe claims his examples of dams are not “…ambiguous one-off examples. These structures were seen across the continent,” we instead would prefer to rely on the Rowlands’, whose work was partially subsidised by The Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. In a description summary of the Aboriginal dams found in Australia up until that time ( 1969), they write ,

“There are extremely few reports of Aboriginal earth structures used for water storage in the literature available. Giles (1889) reported three clay dams in the Great Victoria Desert of South Australia and Western Australia…Johnston (1941) in a paper summarizing the known Aboriginal waters in northern South Australia, listed several other small Aboriginal dams which have been found in this region since Giles’ expedition. George (1905) also while carrying out geological exploration for the South Australian Department of Mines in 1904, was guided to five small dams. All of these dams in the Great Victoria Desert were constructed in claypans among the sandhills. They appear to have been built across small watercourses or gutters which drain into the clay pans. Basedow (1925) described small banks of clay used to direct rainwater into rockholes, in the Musgrave Ranges, northeast of the Great Victoria Desert. Apart from these examples in northern South Australia, the only other description of an Aboriginal dam known to the authors is by Leichhardt (1847). He described a wall of clay built to catch fresh water from a soakage a little above high water mark, on the bank of a tidal estuary on the Gulf of Carpentaria.” - Rowlands’, ibid

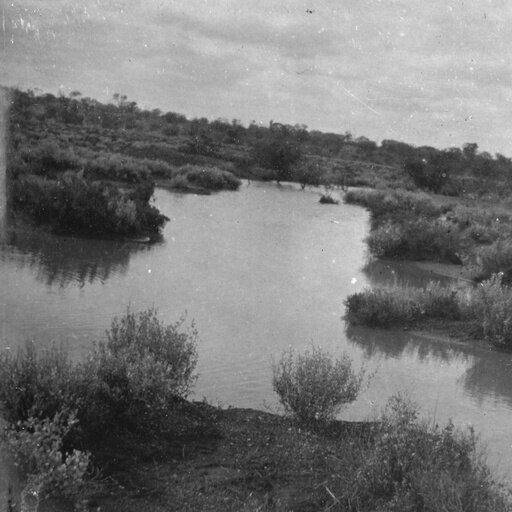

So that is it - hardly the basis for leading the readers of Dark Emu to believe that the Aborigines did build and operate sophisticated irrigation schemes for the irrigation of crops. The most one can conclude is that the Aborigines sometimes created small dams to trap local water flows to provide pools of drinking water, as illustrated in these photographs below.

Photographs from the 1902 Expedition of R T Maurice showing typical Native Dams in South Australia. Photographs from State Library of South Australia