'The Sorcerer's Apprentice' - Part 4 : Are Boomerangs Indigenous Drones?

‘Word-Creep’

This blog-post is about the ubiquitous problem of ‘word-creep’ in contemporary Australia - how words, with previously well-defined and understood meanings, are hijacked and manipulated by activists to mean something else, or used to encroach into an area where they don’t belong. It is a very Pascoesque phenomenon beautifully illustrated by the Dark Emu Hoax.

The current area where this is happening is in our school curricula, where all things Indigenous are ‘word-creeping’ their way into our education system under the pretext that Indigenous knowledge is the equivalent of science and the Scientific Method.

It has recently been reported that,

‘…among the members of the advisory group advising the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) on the inclusion of Aboriginal themes in the classroom are activist academics who believe “this country is born of racism” and Indigenous educators who believe the boomerang led to the invention of unmanned drones.’

‘…self-described “Aboriginal mathematician” Chris Matthews. In a series of academic papers written or co-authored by Mr Matthews, he has made the case that the teaching of maths is systematically racist. “Because mathematics education devalues indigenous culture, indigenous students continue to be the most mathematically disadvantaged group in Australia,” he wrote in one'.

‘NSW Aboriginal Education Consultation Group chief Cindy Berwick, also a member of the group, has publicly stated her belief that the boomerang led to the invention of the propeller and flight. Speaking on a special education-themed episode of the ABC’s Q&A in 2018 (here from 05:00), Ms Berwick said: “We actually look at mathematics and science and technology through a cultural lens, and so we actually teach aerodynamics through the boomerang, ‘coz the boomerang actually led to the invention of propellers, which then led to flight, then led to, you know, the invention of drones, which now patrol our coastlines, and save us from sharks…”. However, most experts agree that the principles behind the propeller were discovered by the Ancient Greeks and later refined by 17th and 18th century European inventors’.

- James Morrow in, The Daily Telegraph 31st July, 2021

Despite possibly the best of intentions, the great mistake these Aboriginal educators are making is that they are confusing, or conflating, Indigenous knowledge with science.

There is a wealth of Indigenous knowledge with regards to Australian plants and animals, our land’s seasons and physical environment, and how to survive successfully on this most inhospitable of continents, with nothing more than a simple Aboriginal tool-kit, but coupled with a very complex social and religious infrastructure.

There is no argument for example, that a traditionally-minded Aboriginal man would know more about the type of trees and wood to select to make a boomerang, and how to carve it in such a way that it does the job required of it, than any highly educated, Oxford scientist could hope to know.

But when it comes to the science of the boomerang, the physics of how it actually works and how to describe that, the western-trained scientist or engineer is centuries ahead of any Aboriginal knowledge holder.

As we have explained in a previous blog-post, there is no such thing as Indigenous science - there is only science and the Scientific Method, which does not care at all about the practitioner’s race, ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, sexual preference, supremacy or skin colour.

Boomerang Science

The following paper (below) describes the theory behind how a boomerang works. It is by a Russian mathematician. He may have a boomerang on his desk or in his hand, but presumably he knows little, if anything, about how to select the required tree and the wood; how to carve it; how to sing while carving to ensure the spirits will endow this boomerang with the properties required of it, or how to physically throw it and use it to kill budgerigars. Only a traditionally-minded Aboriginal man can do that - a man that has been initiated into the required Indigenous knowledge.

But the Russian knows many things that the Aborigine cannot know. The Russian can draw on the scientific experience and results of three disparate, scientific studies of the boomerang from across the past 120years (see the papers’ references from, London in 1897, Germany in 1975 and from Asia in 2009), whereas the Aboriginal man can only rely on the training and oral directions from his own parochial tribal teachers - his father, his brothers and his uncles.

