First Contact Part 2 - 'Jump up Whitemen' & Ghosts - European Explorers & Aboriginal Spiritual Beliefs

Many of the First Contacts between European explorers and Aboriginal people were highly dramatic for the Europeans and profoundly spiritual and confronting for the Aborigines who were seeing ‘white’ people for the first time. Although these were often highly tense encounters, they invariably were non-violent.

The Aborigines were often in total shock and bewilderment at encountering a white-skinned, and in particular a white-faced, human who were so far outside the day-to-day Aboriginal frame of reference that these ‘ghosts’ must have come from the spirit world. Indeed, overwhelmingly the Aborigines described these apparitions as returning dead ancestors of their own tribe, who they described variously as, ‘Jump Up Whiteman’ (page 78) , ornya (ghost in Wik Monkan), djanga, or even by the name of a dead relative.

Revisionist history authors such as Mr Pascoe however, always seem to push the narrative that First Contact overwhelmingly ended in violence. The Europeans are portrayed as murderous, trigger-happy invaders who shoot first and ask questions later. Or alternatively they are dumb, lost explorers dying of thirst and hunger in a strange land and are saved from starvation by the Aborigines, who they end up massacring at a later date.

Mr Pascoe never seems to allow for the option that commonly occurred during most of the incidences of First Contacts in Australia - that the Europeans were entering a strange unknown land, peopled by the Aborigines whose customs were alien to them, and the Aborigines were suddenly meeting a strange unknown ‘white being’ entering into their world which, until then, they thought they knew so well. Curiosity and uncertainty held back any violence initially between them and both parties had to quickly adapt thier thinking to cope with the new reality. In the case of the Aborigines, they explained the presence of the Europeans by absorbing these new ‘white-faced beings’ into their spiritual beliefs of re-incarnation.

In this post we will suggest that the Aborigines often initially accommodated these new ‘white-faced’ strangers into their universe as ‘Jump up Whitemen’ - the white returned spirits of their recent deceased ancestors. We will show how '‘white-face’ is commonly used within Aboriginal culture during burial ceremonies and mourning for the dead and how easy it would therefore be to associate real, ‘white-faced’ humans with death, mourning and resurrection. This is not to say that violence did not occur, but just that if it did, it was usually at a much later date, well after First Contact.

To assist us ‘armchair historians’ get a feel for how it may have felt 200 years ago in a First Contact situation between the stone-age Aboriginal people and modern people we have located some examples of film footage of First Contact situations with isolated tribes who have never met people from outside of their own small world.

The first film clip allegedly shows an isolated New Guinea tribe making First Contact with a Belgian film-crew. We are using this film footage as a proxy for what may have happened when Australian Aborigines (NG natives as proxies) first encountered 'white' European explorers (Belgian film-crew as proxies). Although the modern Belgians are clumsy and ill at ease in a strange environment, they can at least comprehend who the stone-age New Guineans are. The New Guineans in contrast, are perfectly at ease in their environment and the universe they know until they are suddenly confronted with strange, new 'white' beings for which they have no explanation for in their universe.

The second film clip we have is from the 1930’s (coupled with some 1980’s commentary and interviews) which shows First Contact encounters between isolated tribes in the Highlands of New Guinea and three ‘white’ Australian gold prospectors travelling with a party of some 90 New Guinean porters. We believe that this footage is an excellent proxy for how Aboriginal tribes (Highland tribes as proxies) may have related to the European explorers (The three Australians as proxies) and their Aboriginal guides (The New Guinean porters as proxies) during the period of First Contact in Colonial Australia.

So to our mind, it is easy to see how Aboriginal people may initially have connected the sudden appearance of a ‘white-faced’ man in their tribal land with a returned, recently deceased member of their tribe, given that the use of white pipe-clay to paint the face and bodies of mourners is widespread amongst Aboriginal tribes.