In addition, the Russian will be able to vary the parameters of his mathematical formula, such that he can calculate and predict how the boomerang will respond to wide changes in its parameters, such as the angle of throw, the density of the wood, the size and shape of the fins and the prevailing winds. The Russian will even know how the boomerang will perform if it is thrown in the thin atmosphere atop Mt Everest, whereas, the Aborigine will be taken aback if he throws his boomerang while on Mt Everest - the spirits will make the boomerang behave quite unexpectedly, in a way he has never experienced before at sea-level.

The reason for this difference is that the Aboriginal man possesses highly skilled Indigenous knowledge about the boomerang within his world-view, but he does not have the science to be able to describe how the boomerang really works, or how it will perform in unexpected circumstances outside of the parameters of his world view. .

A Scientific Formula to explain how a Boomerang works - Full Paper and references here

With the West’s Scientific Method, and using advanced mathematics and engineering, we can look at a semi-circular piece of carved wood and describe its motion - how and why it flies. An Aboriginal man, although an expert and experienced boomerang maker who can channel thousand's of years of Indigenous knowledge, cannot explain the how, and the why, of the boomerang’s flight, or its returning ability, in anything other than cultural or spiritual terms.

More importantly, the Scientific Method gives modern engineers and scientists the ability, within the span of their own lifetimes, to build on what they have discovered. They can make completely new ‘boomerang-like’ designs such as the Boeing 747 aeroplane wing, drone-propellors, wind-turbines and drag-fins on racing cars. Indeed, this Russian will be using the same mathematics and aerodynamic theories in his calculations on the flight of a boomerang, that he will be using next week on the re-entry trajectory calculations of a Russian space capsule. However, no matter how much Indigenous knowledge the Aboriginal boomerang-carver has, his society did not develop a Scientific Method that would allow him to independently extend his skills to make wind sails, cross-bows, spinning wheels, or kites.

A good example of how Aboriginal society was built on a deep, essentially unchanging knowledge rather than a science is to look at how Indigenous knowledge was controlled by spirituality, or dogma as we would say today.

Dogma is the enemy of science. A society or culture that is governed by a closely controlled, religious dogma may have a high degree of allowable knowledge, but it cannot tolerate the free-thinking and experimental world of science.

Medieval Europe was a time of religious dogma. Inquisitive, free-thinkers, such as Galileo, who started to appear as the Renaissance got underway, could only undertake science and pursue their experiments up to the point where the Church Elders said, enough is enough.

When Galileo championed Copernicus’ scientific theory that the Earth rotated around the Sun, rather than the dogmatic Catholic Church knowledge that required the Sun to move around the Earth, he was investigated and tried by the Roman Inquisition. In 1615, he was found to be "vehemently suspect of heresy", and forced to recant. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

There are numerous examples that support the notion that Aboriginal society worked on the basis of dogma, with unchanging (or exceeding slowly changing) Indigenous knowledge, and not free-thinking experimental science.

Increase Ceremonies or Rituals

Aboriginal societies believed in increase rituals to ensure a steady, plentiful supply of animals and plants for food.

For the continued annual supply of mulga-seeds, one increase ceremony comprised the rubbing of some specific stones while chanting. The ceremony, which needed to be performed at the correct time of the year, released from the totemic stone the relevant life-essence kuranita, which, flying into the air, would cause each specific mulga-tree to bear more seed - (Mountford, C.P., Nomads of the Australian Desert, Publisher Rigby, 1976.)

This is an Indigenous knowledge that we would call a dogma. It is not science. Science tells us that the mulga-tree’s seed-bearing ability is not governed by the rubbing of rocks, but instead by local growing conditions, such as nutrient levels in the soil, the quantity and timing of rainfall, seasonal temperature variations, winds and storms, fire-regimes, plant variety, pest and weed pressure and frequency of cropping.

It is always instructional to refresh one’s understanding of this ‘word-creep’, such as where Indigenous knowledge becomes Indigenous science, by watching this short film clip by Canadian evolutionary psychologist, Gad Saad. He has spent a lot of time thinking about this particular ‘word-creep’ and his views are instructional.