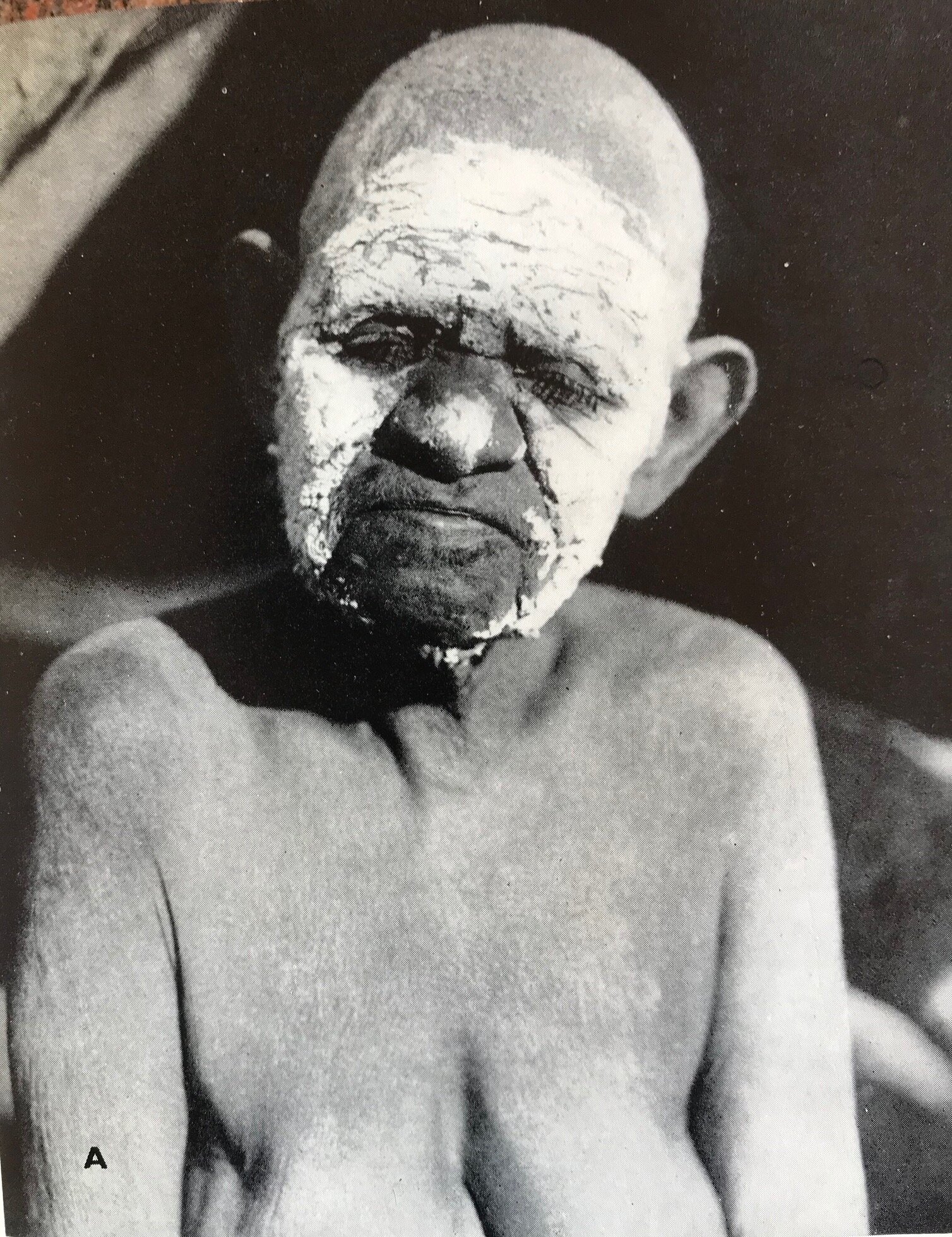

Widow daubed with clay ‘white-face’ mourning loss of her husband - Photo: H. Basedow

Aranda widow with ‘white-face and body’ wearing a tjumurillia head-ornament for a special mourning ceremony called “the trampling of the twigs on the grave.’ - Photo: B. Spencer

In 1901 the anthropologists, Spencer and Gillen, described how mourning Aboriginal women had daubed themselves all over with white pipe clay, and then for three hours they set to work going about in small parties from one camp to another. As they approached the different camps, they lifted up their yam sticks with both hands and then some of the other women would come out and there would be a clashing of yam sticks. Then every woman would prod the pointed end of her stick - which is really a great heavy club - into the top of her head, and then they would all sit down and put their arms round one another and howl and wail like demons.

Mourning women in ‘white-face’ clashing and beating with yam-sticks. Tennant Ck, NT, 1901. Photo : B Spencer

Spencer writes of similar occurences when describing death rites of the Arunta , a central Australian Desert tribe;

“On the way to the grave the…mother often threw herself heavily on the ground and attempted to cut her head with a digging stick…At the grave she threw herself upon it, tearing up the earth with her hands and being literally danced upon by the other women. Then all the other [women ] threw themselves on the grave,…cutting and hitting each other about the body until they were streaming with blood. Each of them carried a digging stick, which was used unsparingly on its owners head and those of the others, no one attempting to ward off the blows which they even invited...In connection with the custom of painting the body [and face] of the mourner with white pipe-clay, there is no idea of concealing from the spirit of the dead person the identity of the mourner; on the other hand, the idea is to render him, or her, more conspicuous, and so allow the spirit to see that it is properly being mourned for.” - Spencer, B., & Gillen, F. J. The Native Tribes of Central Australia, Pub. Macmillan 1938, p 501, 509 & 511.

Wailing women in ‘white-face’ consoling over the death and burial of an Elder man. Tennant Ck, NT, 1901. Photo : B Spencer

These two Wik Monkan children were photographed in 1933 on Cape York Peninsula. They are playing at ornya (ghost). The bark bundle beside the little girl below is a make-believe ‘body’.

Photographic Acknowledgments : D Thomson & Museum of Victoria

Recorded examples where the Aborigines mistook the Europeans for their deceased ancestors - the ‘Jump up Whitemen’

1. William Buckley was an escaped convict, who was found by the Wathaurong Aborigines on the Bellarine Peninsula (Port Phillip Victoria) in 1803 and lived with them for the next 32 years.

William Buckley

James Bonwick in 1856, writes of Buckley’s and other colonists experiences,

‘Buckley's life was saved because he was believed to be the embodied spirit of a deceased friend of the tribe. Mr. Wedge wrote in 1835, " They certainly entertain the idea that after death, they will again exist in the form of white men; … A gentleman of Moonie Ponds told us, that while down in Port Fairy district, an old woman recognized in his little girl a departed daughter of hers.”

In John Morgan’s 1852 narrative, Buckley himself describes his First Contact with the Aborigines in the Geelong area in about 1803,

(from pages 25-35) “One day…I thought I heard the sound of human voices; and in looking up, was somewhat startled at seeing three natives standing off the high land immediately above me…so that hoping I had not been seen, I crept into a crevice in a rock near at hand, where I endeavoured to conceal myself. They were however soon…shouting what I considered to be a call for me to come out,…[and] I crawled from my shelter, and surrendered…They gazed on me with wonder; my size probably attracting their attention. After seizing both my hands, they struck their breasts, and mine also, making at the same time a noise between singing and crying: a sort of whine…”

Buckley, then meets some Aboriginal women who,

“…seizing me by the arms and hands, began beating their breasts and mine, in a manner the others had done. After a short time, they lifted me up, and they made the same sign, giving me to understand by it, that I was in want of food. The women assisted me to talk, the men shouting hideous noises, and tearing their hair…They called me Murrangurk [an Aboriginal name generally used for persons believed to be reincarnated; to have returned from the “sky land”], which I afterwards learnt, was the name of a man formerly belonging to their tribe, who had been buried at the spot where I had found the piece of spear I still carried with me. They have a belief when they die, they go to some place or other, and there are made white men, and they return to this world again for another existence. They think all white people previous to death were belonging to their own tribes, thus returned to life in a different colour… The women were all the time making frightful lamentations and wailing – lacerating their faces in a dreadful manner…They were covered in blood from the wounds they inflicted, having cut their faces and legs into ridges, and burnt the edges with fire-sticks…”

“My presence now seemed to attract general attention [of others in the tribe]; all the tribe, men and women closed up around me, some beating their breasts and heads with their clubs, the women tearing off their own hair by handfuls.”

2. George Grey, the explorer of North West Australia

The explorer George Grey explored North Western and Western Australian between the years 1837-1839. In his journals he notes the discovery of numerous rock-wall paintings showing strange mythical beings with ‘white-face’ (Wandjina). He also records an instance when he was mistaken as a ‘white-faced’, returning, recently deceased member of an Aboriginal tribe. He writes,

“December 4th. We started at sunrise and travelled about six miles in the direction of 17 degrees, and then halted for breakfast at a lake called Boongarrup…The natives [who were our guides on the expedition] here saw the recent signs of strange blacks and…keeping a careful lookout for the friends they expected to see.. at length espied one sitting in the rushes looking for small fish; but no sooner did he see the approaching party than he took to his heels as hard as he could, and two others whom we had not before observed followed his example…Our native comrades now commenced ‘hallooing’ to the fugitives, stating that I had come from the white people to bring them a present of rice and flour…

First one of them advanced, trembling from head to foot, and when I went forward to meet him and shook hands with him it reassured the others, and they also joined our party, yet still not without evident signs of fear. An old man now came up who could not be induced to allow me to approach him, appearing to regard me with a sort of stupid amazement; neither horses or any other of those things which powerfully excited the curiosity of the others had the least charm for him, but his eyes were always fixed on me with a look of eagerness and anxiety which I was unable to account for. We explained to the strange natives that we intended to halt for the night in this neighbourhood, and asked them to show us a good spot with plenty of water and grass…The oldest of the natives, who appeared to regard me with so much curiosity, went off for the purpose of collecting the women, [with]…the strange natives doing their utmost to render themselves useful. They had never before seen white people, and the quickness with which they understood our wants and hastened to gratify them was very satisfactory.