‘A person of a particular racial or ethnic identity does not hold an approach to knowledge that is different to the accepted epistomology of the scientific method. There aren’t multiple ways of knowing’. - Gad Saad, - See here for film clip for his view on ‘indigenous’ science.

A Further Example of the ‘Word-Creep’ - Indigenous Knowledge into Indigenous Science

Joe Sambono is a Jingili man, and zoologist. He is currently a Curriculum Specialist in Science and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education. - Source

One need only read the thoughts of Joe Sambono, a Jingili man and zoologist who is currently a Curriculum Specialist in Science and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education to realise that ‘word-creep’ is well and truely underway.

He is used as an informant on the Australian Museum website, where we can follow Mr Sambono’s literary voyage from his,

‘…love of the scientific method and all the amazing knowledge that exists within Western science’,

to ‘Indigenous science goes well beyond boomerangs and spears’,

then via, ‘This is not an issue of Western science vs Indigenous science’

to arrive at, ‘[Aboriginal] Australia is home to many of the earliest examples of scientific thinking in the world’,

with the final, anti-colonial lament containing the obligatory “R-word”, when those,

‘Western scientists first came to Australia, their ‘best science of the day’ was hugely shaped by racist attitudes and assumptions that have long since been abandoned by all but a few’.

Quotes from Bruce Pascoe and his Dark Emu

‘The science of baking developed alongside the seed harvests’.

‘The science of food preservation and treatment allowed Aboriginal people to render otherwise toxic foods edible. The pandanus and cycad nuts went through stringent sluicing and immersion treatments to remove the poisonously high alkaloid levels’.

- (Ed. Aboriginal people did not use science, but rather developed Indigenous knowledge via “Eat, Die and Learn” )

Bruce Pascoe comparing the relative merits of Australian school kids studying Aboriginal "bread-making" or studying Socrates ( See from 02:50).

Further Reading

The following is an example of how Aboriginal religious and spiritual dogma stifles innovation and the Scientific Method.

Anthropologist Peter Sutton and archaeologist Keryn Walshe in their recent book, Farmers or Hunter-gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate, tells us that Classical Aboriginal societies,

‘were hyper-conservative: change was generally frowned on very seriously, and new ways usually had to be sanctioned by developments in Dreaming mythology, or by introduced sacred ceremonies, or by having been ‘found’ (not created) in dreams and then sanctioned by elders…

Men crossing the Koolatong River, NT, on submerged logs, keeping close together making as much noise as possible to frighten away crocodiles. Source - Donald Thomson, ca 1937