After we had tethered the horses and made ourselves tolerably comfortable we heard loud voices from the hills above us: the effect was fine for they really almost appeared to float in the air…as the wild cries of the women, who knew not our exact position, came by upon the wind…Our guides shouted in return, and gradually the approaching cries came nearer and nearer…I was however wholly unprepared for the scene that was about to take place.

A sort of procession came up, headed by two women down whose cheeks tears were streaming. The eldest of these came up to me and, looking for a moment at me, said, "Gwa, gwa, bundo bal," "Yes, yes, in truth it is him;" and then, throwing her arms round me, cried bitterly, her head resting on my breast; and, although I was totally ignorant of what their meaning was, from mere motives of compassion I offered no resistance to her caresses, however disagreeable they might be, for she was old, ugly, and filthily dirty; the other younger one knelt at my feet, also crying.

At last the old lady, emboldened by my submission, deliberately kissed me on each cheek, just in the manner a French woman would have done; she then cried a little more and, at length relieving me, assured me that I was the ghost of her son who had some time before been killed by a spear-wound in his breast. The younger female was my sister; but she, whether from motives of delicacy or from any imagined backwardness on my part, did not think proper to kiss me. My new mother expressed almost as much delight at my return to my family as my real mother would have done had I been unexpectedly restored to her.

As soon as she left me, my brothers and father (the old man who had previously been so frightened) came up and embraced me after their manner, that is, they threw their arms round my waist, placed their right knee against my right knee, and their breast against my breast, holding me in this way for several minutes… This belief, that white people are the souls of departed blacks, is by no means an uncommon superstition amongst them; they themselves, never having an idea of quitting their own land, cannot imagine others doing it; and thus, when they see white people suddenly appear in their country, and settling themselves down in particular spots, they imagine that they must have formed an attachment for this land in some other state of existence; and hence conclude the settlers were at one period black men, and their own relations.

Likenesses either real or imagined complete the delusion; and from the manner of the old woman I have just alluded to, from her many tears, and from her warm caresses, I feel firmly convinced that she really believed I was her son, whose first thought upon his return to earth had been to re-visit his old mother, and bring her a present... The women, who had retired after having welcomed me, again came in from behind some bushes, where the children all yet remained and, bringing several of them up to me, insisted on my hugging them. The little things screamed and kicked most lustily, being evidently frightened out of their wits; but the men seized on and dragged them up. I took the youngest ones in my arms, and by caresses soon calmed their fears; so that those who were brought afterwards cried to reach me first, instead of crying to be taken away.

Even today amongst Aboriginal people there is a belief in a link between ‘white-face and body’ and the deceased and their spirits.

‘His black skin is painted white as he prepares for his transformation’

"We use white when a person dies, so that's spirit man," Brian Garawirrtja Birrkili, a Gupapuyngu man, says.

An excellent analysis of First Contact, between Aboriginal people and Europeans, is given by Peter Sutton in the book, Strangers on the Shore (Sutton, P. et al Eds.) Nat. Museum of Aust., 2008, p54, where he writes,

Peter Sutton FASSA (born 1946) is an Australian social anthropologist and linguist who has, over a period of almost 50 years (since 1969), contributed to : the recording of Australian Aboriginal languages; the promotingof Australian Aboriginal art; the mapping of Australian Aboriginal cultural landscapes; and increasing society's general understanding of contemporary Australian Aboriginal social structures and systems of land tenure.

‘First encounters with Europeans were arguably experienced by Aboriginal people…it seems, primarily [as] an encounter with relatives who had gone to the spirit world and returned.

One could flee from them, ignore them, get annoyed with them or attack them, without abandoning the view that they were the dead, and one’s own dead.

The dead were always a potentially malevolent and ‘tricky’ group of social beings, as anyone who has camped with traditionally minded Aboriginal people will know. They were family who remained part of one’s real world, even when long ago cremated or buried in body.

One should bear in mind here the matter-of-factness with which Aboriginal people of traditional mind conduct life in an environment richly peopled by the spirits of the dead, by departed people to whom words are regularly said, and whose signs are often seen or heard, especially at night, in the fleshy world.”