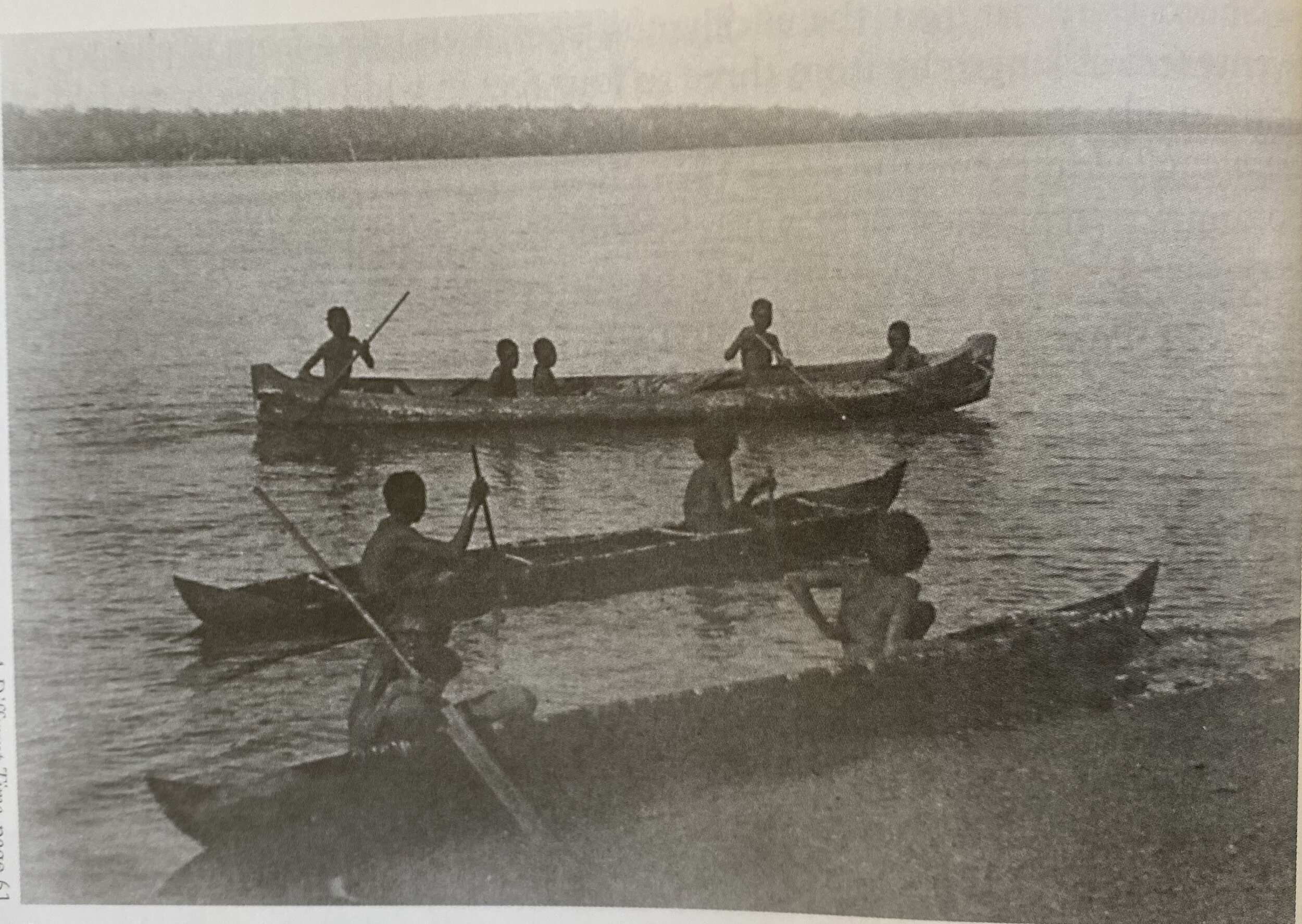

Long canoes used for sea voyages and travelling between islands. The distant one is a dugout cut from a solid tree. The two nearest are made of bark. Melville and Bathurst Islanders, northern Australia. Source - H. Basedow, ca 1911

Dugout canoes along the coast of Arnhem Land were originally obtained by barter or theft from Macassans from about 1720 onwards. Some were fitted out with pandanus fibre sails. This one is known as a lippa lippa - Source Donald Thomson, 1935 : See also Footnotes at end

Women push and pull the bark raft across the river as they swim. NE Arnhem Land, 1937. Source - Donald Thomson

Yir-Yoront people of CYP [Cape York Peninsula], many still living in the bush in the 1930s, made no watercraft. Given that their location was in the wetlands of the Mitchell River system and on the coast, this example stands out as evidence for the role of spiritual traditions in the adoption of technology:

Among the bush Yir Yoront the only means of water transport is a light wood log to which they cling in their constant swimming of rivers, salt creeks, and tidal inlets. These natives know that tribes forty-five miles [72 km] further north have a bark canoe. They know that these northern tribes can thus fish from mid-stream or out at sea, instead of clinging to the river banks and beaches, that they can cross coastal waters infested with crocodiles ...

For them, the adoption of the canoe would not be simply a matter of learning a number of new behavioral skills for its manufacture and use. The adoption would require a much more difficult procedure; the acceptance by the entire society of a myth, either locally developed or borrowed, to explain the presence of the canoe, to associate it with some one or more of the several hundred mythical ancestors ... and thus establish it as an accepted totem of one of the clans ready to be used by the whole community. The Yir Yoront have not made this adjustment, and in this case we can only say that for the time being at least, ideas have won out over very real pressures for technological change.’

- (ibid., p70-71).

To our mind, this is an example of Indigenous knowledge - how to skilfully fashion and use a log as a buoyancy aid, so as to cross a body of water. It is not Indigenous science, because no-one in the Yir Yoront appears to have had the desire or need to ask hypothetical questions and do experimental developments to validate hypotheses such as :

How can I cross the water without being in it?

How can I keep my tool kit dry without having to hold it above my head as I swim?

How can I prevent my wives from being taken by a crocodile, like one was last week, while ferrying my daughters across the estuary on a bark raft?

My neighbours are using dugout canoes and some have adopted a simple canoe sail. What do I need to do to learn how to do that?

Obviously other tribes were able to overcome their Indigenous knowledge and dogma, enabling them to adopt bark canoes, dugouts and sails. However, based on what Sutton and Walshe say, this adoption was most likely due to ‘finding’ a new and acceptable ‘dream’ that allowed the elders to sanction the use of these new watercraft innovations. The Scientific Method was not used at all.

Footnotes

A reader has commented on our caption of this Donald Thomson photograph of a canoe with a sail as follows:

Reader’s submission: “The photo of a sail driven dugout taken in 1935 is then accompanied by the purely speculative caption that aboriginals obtained these vessels through "barter or theft from Maccasans from about 1720".

Is there any actual evidence of this ??

Either of the date or the means ??

What goods did the Palaeolithic society of indigenous Australians have to "barter" with an iron age Indonesian fishing fleet ??

From my limited research these claims seem to stem from activists boasting about things that happened in the distant past without any shred of evidence to support their stories.

These unsubstantiated claims have then been taken as irrevocable proof solely because they are sourced from the unerring pool of indigenous knowledge.

Knowledge that is spiritual rather than scientific. - reader W

To the left are the references we used for this blog post - the original photograph and its caption, and an excerpt of Donald Thomson’s journal from around the same time as his photograph.

Further Notes

a) From the book by D.J.Mulvany, ‘Encounters in Place- Outsiders and Aboriginal Australians 1606-1985 (QUP, 1989) we learn that each of the Macassan praus that came to northern Aboriginal Australia for the annual trepang season,

‘…carried from two to six dugout canoes, used to collect trepang. Aborigines adapted their economy to these seaworthy craft with sails. Sometimes they obtained them through exchange or by savage from wrecked praus, for many wrecks occurred. Theft was common. Later, Aborigines constructed their own canoes, using metal tools.’ - (ibid., p26)

b) From the book, by C.C. MacKnight, The Voyage to Marege - Macassan trepangers in northern Australia,(MUP, 1976)

‘There was little scope in the environment of Arnhem Land for dramatic changes in the economic system of the Aborigines as a result of contact with the Macassans. Cereal agriculture or the manufacture of pottery, two economic traits often accorded some significance, remained foreign drudgery. While the Macassans were still coming, there were many foreign goods to be acquired from them in ways already described, but very few items of material culture were permanently adopted by Aborigines. By far the most important is the dugout canoe together with its sail and other tackle. These canoes, known as lippa-lippa from the Macassarese lepa-lepa, are copied from the simplest type of Macassan craft and the outriggers which were common on the canoes used to gather the trepang have been entirely abandoned. Nonetheless they are superior to bark canoes and permit much more intensive exploitation of the sea's resources than otherwise possible. The first canoes at the Aborigines' disposal were borrowed or stolen from the Macassans, but eventually, probably towards the end oflast century and with the greater availability of metal axes, Aborigines began to make them for themselves’. - (ibid., p90)